By Harsha Josephine Antony | On Fri 9 Sept 2022 | 10.00 pm IST |

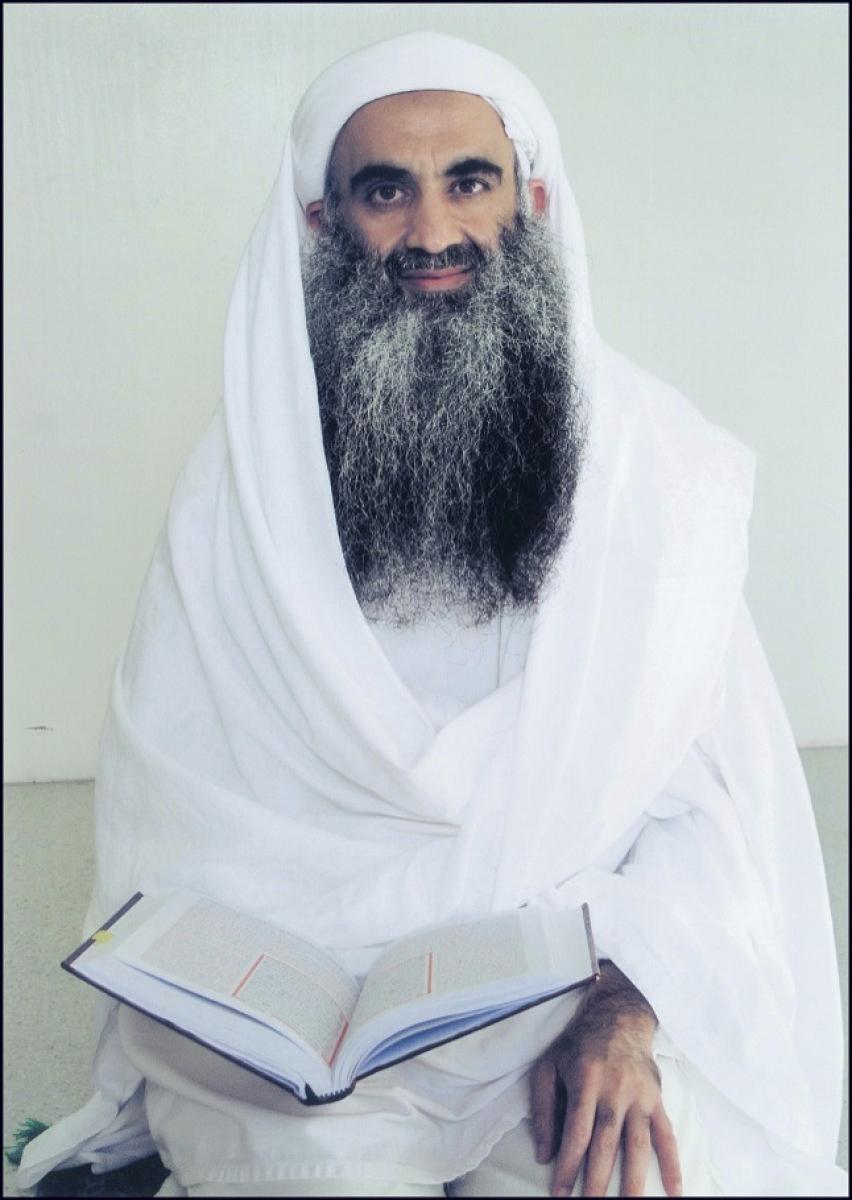

Photo credit: AP Photo

The U.S. achieved its most thrilling victory to date against the perpetrators of the Sept. 11 attacks with the capture of a dishevelled Khalid Shaikh Mohammed on March 1, 2003, after intelligence agents removed him from a bunker in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. The search for the third-ranking al-Qaeda figurehead took place over a period of 18 months.

The apprehension of a disheveled Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, taken away by intelligence officers from a bunker in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, on March 1, 2003, gave the U.S. its most exciting win yet against the perpetrators of the Sept. 11 attacks. It had taken 18 months for the world to search for the third-ranking al-Qaeda figurehead. However, America has taken a very long time to try and bring him to justice in a legal sense. It has been dubbed one of the critics’ worst failures in the war on terror. Mohammed and four other prisoners are still being held in a U.S. detention facility in Guantanamo Bay as the 21st anniversary of the terror attacks draw near. Their scheduled trials before a military tribunal have been continuously postponed.

The most recent setback occurred last month when pretrial hearings slated for early September were postponed. For the almost 3,000 attack victims’ families, the delay was just one more setback in a long line of disappointments. They’ve been hoping for a long time that a trial would provide answers and put an end to the speculation. Gordon Haberman, whose 25-year-old daughter Andrea died when a hijacked plane smashed into the World Trade Center, a floor above her office, said, “Now, I’m not sure what’s going to happen.” Andrea died after the hijacked airliner hit the World Trade Center. He made four trips from his home in West Bend, Wisconsin, to Guantanamo to observe the court procedures in person, but each time he returned disappointed. According to Haberman, “I think it’s crucial that America learns the truth about what happened and how it was done. Mohammed may be sentenced to death if he is found guilty at trial. “I personally want to see this go to trial.”

When questioned about the case, James Connell, a lawyer for one of Mohammed’s co-defendants who is accused of sending money to 9/11 attackers, confirmed reports that both sides are still “attempting to reach a pretrial agreement” that could still prevent a trial and result in shorter but still serious sentences. Former U.S. attorney for New York David Kelley, who served as co-chair of the Justice Department’s investigation into the assaults nationally, termed the delays and lack of prosecution “a horrific tragedy for the families of the victims.” He described it as “a huge failure” that was “as disrespectful to our Constitution as it is to our rule of law” to try Mohammed in a military court rather than a regular U.S. court system. He declared that it was “a terrible stain on the history of the nation.” Mohammed’s detention at Guantanamo in 2003 and the subsequent actions the US took with him after that are partially to blame for the difficulty in holding a trial for him and other detainees.

Mohammed and his other defendants were initially detained at undiscovered facilities abroad. Human rights organisations allege that CIA agents subjected them to enhanced interrogation procedures that were akin to torture in order to obtain information that would help in the arrest of other al-Qaida members. Mohammed was waterboarded 183 times, making him feel like he was drowning. A Senate investigation eventually found that no useful intelligence had been obtained as a result of the interrogations. However, it has resulted in never-ending pre-trial litigation over the question of whether FBI reports on their comments can be used against them; this process is not governed by the fast trial norms used in civil courts.

The possibility that the U.S. may have ruined its opportunity to try Mohammed in a civil court arose as a result of the claims of torture. But in 2009, President Barack Obama’s administration decided to give it a shot, declaring that Mohammed would be moved to New York City and put on trial at a federal court in Manhattan. Obama stated that “failing is not an option.” The transfer was never made, though, as New York City objected to the cost of protection. A military court would eventually try Mohammed, it was revealed. Following that, more than a dozen years went by. According to Kelley, many members of the legal profession who had been successfully pursuing terrorism cases in the decade before were astonished when talk of military courts first surfaced two decades ago. It “came out of the blue,” he claimed, for the idea of a tribunal. John Ashcroft, the attorney general at the time, claimed that nobody anticipated it because he opposed tribunals and had backed the federal terrorism investigations in Manhattan.

According to Kelley, it will become much more challenging to bring Mohammed to justice in a tribunal, let alone a trial, as time passes. The passage of time hasn’t softened the memories of the victims’ families or lessened their passion for witnessing justice. “Evidence becomes stale, witness memories deteriorate.” Lucy Fishman, the sister of Eddie Bracken, passed away at the trade centre. The New Yorker opposed Obama’s suggestion to move the trial to federal court because Mohammed is accused of “military conduct” and should be tried by the military. And even if he is a little annoyed by the delays, he comprehends them. “Everyone is staring at us and wondering, ‘What are they doing after all this time?'” He said, “But he is aware that the case “has to be done under a microscope” because it is something that the entire world is watching. “The wheels of justice turn. It’s up to the United States to perform its due diligence and ensure it’s done right.” They rotate slowly, yet nonetheless. And when the time comes, and everything is said and done, the world will be aware of what transpired.

Mohammed has been held at Guantanamo while Osama bin Laden, the head of al-Qaida, was murdered in a raid in 2011, and his deputy and successor, Ayman al-Zawahri, was recently killed in a drone strike. He spent three years plotting the 9/11 attacks, according to investigators with the military commission at Guantanamo Bay. They highlighted a computer hard drive taken when he was arrested, which they claimed contained images of the 19 hijackers, three letters from bin Laden, and details about several hijackers. Mohammed admitted in a written statement read aloud at his tribunal hearing that he had sworn allegiance to Osama bin Laden, that he had served on al-council, Qaida’s and that he had overseen the planning, organisation, execution, and follow-up of the September 11 plot “from A to Z” as bin Laden’s operations director.

In the statement, he also claimed responsibility for the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center, an attempt to shoot down American aircraft using bombs concealed in shoes, the bombing of a nightclub in Indonesia, and plans for the second wave of attacks following the attacks of 2001 that targeted iconic buildings like the Empire State Building in New York City and the Sears Tower in Chicago. According to the statement, he also claimed responsibility for additional planned attacks, including a conspiracy to kill Pope John Paul II around the same time as the murder attempts against then-President Bill Clinton in 1994 or 1995. Mohammed has spent nearly 20 years in legal limbo, unlike Ramzi Yousef, his nephew and the perpetrator of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing that claimed six lives, injured 1,000 others and left a crater in the parking garage below the twin towers. Ramzi Yousef was also imprisoned for a while, but Mohammed has not.

Yousef was found guilty in two separate civil courts and is serving a life sentence in jail. Although he was apprehended in Pakistan in 1995, he was transferred to the US for trial. Bracken visited Guantanamo in 2012 to observe one hearing for Mohammed and his co-defendants and would likely return if a trial occurred. At the time, Yousef said his right to kill people was comparable to the United States’ decision to drop a nuclear bomb during World War II. Mohammed has offered a similar justification, saying through an interpreter at a Guantanamo proceeding that killing people was the “language of any war.” “I’m not sure if I want to return there just to experience all the anguish and suffering again. But I suppose I would go if I were allowed to. Yeah. She’s that kind of a woman,” he said, “and my sister would do it for me. She was that kind of a woman; he later corrected himself.

Read More – Terrorist Threat In Bangladesh Is Real: US