The law enforcers have neglected the moral enforcers that go against the constitutional boundaries to inflict their superiority. The rising graph of lynchings motivates the communities to inflict torture and deem it as justice.

What is lynching

lynching, a form of violence in which a mob executes a presumed offender, under the pretext of administering justice without trial, often after inflicting torture and corporal mutilation.

The term lynch law refers to a self-constituted court that imposes a sentence on a person without due process of law.

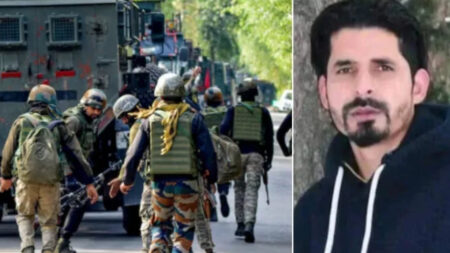

The victims of these lynchings were killed for ‘mere’ forwarded posts on social media. The messages circulated said that the people consumed beef, for anti-Hindutva sentiments, they ‘looked like a terrorist’ or alleged child-lifters.

Why lynching takes place

The reported killings proved that the mass sentiment and a high volume of fake messages could cost anyone their lives.

These lynchers come together based on an ideology, and they are systematically provoked to take actions that will send out a message.

These messages are primarily political and follow the agenda-setting theory to tell people that the ones who follow their ideology are right and those who don’t should fear them.

The victim’s background doesn’t matter in the case; the motive is to spread a message of fear throughout the community.

Records of the mob killings

Since 2012, India has witnessed 133 cases of mob lynching, according to a database of lynching incidents prepared by the data-journalism portal India Spend. Of the total 340 victims, 50 people lost their lives.

The data further revealed that 57 per cent of the victims were Muslims, and nine per cent were from the Dalit community. Yet, as per the home ministry, the National Crime Records Bureau does not record this data.

As a result of the lockdown, there was only one reported case in 2020. The National Crime Records Bureau does not record this data (NCRB).

Union minister of state for home affairs Hansraj Ahir told the Rajya Sabha (Upper House of Parliament) on 18 July, when asked whether the government “keeps record of incidents of lynching by mobs which are increasing across several parts of the country”.

The parliaments’ views on mob killings

In July 2018, the Supreme Court recommended that the parliament enact a special law to deal with cases of mob lynching.

The court passed a detailed judgment in Tehseen Poonawalla vs Union of India, issuing directions on the preventive, remedial and punitive measures to be adopted by the central and the state governments.

The judgment also recommended that the particular law by parliament should “create a separate offence for lynching” and impose “adequate punishment for the same.”

Yet, the home ministry has consistently stated in parliament that only state governments have jurisdiction over matters involving the police and public order—effectively washing its hands of the responsibility.

Its parliamentary responses indicate that the ministry has treated mob lynching as a state-level law-and-order concern and not a matter of “exigency” that threatens the country’s “secular ethos” and “pluralistic social fabric,” as observed by the Supreme Court.

Laws in the constitution

Lynching or mob killing, there are appeals made to put special legislation to deal with these crimes. The point missed is that such crimes are murders, and there are adequate laws under IPC and CrPC in place to deal with the murders.

“The legislators define mob lynching as an offence, and make a separate punishment for it. That should be then read with Section 302 of the IPC, because a murder is not justified, whether committed by an individual or a mob.

But the special act will expand the dimension of murder. Suppose a sentence of five years is legislated for being a part of the mob, and you will have life sentence for a murder charge.

What if a person is a part of a lynch mob, he or she cannot get away by saying, “I was only a spectator.” So, the trial will be held for being a part of a lynch mob and for murder or assault.

A silent spectator in a mob lynching case should also be treated as an accomplice to an offence of murder.” said Asad Hayat, a victim, Pehlu Khan’s lawyer.

There are different viewpoints to the introduction of special legislation. To stop the lynchings and mob killings, there must be humanity.

People come together to kill someone and not see it as a crime because of the deeply rooted hate against the communities and, to top it up: the blind faith and trust on social media.