Bladder cancer is a condition that affects a disproportionate number of men compared to women. While risk factors such as smoking have been identified, the reasons behind this gender disparity have remained unclear. Urologic oncologist Dan Theodorescu, renowned for his extensive research on bladder cancer spanning 25 years, has made groundbreaking discoveries regarding the association between the disease and damage to the Y chromosome. His latest study, published in the prestigious journal Nature on June 21, sheds light on this connection and its implications for understanding and treating bladder cancer.

Unveiling the Disproportionate Risk:

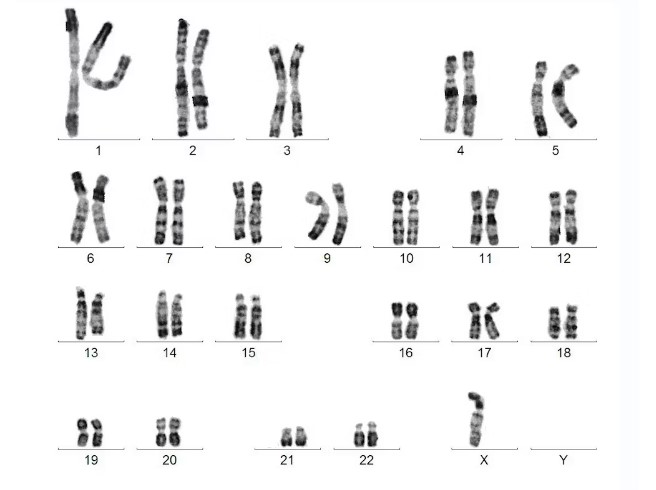

Men face a significantly higher risk of developing bladder cancer than women. Theodorescu’s research reveals that men have a 1 in 28 chance of developing the disease, while women have a 1 in 91 chance. Recognizing this stark disparity, Theodorescu embarked on a comprehensive investigation to unravel the underlying factors contributing to men’s heightened susceptibility to bladder cancer. While certain risk factors, such as smoking, had been previously identified, he directed his focus towards examining the role of hormones and chromosomes, specifically changes in the Y chromosome.

The Y Chromosome and Bladder Cancer:

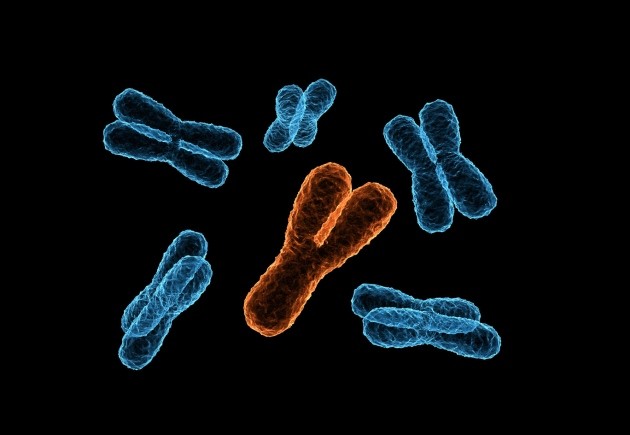

The Y chromosome, a genetic structure that differentiates males from females, undergoes natural degradation in some cells as men age. By the age of 70, approximately 40 percent of men experience partial loss of the Y chromosome. Previous studies have linked this loss to various health issues, including heart failure, Alzheimer’s disease, and premature death. Theodorescu’s study delves into the impact of Y chromosome loss on bladder cancer.

Experimental Approach:

The research team conducted experiments using bladder cancer cell lines derived from male mice. These cell lines were divided into two sets: one set of cells possessed an intact Y chromosome, while the other set had lost the Y chromosome. Notably, the tumor cells lacking a Y chromosome exhibited more aggressive growth compared to their Y chromosome-intact counterparts.

Further investigations involved combining 16 cancer cells with a normal Y chromosome and 16 cells lacking a Y chromosome. Surprisingly, both cell lines displayed a similar growth rate in vitro. However, when the same cell lines were transplanted into animals, the authors observed that tumor cells with a Y chromosome did not grow as robustly as those without a Y chromosome.

Understanding the Mechanism:

Although the cell models provided insights into the role of the sex chromosome in cancer development, they did not explain why bladder tumors lacking a Y chromosome exhibited accelerated growth. One plausible hypothesis suggests that tumor cells without a Y chromosome have an easier time evading the immune system, allowing them to grow faster. In order to explore this potential explanation, the scientists proceeded to introduce Y-positive and Y-negative cells into mice that had been specifically bred to lack an immune system. Surprisingly, both tumor cell types exhibited comparable growth rates in this immune-deficient environment. This finding strongly suggests that Y-negative cells somehow interfere with the immune system.

Implications for Bladder Cancer Treatment:

The study’s findings may have broader implications for understanding biological processes impacted by the disappearance of the Y chromosome. According to Chris Lau, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who conducts research on the human Y chromosome, this study could shed light on mechanisms contributing to other diseases where the immune system plays a role, such as those associated with mosaic loss of the Y chromosome.

Harnessing the Knowledge for Patient Benefit:

The ultimate question arising from this groundbreaking research is how it can be translated into tangible benefits for patients with bladder cancer. One potential avenue lies in the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors, a common form of immunotherapy. These inhibitors block the receptors that tumors utilize to send signals confusing T cells, while also educating T cells to recognize cancer cells.