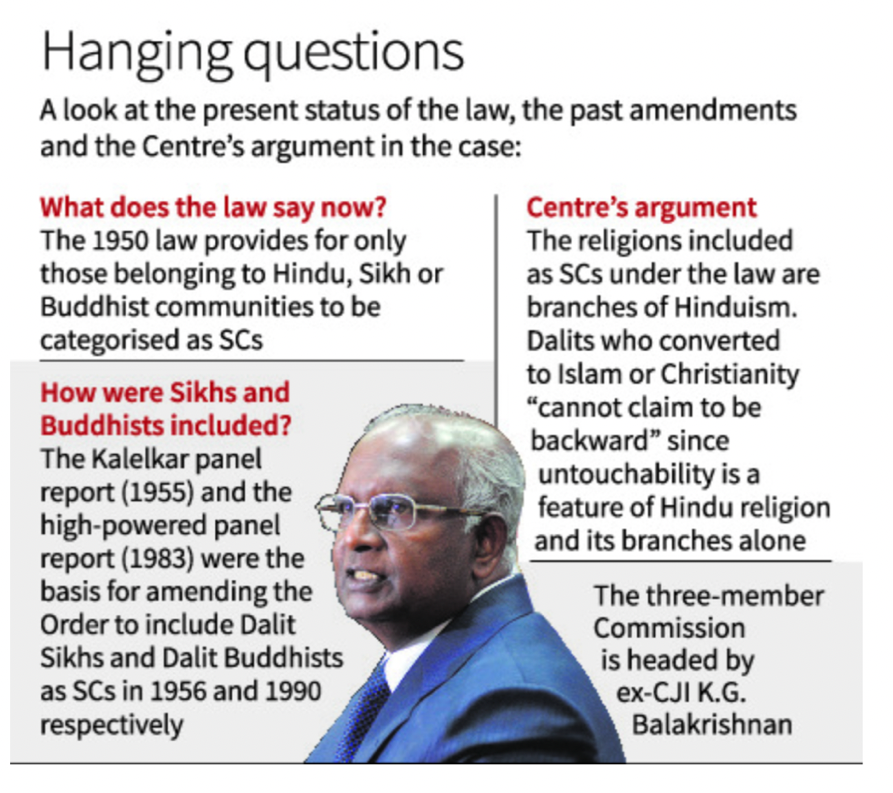

The Union government has appointed Justice K.G. Balakrishnan, the former Chief Justice of India, headed a three-person Commission of Inquiry to determine whether Dalits who have converted to religions other than Sikhism and Buddhism should be granted SC status. Two years have been set as the deadline for the Commission’s report. Let’s trace the history of how Scheduled Caste eventually came to include Dalit Muslims and Christians.

At this time, the Supreme Court is also considering the case (SC)

Prior efforts to classify Sikhs and Buddhists as SC

The first such edict was issued in 1950, and it applied solely to Hindus at the time.

However, Sikhs of Dalit heritage were included in the SC quota in 1956 after repeated requests from the Sikh community.

Following a similar request by Buddhists of Dalit descent in 1990, the government issued a new ordinance that read: “No person who professes a religion different from the Hindu, the Sikh or the Buddhist religion shall be deemed to be a member of Scheduled Caste.”

Afterward, SC welcomed Christians and Muslims

In the years following the 1990s, a number of Private Member’s Bills were introduced in Parliament to accomplish this. The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Orders (Amendment) Bill was written by the government in 1996, but it was never submitted in Parliament due to differences of opinion.

Both the Ranganath Misra Commission and the Rajinder Sachar Commission were established during the tenure of the UPA Government (PM Manmohan Singh).

Ranganath Misra Commission (2004): The Ranganath Misra Commission is also known as the National Commission for Religious and Linguistic Minorities.

It advocated a ten percent quota for Muslims and a five percent quota for other minorities in government positions, and it favoured Scheduled Caste designation for Dalits across faiths.

It also suggested doing away with the Scheduled Caste Order from 1950, which still discriminates against , and decoupling Scheduled Caste identity from religion.

Rajinder Sachar Commission (2005): In March 2005, a seven-member committee led by former Delhi High Court Chief Justice Rajinder Sachar studied Muslims’ social, economic, and educational conditions.

It pushed the subject of Muslim disparity to the forefront and advocated creating an Equal Opportunity Commission to handle discrimination complaints, including housing.

Create a nomination process to boost minority participation. Delimit constituencies without reserving them for SCs. Accept madarsa degrees for military, civil, and banking exams.

Source: The Indian Express

Submission of Current Petition to the Supreme Court, 2022

Some petitions seek quota advantages for Christians and Muslims of Dalit heritage based on the Ranganath Misra Commission.

In the last hearing on August 30, Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul handed Solicitor General Tushar Mehta three weeks to explain the Union government’s position.

On October 11, the administration will likely notify the court of the Justice Balakrishnan panel.

Source: HT

Source: HT

Balakrishnan commitee 2022: Ex-CJI K.G. Balakrishnan will lead a three-member commission with a two-year deadline.

The three-member committee will also include UGC member Professor Sushma Yadav and former IAS officer Ravinder Kumar Jain. It has two years from the day Justice Balakrishnan assumes charge to produce a report.

The government has formed a committee to study whether Dalits who have converted to religions other than Sikhism or Buddhism may receive Scheduled Caste status.

The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950, defines SC as Hindu, Sikh, or Buddhist.

The government has formed an investigation committee to determine if Dalits who have converted to Islam or Christianity may be given SC status.

Source: The Quint

Because of the social handicaps and prejudice they experienced as a result of untouchability, only Hindu groups were permitted to be designated as SCs when the Order was implemented. In 1956, it was revised to recognise Sikh communities as SCs, and in 1990, it was revised again to recognise Buddhist groups as SCs.

The Department of Social Justice and Empowerment states that the commission’s investigation would also include the effects of religious conversion on a person’s status as a Scheduled Caste individual.

What Now?

The Balakrishnan Committee has been granted two years to complete its findings, therefore this process is ongoing. We should hold off until the Supreme Court issues an order, which might hasten the Commission’s suggestions and will decide what is there for muslims and dalits in the supreme court’s basket.