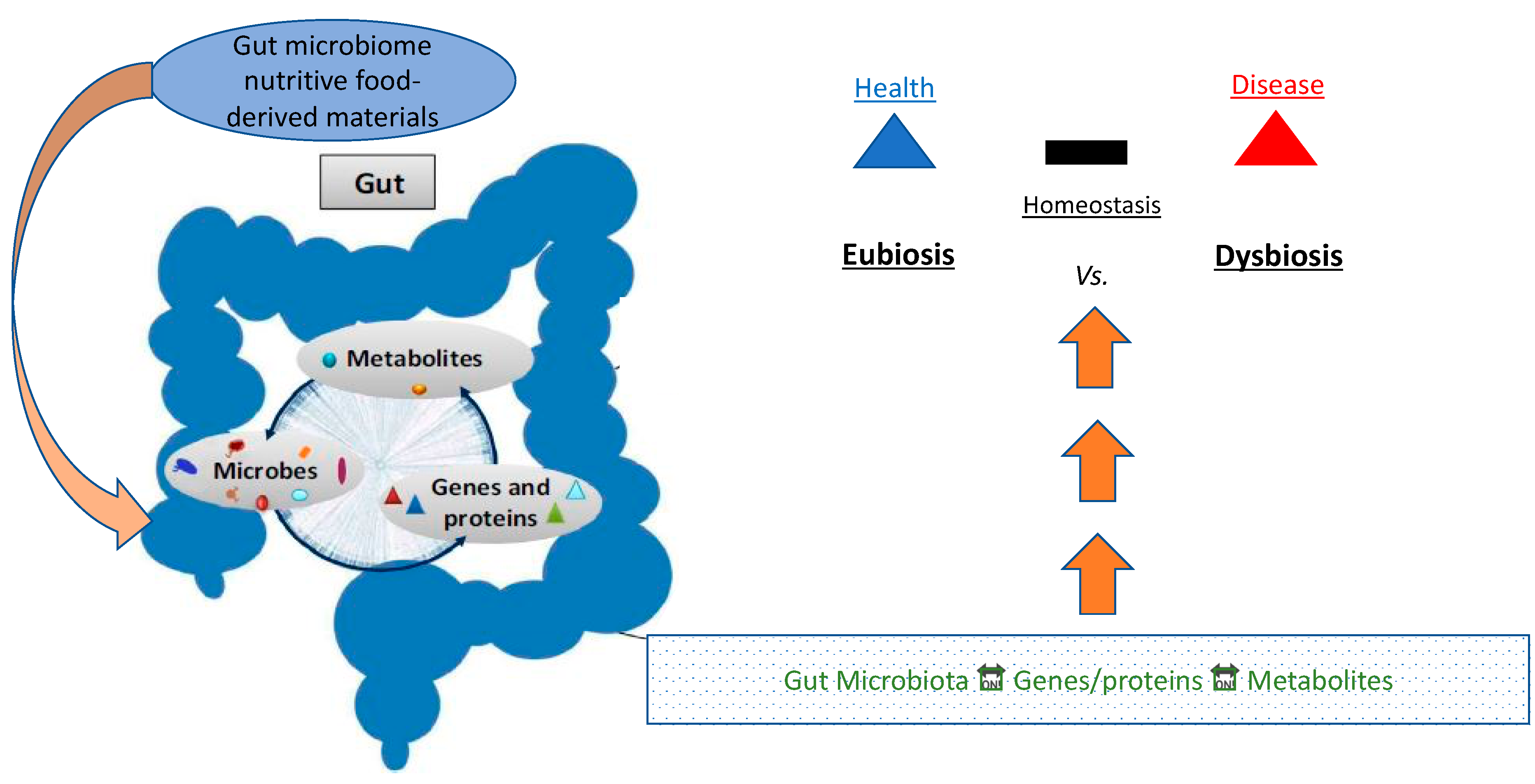

There is a lot of information supporting the connection between metabolic disorders like diabetes and gut microbiota.

There is evidence to suggest that gut bacteria may play a role in the development of diabetes. Some studies have found that people with diabetes have different types and numbers of gut bacteria compared to people who do not have diabetes. The specific role that gut bacteria play in the development of diabetes is not yet fully understood, but it is thought that they may affect how the body processes glucose and how well insulin works in the body.

One type of gut bacteria may promote the onset of Type 2 diabetes, but another type may protect against it, according to preliminary results from an ongoing prospective experiment conducted by Cedars-Sinai researchers.

Gut-Bacteria and Diabetes

A study that was published in the peer-reviewed journal Diabetes found that individuals with higher levels of the bacterium Coprococcus in their microbiomes tended to have higher insulin sensitivity, while individuals with higher levels of the bacterium Flavonifractor in their microbiomes tended to have lower insulin sensitivity. Additionally, studies have shown that individuals with improper insulin processing have fewer numbers of a particular type of bacteria that generates a fatty acid called butyrate.

An ongoing investigation of patients at risk for diabetes is being led by Mark Goodarzi, MD, Ph.D., head of the Endocrine Genetics Laboratory at Cedars-Sinai, to determine if those with lower levels of these bacteria go on to acquire the condition.

“The main question that has to be addressed is whether diabetes caused the alterations in the microbiome or if the variations in the microbiota caused diabetes.” Goodarzi, the study’s main author and the head of the multidisciplinary Microbiome and Insulin Longitudinal Evaluation Study, said (MILES).

Since 2018, MILES researchers have been gathering data from participating non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White persons between the ages of 40 and 80. An earlier cohort analysis from the MILES experiment found a greater incidence of prediabetes and diabetes in children born through cesarean section.

Researchers reviewed data from 352 individuals without known diabetes who were included in the current experiment and recruited from the Wake Forest Baptist Health System in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Procedure

Participants in the study were required to attend three clinic sessions and gather stool samples ahead of time. Data gathered on the initial visit was examined by the investigators. To analyze the patients’ microbiomes and especially seek for bacteria that previous studies have revealed to be related to insulin resistance, they performed genetic sequencing on the stool samples, for instance. Additionally, each participant completed a diet questionnaire and underwent an oral glucose tolerance test to assess their body’s capacity to digest glucose.

Research Findings

Researchers discovered that 28 patients had oral glucose tolerance tests that indicated they had diabetes. Additionally, they discovered that 135 individuals had prediabetes, a condition in which an individual’s blood sugar levels are higher than usual but not high enough to be classified as diabetic.

The study team looked at correlations between 36 butyrate-producing bacteria discovered in stool samples and a person’s capacity to keep insulin levels within normal range. They took into account variables including age, sex, body mass index, and race which can also increase a person’s chance of developing diabetes. An interconnected network of bacteria, including Coprococcus and related microorganisms, improved insulin sensitivity. Flavonifractor, although producing butyrate, was linked to insulin resistance; earlier research by others discovered increased quantities of Flavonifractor in the stools of diabetics.

Researchers are still examining samples taken from study participants to understand more about how the microbiota and insulin production evolve over time. They also intend to investigate the potential impact of nutrition on the microbiome’s bacterial balance.

However, Goodarzi stressed that it is still too early to determine how people might alter their microbiome to lower their chance of developing diabetes.

Goodarzi, who holds the Eris M. Field Chair in Diabetes Research at Cedars-Sinai, stated that the concept of taking probiotics “would truly be rather experimental.” “More study is needed to pinpoint the precise bacteria that must be regulated to prevent or treat diabetes, but it will happen, possibly within the next five to ten years,” he added.