During the two-day G20 cybersecurity summit, the topic of India’s frequent internet outages was raised. One of the panellists, Nneena Nwakanma, stated that India should cease shutting down the internet at any moment.

She participated in a panel discussion on Internet Governance-National Responsibility and Global Commons alongside other participants. The International Digital Health and AI Research Collaborative, with which Nwakanma is affiliated, frequently imposes net limits. Nwakanma was responding to these restrictions.

On the first day of the conference, Nwakanma said, “I haven’t seen any case of internet shutdowns being brought before Parliament, nor is there any empirical evidence of economic returns (by imposing bans).”

However, if law enforcement officials must impose a ban, they must do so following the law, and their elected representatives should be able to justify such decisions to their constituents. When nations attempt to establish internet governance, internet bans pose one of the biggest threats to public trust.

The most recent internet censorship in India was implemented in the state of Manipur, where it has been stopped since May 3 for 71 days until July 20. The Manipur government’s appeal against the Manipur High Court’s order for a limited restoration of the internet is set to be heard by the Supreme Court on Monday.

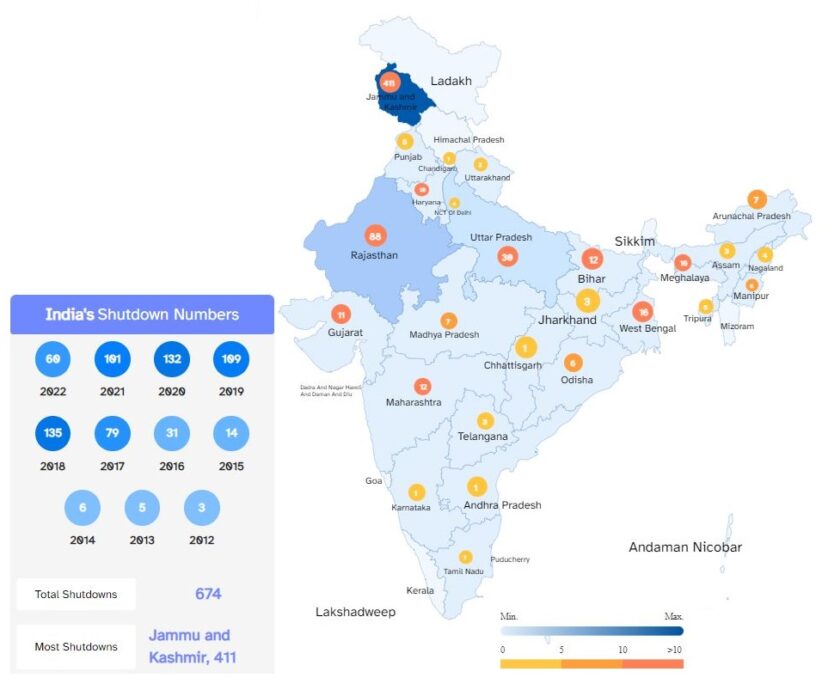

Previously, during the crackdown on the pro-Khalistan leader and Waris De Punjab chief Patrol Amritpal Singh, the internet was shut down in the border state of Punjab in March of this year. Before that, Jammu and Kashmir experienced the longest internet blackout following the repeal of Article 370 in August 2019.

Among the 80 shutdowns that occurred in 21 nations during the same period, India imposed the most shutdowns, at least 33 up until May 2024, according to international digital rights organization Access Now.

According to a study by Access Now, in addition to India, other nations that enacted bans included China, Brazil, Cuba, Ethiopia, Guinea, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Myanmar, Oman, Pakistan, Russia, and Turkey.

Rajiv Jain, a former head of the Intelligence Bureau and a member of the National Human Rights Commission, responded to a question about the frequent internet restrictions in India by stating that the rights to freedom of expression, privacy, and life are frequently at odds with one another.

The state serves as the repository of all rights and decides whether to temporarily suspend Internet use when there is a threat to the lives of a sizable population or across a sizable geographic area, he said.

On the second day of the conference, Jain, an IPS officer from the 1980 batch, spoke on a panel titled “Criminal Use of ICT: Evolving a Framework for International Cooperation.”

Are Internet Shutdowns Following Law?

The number of mobile internet subscribers in India is the second-largest in the world. India also leads the world in the number of internet shutdowns, garnering the infamous moniker of “internet shutdown capital” of the world. The mobile internet was disconnected 127 times last year, but only 39 times so far this year.

In contrast, there were zero shutdowns in China and the US last year, two in Pakistan, two in Sudan, one in Iran, and two in Pakistan last year.

India accounted for 75% of the value lost from internet outages worldwide in 2020, costing an estimated $2.8 billion, according to a survey by the UK-based privacy and security research firm Top 10 VPN.

For instance, the new union territory experienced the nation’s longest internet outage following the abolition of Kashmir’s special status in August 2019, lasting 213 days. Even in early 2020, only 2G internet services were retained, and the prohibition on 4G speed internet persisted until February of this year. The internet was shut down 12 times in several areas during the demonstrations against the citizenship bill in December 2019.

India lacked a formal law authorizing internet shutdowns until 2017. District magistrates were given the authority to do so by Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

Under the Indian Telegraph Act of 1885, new regulations governing the ordering of internet shutdowns were enacted in 2017. The Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) laws stipulated that only the home secretary of the federal or state governments could now order the suspension of internet access. When “necessary” or “unavoidable,” during a “public emergency,” or in the “interest of public safety,” shutdowns may be mandated.

According to the written guidelines, the procedure is now both more challenging and transparent, both of which are positive developments.

On the ground, though, it’s different. Regulation non-compliance is all too frequent. District courts continue to use Section 144 to issue orders to shut down the internet.

Additionally, it appears from the updated Indian Telegraph Act regulations that to take down the internet must explicitly state their justifications.

Singh stated that any discussion on internet outages in India after January 2020 must start with the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Anuradha Bhasin case. The editor of Kashmir Times, Bhasin, filed a petition with the Supreme Court in 2019 alleging that media freedom had been restricted as a result of Jammu and Kashmir’s protracted suspension of mobile and internet service.

The freedom to access information is a fundamental right under Article 19(1)(a) of the constitution, and the freedom to engage in a trade, profession, or business over the Internet is also a fundamental right under Article 19(1)(g), according to Singh. These two points were explicitly acknowledged in the decision in Bhasin’s case.

Nevertheless, when issuing these orders, administrations just cite a protest. Singh cited Rajasthan’s internet ban, which was purportedly instituted to stop exam cheating. It demonstrates how fundamental rights are being ignored in favour of administrative convenience, he claimed.

Additionally, the majority of shutdown orders relate to mobile rather than broadband internet. Singh noted that as a result, those from lower-income groups are disproportionately affected by these closures.