One of the famous rivers through Karnataka is the Arkavati. Before finally draining into the Chikkarayappanahalli Lake close to Kanivenarayanapura, it rises in the Nandi Hills in the Chikkaballapura district and runs through Ramanagara and Kanakapura.

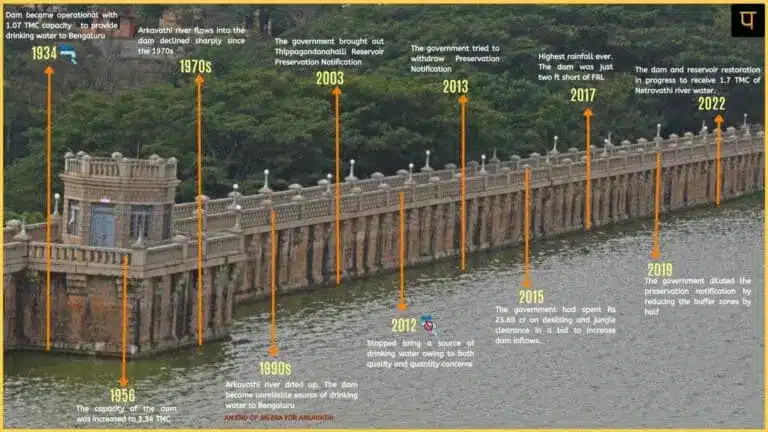

The 74-foot Thippagondanahalli reservoir is situated 35 kilometres from the city on Magadi Road. Since its opening in 1933, it has served as the city’s primary water supply source. It was constructed by Sir M. Visvesvaraya. Since 2012, the water in the reservoir has not been used for drinking. The 74-foot Thippagondanahalli reservoir is situated 35 kilometres from the city on Magadi Road. Since its opening in 1933, it has served as the city’s primary water supply source. It was constructed by Sir M. Visvesvaraya. Since 2012, the water in the reservoir has not been used for drinking.

Bangalore City places a lot of importance on The Arkavati. Two reservoirs—one at Hesaraghatta and the other at Tippagondanahalli—receive water from this river. The former was constructed in 1894, and the latter was put into use in 1933. In the Ramanagara district, a third dam called the Manchanabele dam is constructed.

The Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board uses the water from the first two reservoirs to supply 20% of the city’s water needs. This river provides the city with potable water in the amount of 135 million litres per day. The significant concern that requires attention is the recent decline in groundwater levels. An effective management strategy is needed to handle this. The key to determining the area where the best extraction and augmentation of current resources may be done is to highlight the groundwater potential zones. This work elaborates on the groundwater potential (GWP) mapping for the 866 km to Arkavathi sub-watershed, which includes Bangalore rural and Bangalore urban, two highly urbanised regions. A number of variables, including geomorphology, geology, soil, drainage density, lineament density, slope, land use, and rainfall variation, influenced the existence of groundwater as well as its origin and movement.

In many places, the river has dried up and turned seasonal. Many locals were shocked to see it in Torenagasandra in 2017 when it sprang to life following heavy rains because they had forgotten that the river had flowed through this region.

In the 1980s, the Arkavati’s water levels initially started to drop. Bengaluru’s growing development raised the need for firewood. The Forest Department responded by giving away free Eucalyptus saplings.

Many farmers turned their farmlands into Eucalyptus plantations because of the tree’s cheap labour requirements and a great return on investment. Eucalyptus is a water-intensive plant, and it eventually drained the groundwater supplies.

The economic backbone of Bengaluru is the River Cauvery. However, it was the Arkavathi before Cauvery. Arkavathi, which has been polluted and nearly dry for the past fifty years, is biologically dead. It serves as a tangible example of what lies ahead for Cauvery. Arkavathi, a victim of urban-industrial culture, only exists today as a dim echo of what once was a lovely river. A ghost river, that is.

This is the tale of how Bengaluru’s drinking water supply, the Thippagondanahalli Dam and Thippagondanahalli Reservoir (also known as Chamaraja Sagara), on the Arkavathi river, rose to prominence and, 80 years later, fell into disuse due to pollution and the lack of natural river flow.

This is also the tale of the Arkavathi River, which perished in the past century after existing for millennia.

Since Arkavathi’s passing, the Thippagondanahalli dam has stood as a symbol of the willful obliteration of the river that gave us our precious drinking water as well as the water needed for economic growth.

The situation on the Arkavathi River has not changed, but the Thippagondanahalli Dam has. It is being repaired to hold water from the perennial river Netravathi, which is located in the fragile western ghats 280 kilometres distant. In essence, the Arkavathi and Netravathi rivers were switched by the Thippagondanahalli dam.

Our knowledge of how our management of rivers has brought us dangerously near to running out of water depends on this thorough chronological narrative. It demonstrates how choices to over-exploit already-stressed rivers like the Cauvery arise.

The Arkavathi river is dying quietly and almost unnoticed, while a violent, bloody claim is being made for the water of the Cauvery river. This article serves as a constant reminder that there is obviously still much work to be done in order to maintain and conserve the rivers.