On June 25, the World Health Organization declared that monkeypox is not a worldwide public health emergency.

The genetic material of the virus is now being examined by experts for hints as to how it has spread so rapidly.

As of June 24, at least 4,100 individuals in 46 nations have been infected with an illness resembling smallpox, which has since spread. In the United States, there have been at least 201 reports of this. According to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, those instances have been detected in 25 states and the District of Columbia.

Measures to halt the spread of the disease need “intense response efforts,” according to a statement from a WHO committee analysing the incident.

The declaration of a public health emergency may have made it simpler for persons who had been infected or exposed to the virus to get treatment and vaccinations. There are several treatments and vaccinations that may be used to prevent monkeypox, but they are only licensed for use against smallpox.

Although the monkeypox virus has just recently been identified, it is still a danger to human health. Since the discovery of the first human case of monkeypox in 1970, countries in central Africa where the disease is prevalent have seen intermittent outbreaks. Until 2017, there were few occurrences in western Africa. However, the majority of cases outside the continent were tied to travel and had a minimal impact on the rest of the world.

WHO director-general Tedros Ghebreyesus said in a statement announcing the decision: “Monkeypox has been spreading in various African nations for decades, and has been ignored in terms of study, attention, and financing.” For monkeypox and other neglected illnesses in low-income countries, this must change as the world is reminded once again that health is an interrelated concept.

Fewer than 10% of those who develop monkeypox die as a result of the disease. There has been at least one death as a result of the worldwide epidemic.

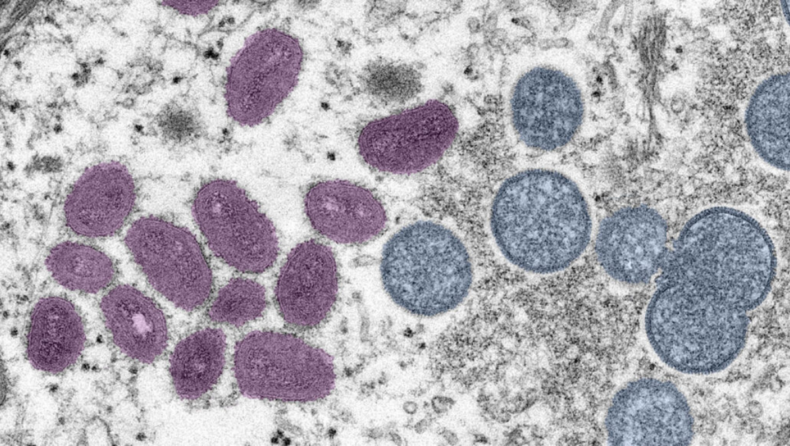

Scientists are scrambling to unravel the virus’ genetic code as the number of cases grows, hoping to discover if certain viral changes explain why the virus has spread so rapidly to new locations.

Deciphering the evolution

This suggests that the epidemic began in Nigeria, where the closest known related of the viral variants is located.

Since Nigeria’s monkeypox epidemic of 2017–2018, scientists have discovered more viral alterations than expected, which shows that the virus may have been circulating undetected among humans for some time. Many of these changes may be caused by a set of enzymes recognised for their virus-fighting activities in the body.

Genomic examination of monkeypox viruses linked to the worldwide epidemic from 15 victims across seven countries suggests that these viruses have on average 50 more genetic modifications than those circulating in 2018 and 2019. In other words, the virus has undergone six to twelve times as many changes as experts had predicted it would over that period. Poxviruses, such as the ones that cause smallpox and monkeypox, tend to evolve more slowly than other kinds of viruses.

Researchers believe that the modifications follow a pattern that is typical of an enzyme family called APOBEC3. Gs are changed to As and Cs to Ts in a precise manner by enzymes that use the letters G, C, A and T to symbolise the building blocks of DNA. This specific pattern was observed in the viral sequences, which suggests that the mutations are caused by APOBEC3s.

In a perfect world, a virus would be rendered inert and unable to infect any more cells since its DNA would have been completely replaced. APOBEC3 enzymes, on the other hand, may not be able to completely eradicate the virus. As long as the virus remains functioning, it may infect other cells and even spread to a new victim.

The genetic modifications observed in the monkeypox virus remain a significant issue, however, as to whether they are beneficial, detrimental, or do not influence all of the viruses.

Even though the enzymes are not directly responsible for the alterations in the monkeypox virus, scientists discovered that identical mutations continue to occur. As the virus spreads, APOBEC3s may continue to aid in viral evolution. Infectious pox lesions may be caused by a member of the enzyme family that is present in skin cells.

A variety of symptoms

There have been milder symptoms recorded in the current epidemic than in past outbreaks, which may have allowed the illness to spread before affected individuals even realised they had been sick.

At this point, it’s not obvious if the variances in symptoms are due to changes in the virus, according to Inger Damon, head of the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology.

Flu-like symptoms such as fever and tiredness are often seen in those who have been exposed to the virus within a week or two after infection. Approximately one to three days following the onset of these symptoms, an itchy, scaly rash with large pus-filled lesions appears, usually on the face and extremities, especially the hands. Symptoms of monkeypox are similar to those of smallpox, except the lymph nodes of monkeypox sufferers tend to swell.

Scattered or restricted to a single bodily place, “rather than diffuse and have not typically implicated the face,” Damon stated, “the lesions have been scattered, rather than diffuse and have not generally included [the palms of the hands or feet].” It’s possible to confuse the skin rash for a sexually transmitted illness like syphilis or herpes, according to the doctor.

The rashes haven’t spread to other places of the body in the majority of these situations. Symptoms such as fever have been “minimal and sometimes nonexistent before a rash occurs,” Damon added.

Close skin-to-skin contact or contact with infected towels, clothing, or bedding may spread monkeypox. Kissing or another close contact may also transmit it through saliva droplets. On June 23, U.S. Public Health Service captain Agam Rao told the CDC’s advisory committee on immunisation practices that the CDC is looking into whether the virus may be communicated by sperm or skin-to-skin contact during sex.

As Rao put it, “We have no reason to assume it is distributed any other way.”

There are more monkeypox instances among women in Nigeria than in the rest of the world, especially among males who have had sex with men. Monkeypox may infect anybody, but certain individuals are at more risk of developing a serious illness as a result, according to medical professionals. Immunocompromised individuals, youngsters, expectant women, and those with skin conditions such as eczema are among the most vulnerable.

A casual interaction with monkeypox in the United States poses a modest risk, according to Rao. However, based on the information she provided, instances of monkeypox have spread across the nation as well.

Monkeypox should be closely watched, is not a global emergency, says the WHO