In a recent research published in Nature, scientists have challenged the widely held belief of a distinct lineage that led to the complex origin of our species. For centuries, the study of human genome variation has hinted at the divergence of the human population emerging from a single ancestral community in Africa. The ‘out-of-Africa’ hypothesis consistently claims that early humans evolved about 150,000 years ago before moving to other parts of the world. However, it has been difficult to explain the emergence and dispersion of homo sapiens through the classical theory due to the scanty evidence of fossils and its uneven distribution across various geographical boundaries including, Ethiopia, South Africa, and Morocco.

A New Model for Human Evolution

The genomes of 290 living people were analysed by a global team of researchers from various institutions and were compared to existing fossil evidence to arrive at a new model for human evolution. According to the findings, numerous ancestral populations from all across Africa moved between different regions and interbred with one another for many years which contributed to the creation of Homo sapiens in a patchwork fashion. It also discovered that everyone alive now has ancestors in at least two different populations that lived in Africa approximately a million years ago.

An Altered Understanding of Ancestral Stems

Aaron Ragsdale, the study’s lead author, and a population geneticist, suggested that our species did not evolve from a single isolated location. The population structure of our ancestral groups was ‘weak’, which hints towards ongoing migration patterns that maintained genetic similarity across all the populations. Our origins lie in a deeply intertwined network of fragmented populations contributing to genetic intermixing, thereby validating the multiregional hypothesis.

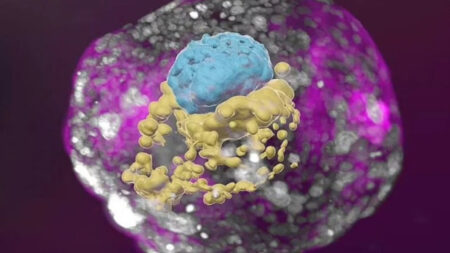

The study analysed the genes of different indigenous African populations and compared them to the genes of British individuals, including an ancient Neanderthal genome from Croatia. The researchers concluded that our ancestors lived in two different populations, which were categorised as Stem1 and Stem2. A tiny subset of Stem 1-derived humans split off to form the Neanderthals some 600,000 years ago. People continued to move between these stem populations and conceived children, leading to genetic intermixing and variation.

Major conclusions of the Study

According to the new model, the two populations may have united after evolving separately on opposite sides of the continent, eventually fragmenting into subpopulations. The scientists predicted that the variation in the stem populations accounts for 1- 4% of the genetic difference in modern human populations. As a result of living in an interconnected mesh of migrating populations, humans could preserve a higher proportion of genetic diversity, which may have helped them develop new adaptations or tolerate climatic changes.

People from Stem1 and Stem2 merged in southern Africa, creating a new lineage from which the Nama and other living humans descended. A distinct merger of the Stem1 and Stem2 groups happened somewhere else in Africa, creating a lineage that would eventually give rise to people who would live in West Africa, East Africa, and those who would spread outside of Africa.

The research concretised the belief that human evolution is a complex phenomenon with profound African roots that arose from multiple closely related populations. Due to the scarcity of fossil evidence, genome sequencing has become a revolutionary method for understanding the origin of the human species. Research models that rely on genetic data aid in constructing a link between the contemporary population and our ancestors.