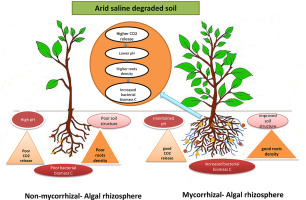

Climate change mitigation is greatly aided by grazing animals as it affects the amount and stability of a sizable soil carbon store, “grazing by mammalian herbivores can be a climate mitigation technique,” the paper explains. In graze-free regions, soil carbon levels varied by 30–40%. While it was more stable where the huge beasts continued to graze. Large mammalian herbivore conservation in grazing habitats is still important because soil stores more carbon than all plants and the air combined.

In a nutshell, grazing animals are a powerful tool in the fight against climate change

Removing herbivores from grazing habitats in the Spiti region of the Himalayas through experimentation has been shown to increase soil carbon level oscillations, which may have unforeseen negative repercussions for the global carbon cycle.

Grazing habitats, such as the Spiti region in the Himalayas, rely heavily on the contributions of large animal herbivores like the yak and ibex to maintain a stable stock of soil carbon. In graze-free regions, soil carbon levels varied by 30–40%. While it was more stable where the huge beasts continued to graze. Rapid soil carbon loss due to improper grazing management is not readily recouped.

Source: Kercentre

Source: Kercentre

More carbon in soil than in all plants in the air to plug the Climate Change

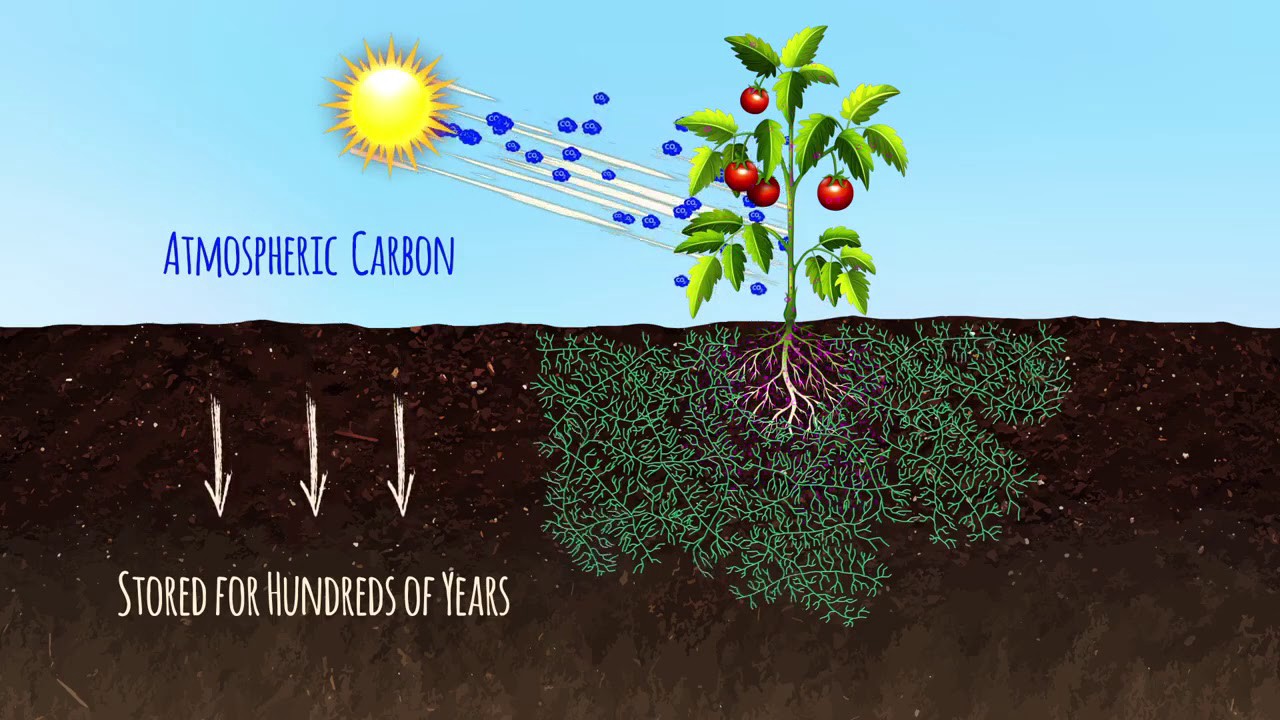

About 25% of annual global fossil fuel emissions are currently removed by soils. Permafrost and peat are the primary forms of soil carbon storage in the Arctic and other wet regions, such as the boreal forests of Northern Eurasia and North America. Less carbon is stored in hot, dry soils. Consequently, making sure it lasts is crucial. Dead organic matter from plants and animals stays in the soil for a long time before being decomposed by bacteria and releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Carbon is effectively sequestered in the soil pool.

Source: Logan Hailey

Source: Logan Hailey

As a result, mitigating the effects of climate change requires steady amounts of carbon in the soil. For the simple reason that grazing ecosystems account for roughly 40% of the planet’s total land area. Approximately one-third of the world’s soil carbon is located in these ecosystems, which include grasslands, savannas, and shrub steppes. Soil carbon storage has the potential to be a significant source of carbon sinks in these ecosystems. Therefore, safeguarding herbivores that maintain stable soil carbon levels should continue to be a high priority for climate change adaptation.

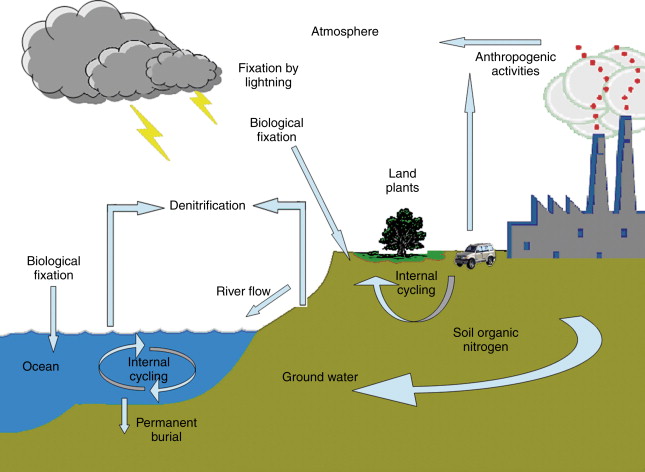

A key factor in fluctuations in carbon level in soil is nitrogen.

Nitrogen’s effect on the soil’s carbon pool can be either stabilising or destabilising. But the interactions between them are tipped in favour of the former due to the effects of herbivore grazing.

Source: Science Direct

Source: Science Direct

The amount of carbon that soils can absorb and store for a given period of time varies by location and is mostly affected by how the land is maintained. Actually, soils have lost 50–70% of the carbon they previously stored due to the fact that approximately half of the area capable of supporting plant life on Earth has been transformed to croplands, pastures, and rangelands. About a quarter of all the greenhouse gas emissions that have warmed the globe are attributable to this.

To put it simply, the carbon in the soil is released into the atmosphere when agricultural operations like tilling, planting mono-crops, removing crop leftovers, using excessive amounts of fertilisers and pesticides, and overgrazing are carried out. Soils release carbon when forests are cut down, permafrost is thawed, or peatlands are drained.

Changes in soil carbon to tackle climate change

Soil carbon was shown to fluctuate by 30–40% higher between years in the enclosed plots when animals were absent compared to the grazed plots, where it remained more consistent. Nitrogen was an important driving force behind these shifts. Nitrogen’s effect on the soil’s carbon pool can be either stabilising or destabilising. However, the researchers observed that grazing by herbivores modifies their interactions in ways that tip the scales in favour of the former, as reported by IISc.

Source: Science Direct

Source: Science Direct

Previous research has assumed that carbon accumulation or loss is a sluggish process, thus scientists have focused on detecting carbon and nitrogen levels over extended time periods. However, the interannual oscillations they observed in their data present a totally different picture. According to Dilip GT Naidu, a PhD student at DCCC and the study’s first author, these changes can have significant climatic consequences because they are linked to the ways in which large mammalian herbivores affect soil.

The researchers concluded that preserving herbivores who maintain stable soil carbon should continue to be a top priority in the fight against climate change, as grazing ecosystems account for roughly 40% of the Earth’s land surface