The widespread but ineffective insurrection against British rule in India between 1857 and 1859 is known as the Indian Mutiny, also known as the Sepoy Mutiny or the First War of Independence.

Indian soldiers (sepoys) working for the British East India Company started it at Meerut, and it later spread to Delhi, Agra, Kanpur, and Lucknow. It is frequently referred to as the First Independence War or other similar names in India.

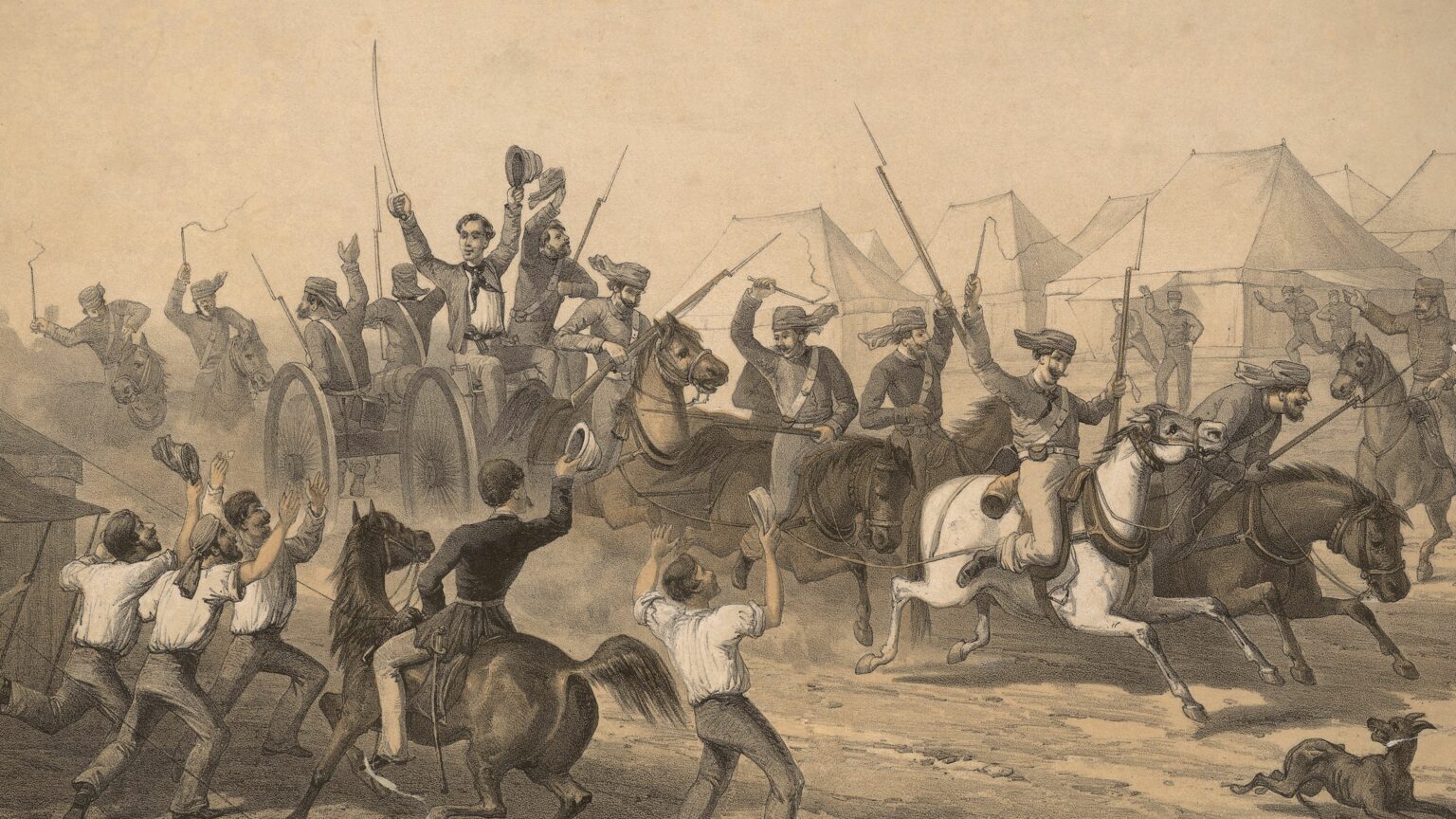

The Sepoy Munity

As a simple sepoy mutiny, about 1820 saw the introduction of British paramountcy or the idea that underestimating the underlying circumstances that led to the uprising might be likened to viewing it as Britain dominated Indian politics, economics, and culture.

The British increasingly adopted a range of strategies to seize control of the Hindu princely states that were affiliated with the British through what was known as subsidiary alliances. In every place, British bureaucrats were taking the place of the previous Indian aristocracy.

The theory of lapse, a classic British tactic, was originally applied by Lord Dalhousie in the late 1840s. It involves the British forbidding a Hindu ruler without a natural heir from adopting. A successor and annexing his territory upon the ruler’s demise or abdication. Those issues might

This was to be added to the mounting resentment of the Brahmans, many of whom had lost their incomes or prestigious positions.

The rate at which Hindu society was becoming more and more Westernized and being influenced by Western ideals was a considerable source of worry. The missionary questioned Hindus’ religious convictions. The philanthropic movement sparked broader political superstructure-level reforms.

While serving as governor-general of India (1848–56), Lord Dalhousie worked to emancipate women. He also introduced a measure to abolish all legal barriers to Hindu widows’ ability to remarry. Converts to Christianity were expected to split the family estate’s assets with their Hindu kin.

It was widely believed that the British wanted to undermine the caste hierarchy. The adoption of Western educational techniques posed a direct threat to both Hindu and Muslim orthodoxy. Because Indians were exclusively organized in the military, the revolt started in the Bengali army.

The release of the new Enfield rifle served as the justification for the uprising. The sepoys had to bite off the ends of lubricated cartridges to load them.

The sepoys had heard a rumor that the grease used to lubricate the cartridges was made of a combination of pig and cow tallow, making it offensive for both Muslims and Hindus to have oral contact with it. There is no concrete proof that any of the cartridges in question had either of these compounds on them.

However, the idea that the cartridges were poisoned added to the greater worry that the British were attempting to destroy traditional Indian society. In contrast, the British failed to pay adequate attention to the escalating Southeast Asian unrest.

Who is Mangal Pandey?

At the military camp in Barrackpore, a sepoy by the name of Mangal Pandey attacked British officers in late March 1857. Beginning in early April, the British detained him before putting him to death.

Later in April, Sepoy soldiers in Meerut rejected the Enfield cartridges; as a result, they were sentenced to lengthy prison terms, fettered, and imprisoned.

Their fellow soldiers were furious with this punishment, so they rose on May 10 and shot their British officers before marching to Delhi, where there were no European forces.

At that time, the neighborhood sepoy garrison joined the Meerut men, and by dusk, an unruly soldiery had ostensibly restored the ailing pensionary Mughal monarch Bahadur Shah II to power. The capture of Delhi served as a focal point and established a general course.

The whole revolt had a focus and a direction after Delhi was taken, and it then extended throughout northern India. None of the notable Indian princes joined the mutineers, except the Mughal rulers and their children, and Nana Sahib, the adoptive son of the overthrown Maratha Peshwa.

The British operations to put down the mutiny were divided into three parts, beginning with the mutineers’ seizure of Delhi. The summer saw desperate battles in Delhi, Kanpur, and Lucknow; the winter of 1857-58 saw operations around Lucknow directed by Sir Colin Campbell, and the early 1858 “mopping up” campaigns of Sir Hugh Rose. On July 8, 1859, peace was declared.

The ferocity that accompanied the mutiny was a bleak aspect of it. On rising, the mutineers frequently shot their British officers and were responsible for massacres in Delhi, Kanpur, and elsewhere.

The killing of women and children infuriated the British, but some British officers started taking harsh measures before they even realized such killings had occurred.

In the end, the repercussions far outweighed the original transgressions. In a frenzy of British vengeance, hundreds of sepoys were brutally killed or fired from cannons (though some British officers did protest the bloodshed).

The revolt immediately forced the Indian government to undergo a thorough clean-up. The British government disbanded the East India Company in favor of establishing direct sovereignty over India.

Although this had little immediate significance, it gave the government a more human touch and got rid of the dull commercialism that had persisted in the Court of Directors.

The mutiny-related financial problems prompted a modernization of the Indian administration’s economic position. Numerous changes were made to the Indian army as well.

The start of the Indian consultation policy was another important outcome of the revolt. In 1853, the Legislative Council was made up entirely of Europeans, and it acted haughtily as though it were

It was largely assumed that the situation had been exacerbated by a lack of connection with Indian opinion. As a result, an element nominated by Indians was included in the new council of 1861.

There were few disruptions to public works (roads, railways, telegraphs, and irrigation) and educational initiatives; in fact, some of these initiatives were sparked by the prospect of transporting troops in an emergency. But the callous social restrictions the British imposed on Hindu society ended abruptly.

The mutiny’s impact

The mutiny’s impact on the Indian people itself was the last factor. Traditional culture had voiced its opposition to the invading alien influences, but it had been unsuccessful. The princes and other natural leaders either stayed out of the rebellion or, for the most part, demonstrated they were

inept in part. From this point forward, there was a little more serious prospect of a return to the past or the exclusion of the West. A ” western” class system gradually took the place of India’s ancient social structure, giving rise to a strong middle class with a strengthened feeling of Indian nationalism.

Read More – Did you ever wonder why Britishers came to India?