A group of cryo-engineers and surgeons at the University of Minnesota has developed a technique for cryogenically freezing and thawing rat organs while maintaining their viability. The team used their novel technique in their study published in the journal Nature Communications to solve earlier issues with freezing organs.

Organ Transplantation Scenario

The first successful organ transplant was performed by Boston surgeons in 1954 when they put a healthy kidney donated by 23-year-old Ronald Herrick into the body of his twin brother Richard, who had passed away from renal disease.

Since then, more than a million organ transplants have been carried out in the US. Owing to remarkable improvements in surgical methods, immunosuppressive, and other areas, the great majority of organ transplants done today are successful and extend the recipient’s life by several years.

Sadly, not everyone who needs a new organ receives one; in the US, 17 individuals on the waiting list pass away every day because they did not receive a transplant in time.

Major Roadblock in Organ Transplantation

There is just a very little window of time between donor and receiver during which they are still viable. The longest survival period for any major organ is 48 hours for kidneys, whereas hearts and lungs must be transplanted within 4 hours following removal. As a result, countless organs are wasted even though there are ever-growing waitlists for them. While freezing organs can extend their shelf lives, the tissue can be damaged by ice crystals that grow between the cells, making many of them unusable.

In the 1980s, researchers found that treating human eggs with “cryoprotectants” before rapidly freezing them in liquid nitrogen prevented ice crystals from developing during the process of cryopreserving human eggs. This induces a glass-like condition without ice crystal formation. The heated eggs might then be utilized for IVF in the future.

Organ preservation using vitrification has recently received great research interest. However, defrosting organs without harming them is difficult since existing rewarming techniques begin at the surface and provide uneven warmth. Areas of the tissue warm up at varying speeds causing tears and cracks.

Breakthrough in Cryo-freezing Organs

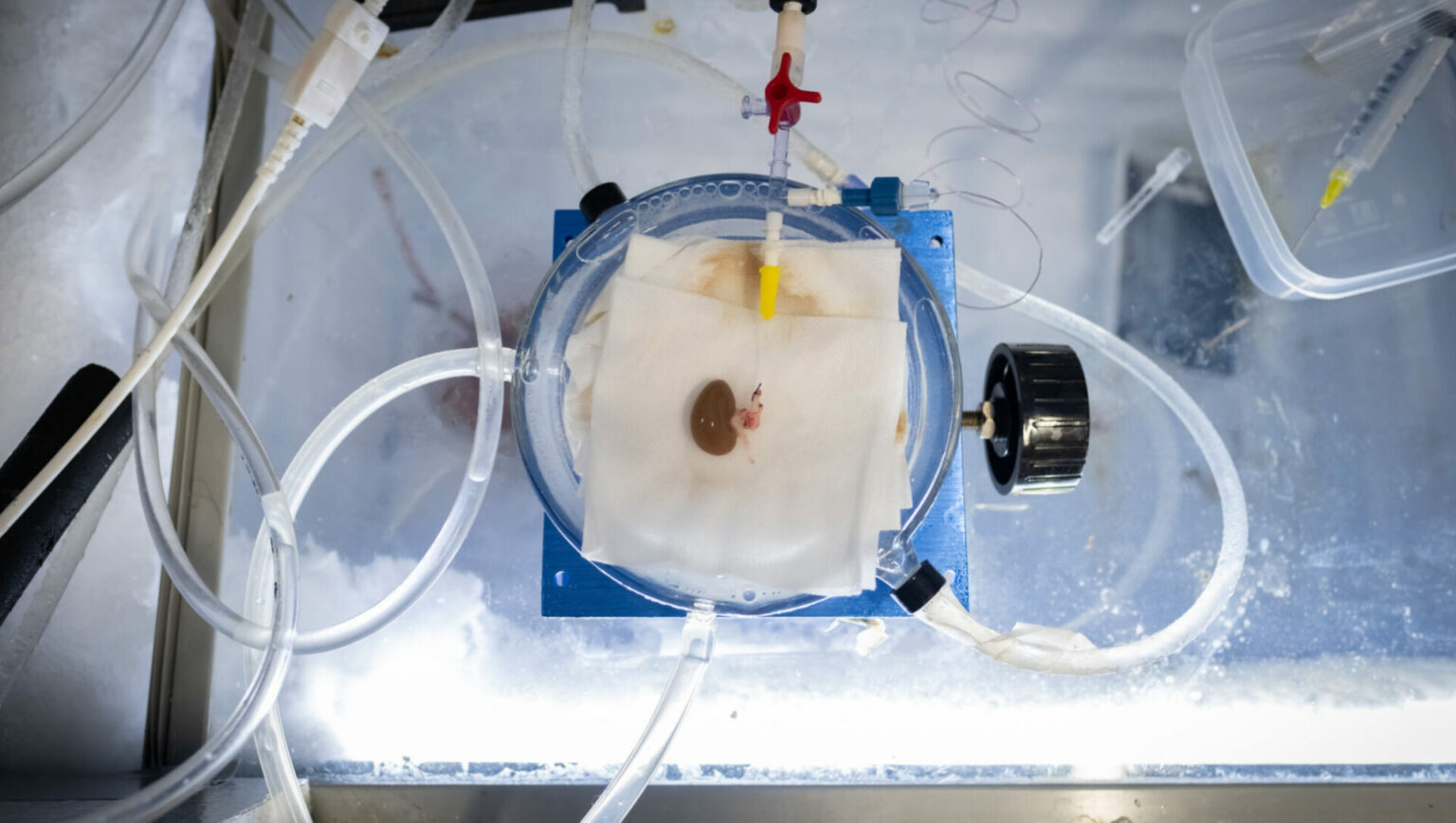

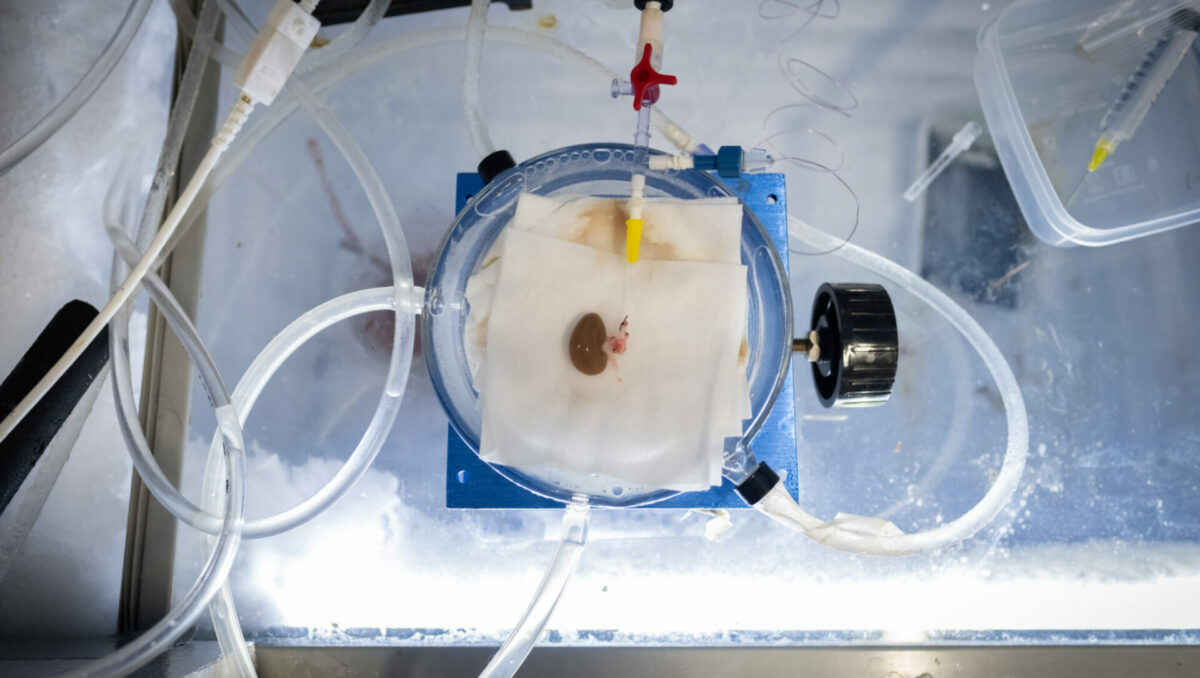

The UMN team claims that they have discovered a solution to this issue. They infused a cryoprotectant solution with iron oxide nanoparticles into the blood arteries of rat kidneys as part of their work. The organs were then preserved for up to 100 days after being chilled to -122 °C (-187.6 °F).

When the cryogenically frozen organs needed to be thawed, the scientists put them in a copper coil and used electricity to produce a magnetic field around them. The iron nanoparticles inside the kidneys heated up as a result of the magnetic field, equally heating the organs in just 90 seconds. Following this “nanoheating,” the researchers removed the kidneys’ cryoprotectant and nanoparticles before transplanting them into five rats.

The kidneys were not fully functioning for the first two to three weeks, but they recovered after three weeks, according to co-author Erik Finger. They were completely functioning kidneys that could not be distinguished from newly transplanted organs after a month.

Looking forward

The cryogenically frozen organs did not immediately function as well as fresh kidneys; instead of starting to produce urine in a matter of minutes as one might anticipate from a kidney that has not undergone vitrification, the cryogenically frozen organs required 45 minutes.

The fact that they finally began to function normally is encouraging, but because all of the rats were euthanized for examination 30 days after surgery, it is unknown if they would have the same lifetime as conventional donor kidneys.

The most important point to keep in mind before being too hopeful is that the outcomes of rodent studies frequently do not generalize to humans. However, according to the UMN researches, there is “no physical reason” why their method of nanoheating wouldn’t be effective on bigger cryogenically frozen organs. They are now testing on pig kidneys, and within a year or two, they may be testing on human organs as well.

Five years from now, clinical studies that actually transplant organs into humans might begin, according to the experts.