The Hazara ethnic group, which makes up around 10% of Afghanistan’s total population, is not only the country’s largest but also the most persecuted.

For vulnerable populations, such as ethnic and religious minorities, the danger of mass atrocities has risen since the Taliban took over Afghanistan in August 2021 with extrajudicial killings, extortion, discriminatory tactics, and forced displacement on the surge.

46 young girls were killed last week in a suicide bomb assault on an educational facility in a Hazara-populated area of Kabul, which drew attention to the persecuted Hazara community in Afghanistan. The bombing took place in the Dasht-e-Barchi neighbourhood of western Kabul, which is home to the minority Hazara minority and is mostly a Shiite Muslim neighbourhood that has been the target of several of Afghanistan’s deadliest attacks.

Following the withdrawal of foreign forces from Afghanistan, persecution against the Hazara community has increased. The Hazaras have a lengthy history of discrimination, especially by the Taliban, therefore they have every reason to fear potential genocide.

Shiite Hazaras in Afghanistan have long endured persecution, with the Taliban being accused of victimising them during their initial control from 1996 to 2001. Additionally, Hazaras are often the subject of atrocities by the Taliban’s adversary, the ISIS affiliate in Afghanistan. Both organizations view Hazaras as heretics.

Afghanistan’s persecuted minority: Who are the Hazaras?

Hazara is Afghanistan’s third-largest ethnic group followed by the Pashtuns and the Tajiks, who make up almost a fifth of the country’s total population. In Afghanistan, which has a Sunni majority, about 10% of Muslims are Shiites, and nearly most of them are Hazaras.

The Hazaras are believed to be of Central Asian and Mongolian ancestry and to be the descendants of the 13th-century Mongolian invader of Afghanistan, Genghis Khan. They are largely based in “Hazaristan,” also known as the homeland of the Hazaras, a hilly region of central Afghanistan. Hazaras are Persian-speaking people who speak a variant of Dari known as Hazaragi.

The Hazaras are disdained by the Taliban because they belong to a different sect and have different ethnic origins; as a consequence, they are regarded as “infidels” by the Taliban. The Hazaras are regarded as a sworn enemy by the Taliban and other Sunni extremists, most especially Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISIS-KP), partly due to their practice of Shi’a Islam.

The Taliban has had a history of execution and repression of minorities and rendered attempts to enforce their idealised version of Islamic “purity” through their stringent regulations and often violates the human rights of the persecuted minorities.

https://www.hrw.org/legacy/pubweb/Webcat-03.htm

The Hazara people, one of Afghanistan’s largest ethnic groups, have been subjected to numerous forms of persecution by Pashtun rulers and regimes, including enslavement, systematic eviction from ancestral residences and territories, and massacres. Some individuals believe Hazaras to be among the “most persecuted community members in the world” as a result of their experiences.

The community has historically been one of the poorest in Afghanistan and experiences daily abuse, including difficulty getting employment. Women and ethnic minority groups, including the Hazaras, suffered the most Taliban torture after the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan in 1996.

Afghanistan: Long History of persecution and systematic genocide of the Hazaras

Hazara people have long been persecuted in Afghanistan; the first incidence of their persecution is from the early 20th century, when Abdul Rahman Khan, the country’s founder, compelled them to flee or perish. When the Taliban seized Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998, they initiated a door-to-door operation to massacre male Hazara members, including young children, and rape or kidnap the women to eradicate them from Afghan society.

According to estimates, ethnic cleansing caused Hazarajat to lose about 60% of its population; as a result, some historians have labelled the atrocity a genocide. Hazaras suffered repression, prejudice, and socioeconomic marginalisation throughout the past decades. The crisis is exacerbated when politics of religion, identity, power, ethnicity, and socioeconomic positioning interest, making it difficult for the marginalised Hazaras to escape the wrath of being embodied as an outcast in Afghan society.

Shiite Hazaras in Afghanistan have endured persecution for extended period of time and the Taliban is accused for mistreating them during their initial control from 1996 to 2001. With the Taliban’s return to power in 2021, these attacks and brutalities have begun to resurface.

Since 2015, an even deadlier wave of attacks against the Hazara population has been unleashed by the rise of the even more extremist Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), with suicide bombers attacking schools, mosques, and perhaps even healthcare facilities in Hazara neighbourhoods.

“These violent deaths are further shocking proof that the Taliban continue to persecute, torture and extrajudicially execute Hazara people.”

-Agnès Callamard, Amnesty International’s Secretary General

Reports of widespread “evictions” of Hazara community from their ancestral residences and properties in Daykundi region surfaced in Western media in late September and mid October of 2021. As a cold winter approached, Taliban militants expelled nearly 4,000 Hazaras from their houses on the grounds that they had no legal claim to the property, leaving them trapped without food or shelter. A regional Taliban court in Mazar-e-Sharif made the decision to evict about 2,000 households, again on the grounds that they were not the owners of their properties.

The Dasht-e-Barchi area has been ravaged by numerous attacks, many of which targeted women, kids, and schools. Before the Taliban regained control of the country last year, three bombs exploded nearby their school, killing at least 85 people, mostly female students, and wounding approximately 300 others.

25 people, which include the new mothers, were killed in a brutal gun assault on a maternity facility of a health centre in Dasht-e-Barchi in May 2020. Additionally, two deadly bomb explosions in April of this year at two different educational facilities in the neighbourhood left at least 20 people injured.

The Taliban have carried out targeted attacks and forced thousands of Hazara residents to flee their homes despite promises that they would safeguard the Hazaras from threats. The Hazaras may be at risk of imminent ethnic cleansing as there is now a definite pattern of Taliban offences being committed throughout Afghanistan.

In face of state repression and continual persecution, the Hazara minority prevails in presenting a two-fold threat to the oppressive forces. By continuing to assert their religious truth and their existence being evidence of a native, pluralistic tradition of Islam that accepts different religions, as opposed to the idealist and puristic views of the Taliban.

An investigation into the plight of Hazara in Pakistan and Afghanistan started by the British Parliamen t stat that Hazara face a high risk of genocide due to the atrocities of IS-K and the Taliban as an ethnic and religious minority.

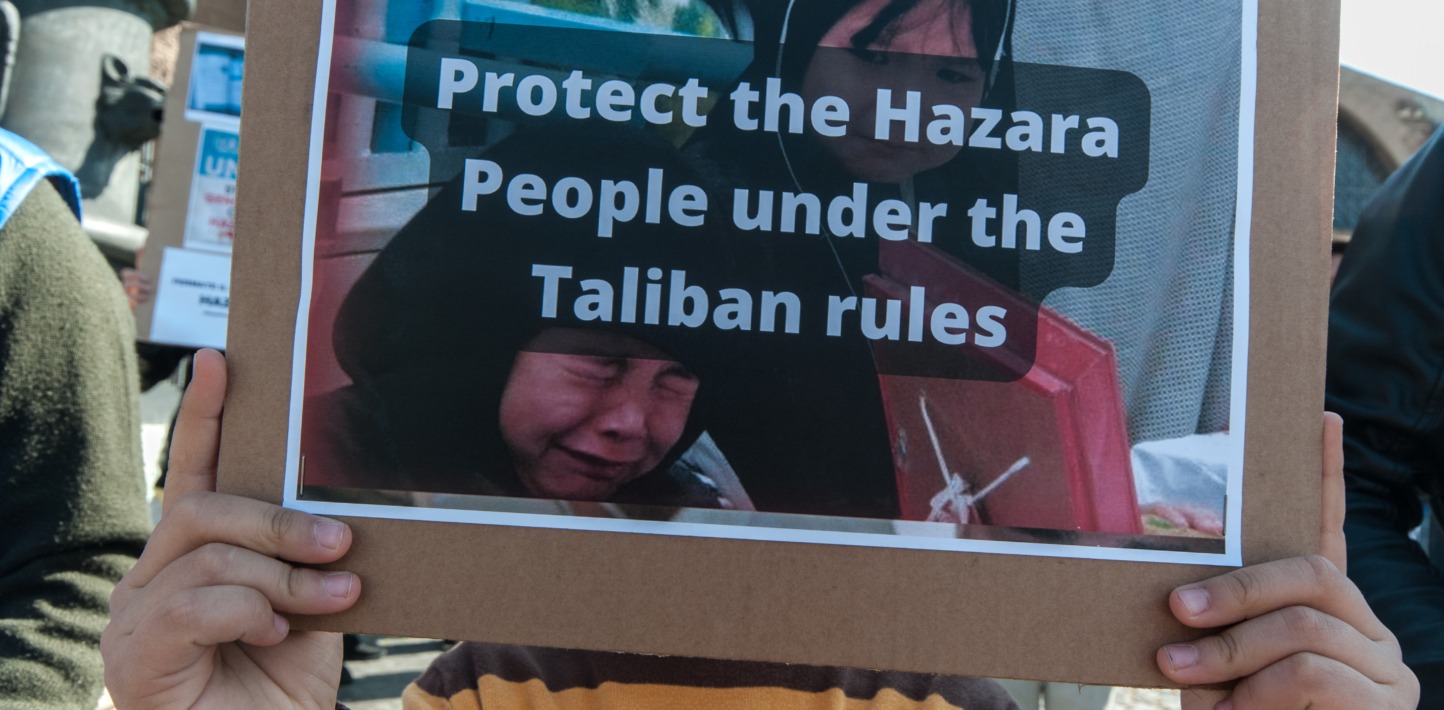

These targeted killings are proof that ethnic and religious minorities remain at particular risk under Taliban rule in Afghanistan.

Agnès Callamard, Secretary General of the Amnesty International

With an endless power tussle in the backdrop of a long-standing history of ethno-nationalist conflict, the Taliban’s effort to curb the increasing dissenting voices of the Hazaras is an indication of the Taliban’s strict doctrine of intolerance. The vision of Afghanistan as a multi-ethnic and pluralistic nation is under serious threat, with religious and ethnic minorities repeatedly encountering persecution and expulsion.

All Afghans continue living in poor and perilous circumstances, but the Hazara community are in an especially severe position since they have historically been marginalised, displaced, and persecuted. International human rights organisations can act to address the threat of ethnic cleansing and perhaps even genocide that these people confront.

Numerous Hazara women violated a prohibition on demonstrations on Saturday to condemn the most recent casualties in their community. Around 50 ladies marched passed a clinic in Dasht-i-Barchi where numerous attack victims were being treated while chanting, “Stop Hazara genocide, it’s not a crime to be a Shia.”

The demonstrators carried signs that said, “Stop killing Hazaras,” and they were clad in black hijabs and headscarves.

As the Hazaras continue to face persecution and brutal force, there needs to be a global effort to protect the community to avert an impending genocide, the signs of which have already started to unveil.