At the age of 90, Bao Tong has away. He was the highest-ranking Communist Party official to be detained in connection with the Tiananmen demonstrations that shook Beijing in 1989.

During pro-democracy demonstrations in the 1980s, he promoted political reform. However, the Communist Party ousted Bao and imprisoned him for seven years after putting an end to the campaign.

The announcement has received no response in his home country, where the internet is strictly blocked, even as Chinese activists from all around the world grieve his demise.

In the years that followed, any reference to the massacre, whose precise toll is still unclear, as well as the historic demonstrations at Tiananmen practically vanished from the public record.

Bao’s name is still unreachable on Weibo, China’s tightly controlled equivalent of Twitter. The message on the screen states that “applicable legislation and regulations” prevent their display.

Few young Chinese are familiar with Bao because of the Communist Party’s ruthless crackdown on any subject relating to the 1980s protests or any other type of dissent.

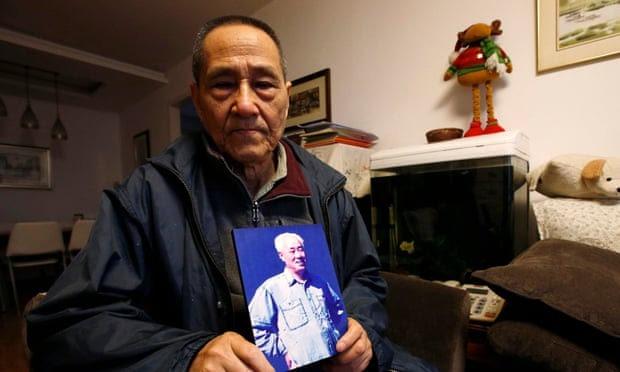

But after his son Bao Pu announced his passing on Wednesday, saying that his father had passed away peacefully that morning in Beijing, the place he had called home for decades, condolences flooded in from all over the world.

He was praised on Twitter by Wang Dan, a student leader from the Tiananmen uprisings, as a reformer and rebel who was essential to China’s opening up. He said that although while he was “against” the Chinese Communist Party, he still wanted to “show the highest respect” for former party members like Bao who battled for reform before departing.

Bao served as Zhao Ziyang’s top aide in the 1980s. Zhao Ziyang currently serves as Xi Jinping’s successor as general secretary of the Communist Party. Zhao had been a prominent member of the party wing that supported reform.

Bao, who was born in the eastern Chinese province of Zhejiang in 1932, entered the Communist Party in 1949, in the same year that it seized power on the Chinese mainland.

He worked his way up to become Zhao’s political secretary in the 1980s, then the general secretary. He worked as the party’s director of political reform and a member of the central committee.

Bao contributed to the creation of political and economic changes aimed at modernising the power structures that had remained essentially intact since Mao Zedong’s passing in 1976.

He was one of the designers of the model of group leadership that the party later adopted to prevent the concentration of power in the hands of one person.

But as the pro-democracy demonstrations swelled and spread throughout more of China in 1989, the hardliners in the party started to worry more about their future. Ultimately, the protests came to a terrible end as the reformists lost.

Days prior to the massacre on June 4, both Zhao and Bao’s careers abruptly came to an end. Both had expressed open sympathies with the protesters.

Zhao had already been demoted by that point and had lived the rest of his life under house arrest. 2005 saw his passing.

May 1989 saw the arrest of Bao, and 1992 saw his trial. He was charged with “revealing state secrets and counter-revolutionary propagandising,” which he vehemently disputed, and was pronounced guilty. He received a seven-year prison term in addition to being expelled out of the party.

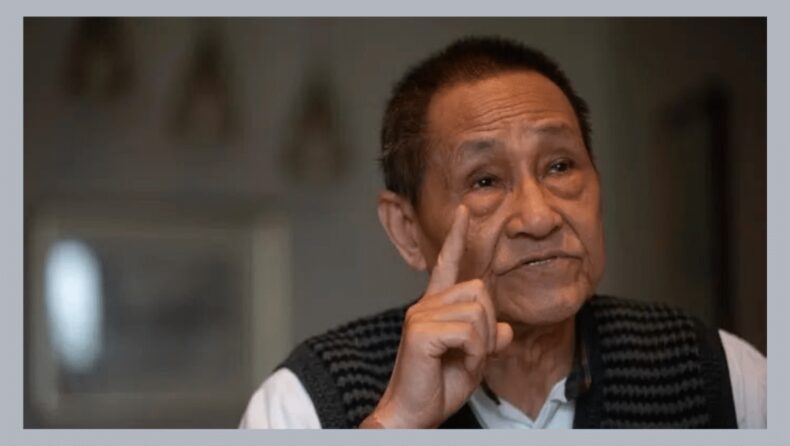

He continued to be closely monitored by the state even after his release. Nevertheless, throughout that time he rose to prominence as one of China’s most vocal dissidents and opponents of the party. He pushed for the Chinese government to recognise the protests and what transpired on “June 4,” the day of the massacre in Tiananmen Square.

He had been active on Twitter since 2012 and had frequently discussed Chinese politics there.

On the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen protests, Bao stated in an interview with BBC Chinese that he felt as though he had accomplished “nothing” in his life. He claimed that the future he had thought China would have and the political change he had campaigned for had never come to pass.

Jiang Zongcao, Bao’s wife, passed away in August of this year. She was 90 as well. Bao Pu and Bao Jian, the couple’s two children, were born.

Bao turned 90 a few days before he passed away. His son broadcast to the world what he believed to be his father’s final words: “It doesn’t matter whether I reach 90, what’s important is the future we all should fight for… we should do what we are supposed to do, then we’ll realise our value, the value of our life.”