Recent studies have pointed to a link between climate change and mosquitos, with the latter thriving under warmer temperatures.

Table of Contents

14 times more dengue cases than ‘96

Every inch of the country that is touched by a ray of sunlight is inhabited by mosquitos, and this is no poetic exaggeration. Ladakh, an area populated by rocky mountain passes that serve as walls against any threat, couldn’t keep dengue out with the recently-christened Union Territory registering its first two cases in 2022.

Thus the final victim is crossed out from dengue’s list, with the vector-borne disease present in every single state and Union Territory last year for the first time; a dramatic rise from 2001, when dengue cases were limited to only 8 states. 2024 is looking to continue down that road as cases skyrocketing throughout the country, with 31,464 cases recorded in July and counting.

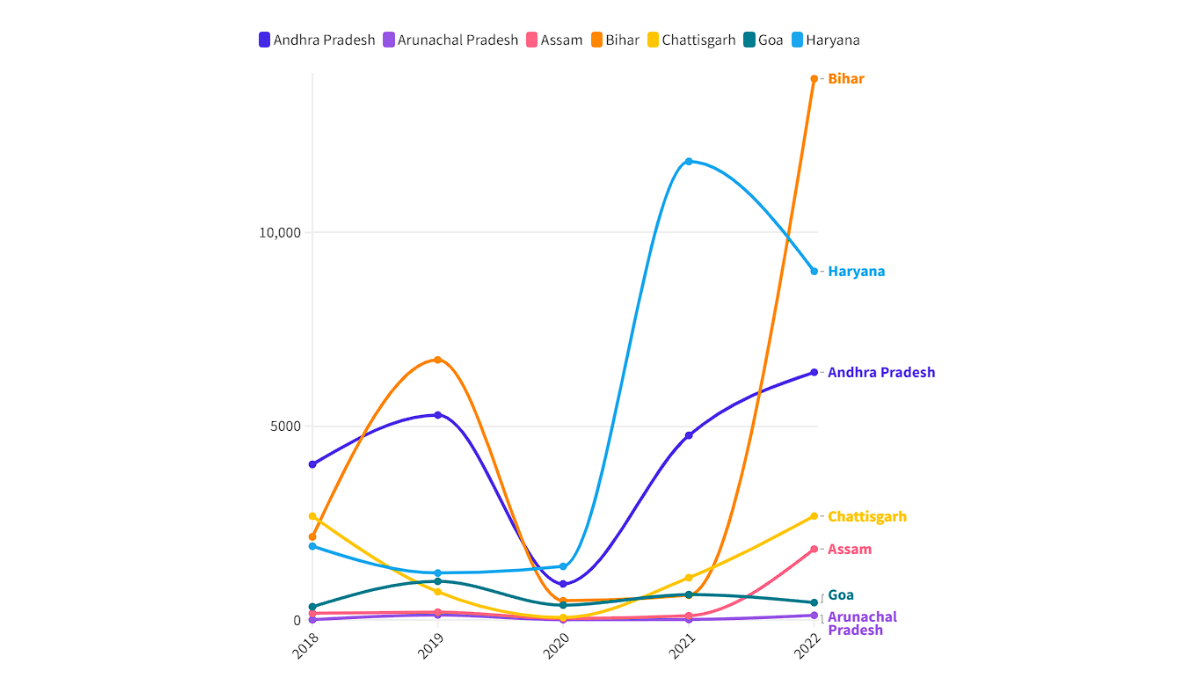

S P Singh Baghel, Minister of State of Health and Family Welfare, didn’t have the most encouraging words, stating that dengue cases have risen from 16,517 in 1996, to 2,33,251 in 2022; an uptick of 1312%.

Baghel attributed this alarming revelation to factors like a dearth in entomologists (those who study insects), frequent travel, not curbing the vector population sufficiently, along with insufficient cooperation from the public to prevent the spread of infection. However, his finger failed to point at one curious, yet impactful factor.

Climate change, according to Dr. Akshay Dhariwal, former director of the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), is indeed a factor behind the increased spread of dengue, among other vector-borne diseases. Evidently, the climate has a strong bond with the breeding and density of different arthropods (e.g. mosquitoes) who are generally the carriers of vector-borne diseases.

Other studies support Dr Dhariwal’s claims that the ever-worsening effects of climate change is helping mosquitoes spread dengue and other diseases in areas that were relatively untouched before. This is directly linked with deadly outbreaks seen in recent times, with infections of Zika virus, chikungunya, malaria and dengue causing global havoc. According to the World Mosquito Program, more than a million lives are claimed by such diseases, with over 700 million, or 1 in 10 people in the world, getting infected each year. These statistics are set to become worse if the planet continues to get warmer at its current rate.

Link between mosquitoes and climate change

Being hot-blooded creatures, we humans have been blessed with the ability to regulate our body temperatures to adapt to our surroundings. Mosquitoes, like other arthropods (a zoological term used for insects) are cold-blooded, and can’t survive in colder climates, thus left at the mercy of the weather.

Enter climate change, which has been driving global temperatures over the decades, and mosquito activity has mirrored that. Experts believe that global warming has expanded the geographical scope of where mosquitoes can multiply and thrive, which in turn, leads to more infections.

According to the Himachal Pradesh State Disaster Management Plan 2012, the hilly province was, just like Ladakh, was dengue-free until 2011, with cases now hovering around 4600 each year. This jump is in line with a rise of temperatures by 1.6 degree celcius in the northwest Himalayan area, as recorded by the 2012 report.

Gaurav Kumar and Shweta Pasi, from ICMR-National Institute of Malaria Research and authors of a study focusing on the rise of dengue in Himachal Pradesh, attributed that rise to many factors like urbanisation, globalisation, increased transport and insufficient preparation, but circled climate change as a major one.

According to a 2022 study from ICMR’s Ramesh C Dhiman and Syed Shah Areeb Hussain, climate change can allow mosquito species like the Yellow Fever and the Asian Tiger, to increase in population in areas of the Thar Desert and upper Himalayas.

Another implication of global warming is that higher temperatures have allowed mosquitoes to remain active for longer periods than seen before, which will lead to an increase in infections. Thus, India might witness a longer mosquito season in the coming years, according to experts.

However, global warming trends also provide a surprising silver lining. While they prefer warmer climates, too high of a temperature can cause a decrease in mosquito activity, and thus transmission of vector-borne diseases. For example, a 2019 study by Stanford Earth Matters magazine said that malaria spread is optimal around the 25 degree celsius mark, while the Zika virus spreads the most at 29 degree celsius. If temperatures exceed past those points, transmission becomes a struggle.

As a result, regions that are currently warm would see a decrease in vector-borne diseases as these regions become increasingly unfit for mosquitoes because of global warming. On the flip side, colder regions are at risk of witnessing more mosquito epidemics in the coming years as global warming pushes their climate into dangerous territory.

Higher temperatures, however, are not the only side-effects of climate change fuelling mosquito growth. Unusual patterns of rainfall, flooding, storms and the continuous rise of sea levels are some extreme events induced by climate change, and all of these work to leave stagnant pools of water for mosquitoes to thrive in. The very opposite situation also serves the same purpose, as droughts force people to scramble for water and store it in containers, which provides another avenue for mosquitoes to thrive and multiply.

Not just you, mosquitoes getting thirstier

Other than helping mosquitoes thrive and survive for longer, climate change also impacts how they reproduce. According to a 2009 study called ‘Local and Global Effects of Climate on Dengue Transmission in Puerto Rico’, warmer temperatures lead to mosquito eggs hatching faster, with the larvae growth also accelerated. Thus it takes less time for a mosquito to mature and go on the prowl, which is reflected in the increased rate of transmission of diseases.

In order to lay eggs, female mosquitoes nourish themselves by drawing proteins from our bloodstreams, called a “blood meal”. As a result of warmer temperatures, this blood meal is digested faster, making mosquitoes hungrier which in turn makes them bite more.