Source: NASA

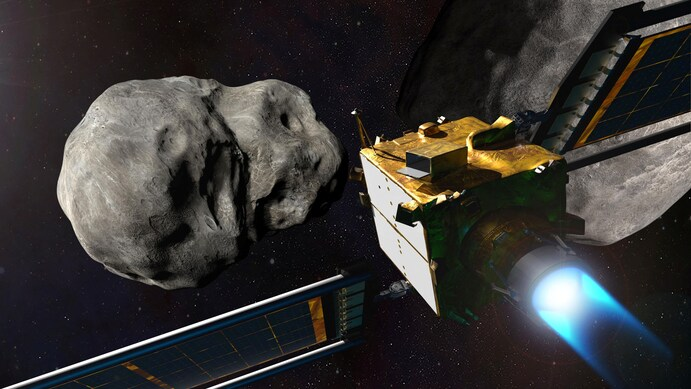

NASA on Monday slammed a small spacecraft into an asteroid, successfully hitting it at 14,000 miles per hour, to test whether such technology could be used to protect Earth from potentially catastrophic impacts.

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft’s violent demise exhilarated scientists and engineers at the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University in Laurel, Maryland, who were conducting missions under contract with NASA. pleased.

The asteroid, Dimorphos, is about the size of a stadium – or the Great Pyramid of Giza, as one scientist put it on Monday – and is currently about 7 million kilometres from Earth. It orbits a larger asteroid called Didymos. Does not pose a threat to our planet now or anytime in the near future.

It was just a test, NASA’s first demonstration of a potential planetary defence technique, called Kinetic Impactor. The idea is to create a hypothetical dangerous asteroid that only requires one hit to change its orbit. Launched last November from California, the spacecraft is small, about the size of a vending machine or golf cart.

Dimorphos is quite large – about 500 feet in diameter, though its exact shape and composition remained unknown until final approach. Scientists expected more debris from the asteroid upon impact, but no significant structural changes. It looks like a bug splashing on the windshield.

Nancy Chabot, a planetary scientist at the Applied Physics Laboratory, told reporters, “It’s not just bowling ball physics. The spacecraft will fail.

NASA plans to strike an asteroid now in case we really need to destroy one later.

But even small impacts on an asteroid’s motion can save the planet. An early collision with an asteroid, if done early enough – for example, 5 to 10 years before its expected encounter with Earth – could be enough to slow it down and cause it to crash. to slide.

There are thousands of potentially dangerous asteroids approaching or crossing Earth’s orbit around the sun. No one is currently known to have an orbit to strike the planet.

When engineers were designing an asteroid deflection mission, they came up with an ingenious idea that would dramatically reduce costs: hit a “moonlet” asteroid orbiting a larger asteroid .

Engineer Andrew Cheng told reporters that detecting the impact of a collision with an asteroid orbiting the sun would require two spacecraft, because such an asteroid travels at such an extreme speed. large and the impact of a small spacecraft will lead to the detection of the change. A second spacecraft should be present to observe the effect.

But one moonlet, like Dimorphos, orbits its larger twin moon at majestic speed. The impact of the collision will be easier to detect, both with telescopes on Earth and in space. No need for a second spaceship.

It will take at least a few days to know if the DART mission has been successful in slowing down the targeted asteroid and how well it has performed. Telescopes on Earth and in space observed the collision, as well as a small instrument called Cubesat, which was deployed 15 days before the collision. This is an unusual mission in that it does not involve a spacecraft attempting to survive a dangerous landing, said Robert Braun, head of space exploration at the Applied Physics Laboratory.

If all goes well, a NASA spacecraft will strike an asteroid on Monday.

“Here what we’re looking for is signal loss,” he told reporters before the collision. “What we encourage is the loss of spacecraft.”

By Monday afternoon, the Laurel engineers had submitted their final tweaks to the DART spacecraft, and from there it would make the final navigation adjustments automatically. The vehicle aimed directly at the larger, brighter asteroid, but was programmed to fire thrusters that would rotate it toward the smaller asteroid as it appeared.

Some odd scenarios cannot be ruled out as the asteroid’s shape will only be determined in the last hour before impact.In fact, 90 minutes prior to impact, only the larger asteroid—not Dimorphos—could be observed in the spacecraft’s live video feed.

“If we’re on the right track and it’s shaped like a donut, we’ll fly over it,” Braun said.

It was not until the last minutes of the DART’s journey that the spacecraft or its handlers returned to Earth to observe the Dimorphos. It was completely invisible until about an hour before impact. Even then, it was just a small, barely discernible speck next to its brighter twin.

There was fun in the Mission Operations Center as the asteroid appeared larger on the screen. Edward Reynolds, the project manager, started repeating the same phrase 50 minutes before impact: “It’s nominal, it’s nominal,” which is aerospace technical slang meaning “everything going on exactly as planned,” he claimed afterwards.

27 minutes before impact, engineer Elena Adams said, “We locked the Dimorphos.”

The onboard camera continuously clicks. That spot turns into a clear spherical rock with a rough surface covered with boulders, looking like something you would keep in the garage as a scrubbing tool. Engineers at the mission operations centre stood and celebrated the last few seconds because they were too thrilled to sit at their consoles. In the final image, the Dimorphos fills the frame completely. DART has reached an uptrend.

A blank screen then emerges. DART was a success, and it is no longer around.

“Impact confirmed on world’s first planetary defence test mission,” announced the NASA live stream.

On NASA’s wire, agency administrator Bill Nelson said the mission demonstrated technology “to save our planet.” Ralph Semmel, director of the Applied Physics Laboratory, said he felt an adrenaline rush when DART hit a live target: “Never have I been so excited to see a signal moving away.”

Click here to watch the video: