In the wake of a new outbreak of the Nipah virus in Kerala, experts have suggested that other states might not be detecting deaths and infections as much as Kerala.

Table of Contents

Kerala shuts shop, braces for 4th outbreak in 5 years

Two years from when it last rocked the nation, the Nipah virus has resurfaced in the Kozhikode district in Kerala, having already infected six people and claimed two lives since the early reports on August 30. Authorities have been hard at work to contain the deadly zoonotic (transmitting from animals to humans) virus, with 706 people having been tested as of 13th September, along with schools and offices being shut down indefinitely.

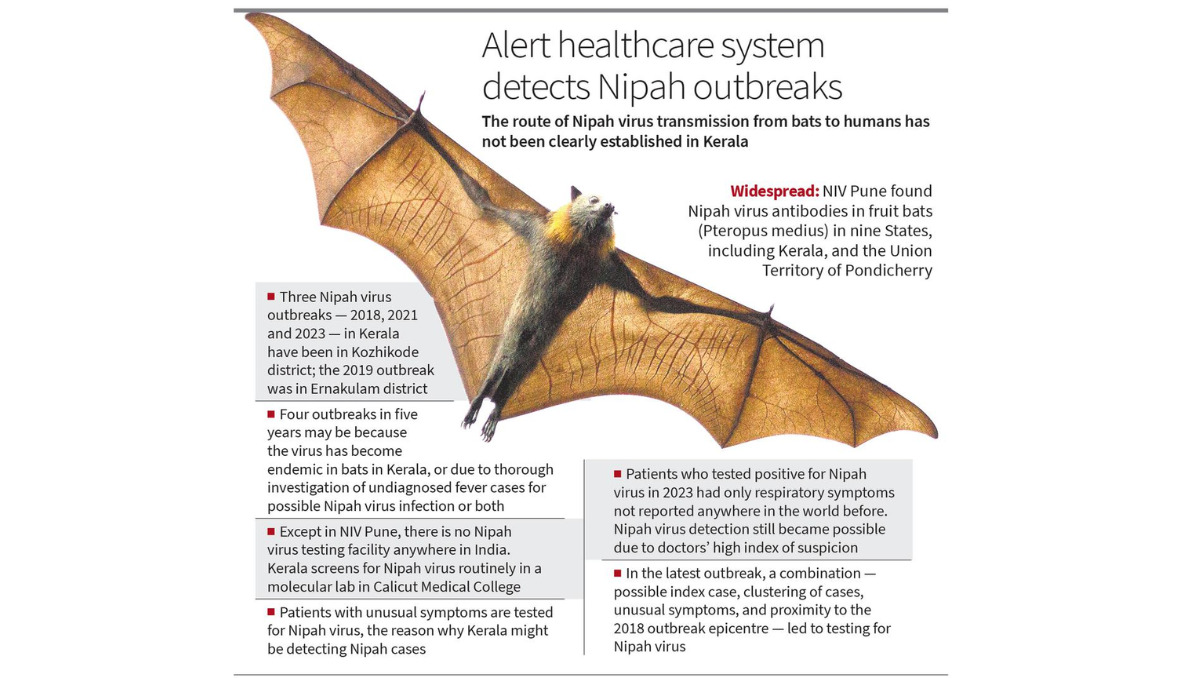

This has been the third outbreak in Kozhikode, and the fourth overall in India (2018, 2019, 2021, 2024), and according to Dr. A S Anoop Kumar, expert and Director, Critical Care at the Aster MIMS Hospital’s North Kerala Cluster, believed that the virus’ association with the state might be a result of other states failing to detect cases of their own, in an interview with the Indian Express.

From under their noses

In the first outbreak in 2018, it was determined that the source of the Nipah virus were fruit bats, as opposed to date palm sap, which were behind the outbreaks in Bangladesh, or pigs, which sparked infections in a Malaysian village called Nipah in 1999. An assumption could be made that bats carrying the specific strain of the virus are exclusive to Kerala, but Dr Anoop pointed to data that suggested that all Indian states, with the exception of some parts of Kashmir, house bats with Nipah virus antibodies.

Thus another reason could be that health workers in other states don’t possess a higher index of suspicion, which refers to identifying underlying issues on the basis of rudimentary observation. This, in turn, ensured that tests for the presence of Nipah Virus don’t occur, according to Dr Anoop, who asserted that healthcare workers in the state have been swift at taking precautions, collecting samples and flagging cases if even a small possibility of infection shows up. He added that there is no data which implied that fruit bats found in Kerala had a higher density of Nipah virus antibodies as compared to bats found in other regions.

The superiority of the Kerala healthcare system, deemed as such by NITI Aayog, might be contributing to higher cases in the state, along with higher literacy and awareness in the public. Literate people are more demanding of their doctors, which keeps healthcare workers on their toes when charting out a diagnosis, leading to more Nipah cases getting detected, Dr Anoop said.

West Bengal was another state which struggled with outbreaks in 2001 and 2007, but unlike Kerala, has been relatively quiet ever since. This, Dr Anoop said, could be down to the source of infection not being present in the area, thus protecting the people. Additionally, Dr Anoop claimed that cases in West Bengal were identified retrospectively, and screening tests happened only when the index of suspicion was high.

Newer symptoms found, possible Nipah virus mutation

Comparison between the current situation and what was witnessed in those panic-induced weeks 5 years ago also shone a light on the differing nature of symptoms. Since its discovery in 1998, Nipah virus cases all over the globe mostly caused encephalitis symptoms, which include brain inflammation, along with long-term neurological conditions such as seizure disorder and changes in personality. The same was seen in the 2018 outbreak in Kozhikode, according to Dr Anoop, where patients reported that they were feeling feverish and later developed neurological issues.

However this time, the majority of patients have been suffering with respiratory issues, with conditions escalating to severe pneumonia. The first person to be identified as positive for the Nipah virus was initially taken into care for a fever, which developed into severe pneumonia before leading to multi-organ failure and later death on August 30.

At the time of death, the case was officially deemed to be a matter of viral pneumonia and not Nipah virus, with the same happening when patient zero of the 2018 outbreak died. In the outbreaks of 2019 and 2021, only one case was identified as Nipah virus positive. Its possible that most of those who have caught Nipah virus might not be diagnosed as such, even if it results in death, Dr Anoop said.

The shift, according to him, can be attributed to the virus getting slightly mutated, with the National Institute of Virology in Pune testing whether the current strain of the virus is identical to the 2018 one.

Could urbanisation be a factor?

While institutions in India await for clearer data on Kerala’s vulnerability to Nipah virus, a Reuters investigation published in May blamed considerable deforestation and rapid urbanisation as the catalysts behind the outbreaks. According to experts, habitat loss has forced fruit bats to travel close to human settlements to forage for food, with contaminated fruit helping the virus spread to and through humans.