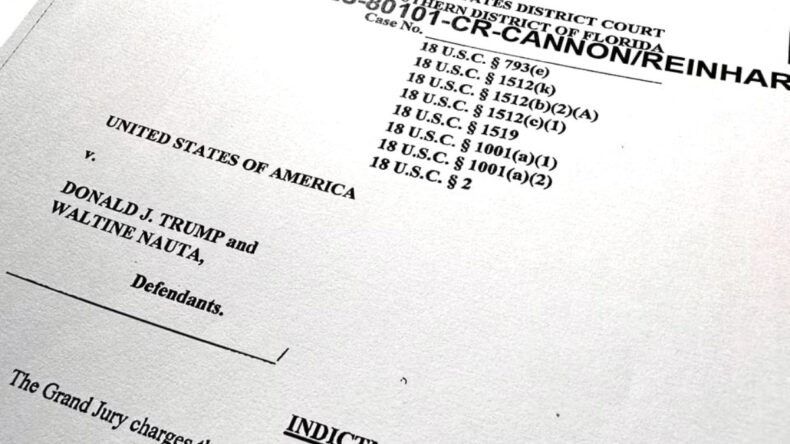

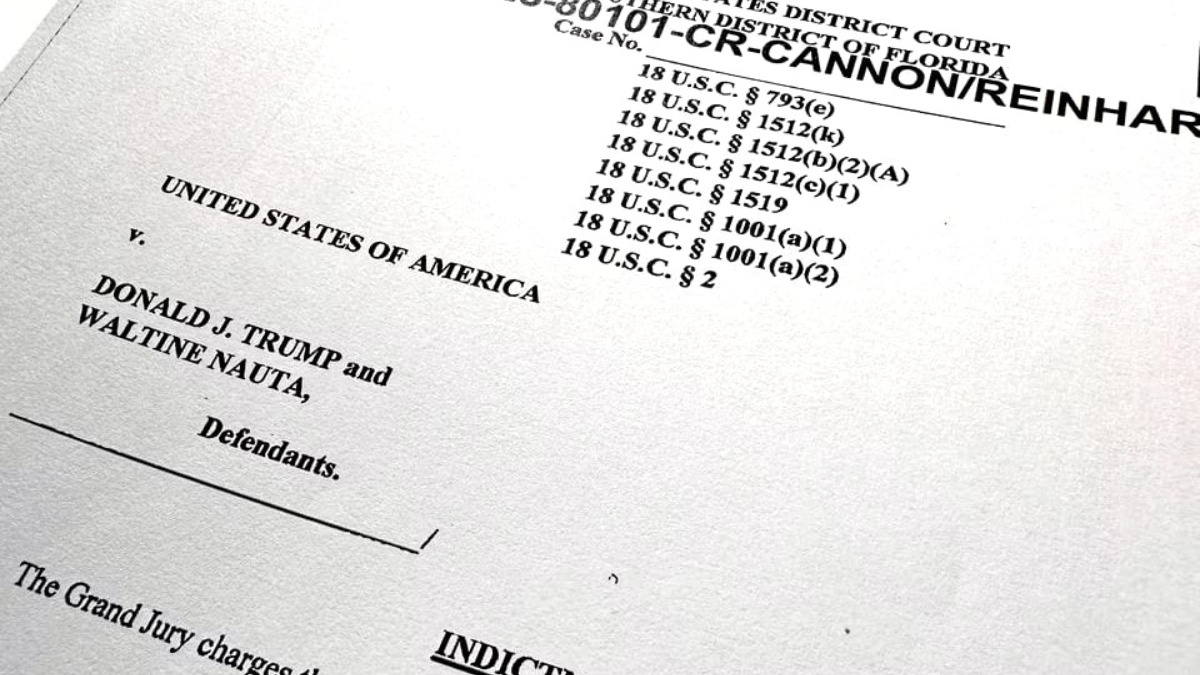

Security experts have stated that Donald Trump did not possess the legal power to declassify a document related to U.S. nuclear weapons, even during his presidency. This contradicts the claim made by the former president, who is now facing charges of illegally possessing the document.

According to the Atomic Energy Act, the secret document identified as No. 19 in the indictment against Trump for endangering national security can only be declassified through a specific process that requires the involvement of the Department of Energy and the Department of Defence.

For that reason, the experts said, the nuclear document is unique among the 31 in the indictment because the declassification of the others is governed by executive order.

Steven Aftergood, a government secrecy expert affiliated with the Federation of American Scientists, emphasized the irrelevance of the claim that Trump could have declassified the nuclear weapons information. According to Aftergood, the document was not classified through an executive order but rather by a legal framework, making Trump’s assertion regarding declassification legally inconsequential.

The unique nature of nuclear-related information undermines a defence strategy primarily focused on declassification, according to numerous legal experts. Trump’s assertion that he declassified the documents without presenting any evidence weakens his defence further, especially considering the specific rules governing the declassification of such sensitive materials. Additionally, the claim that declassification occurred prior to the documents’ removal from the White House lacks substantiation.

It is expected that prosecutors will assert the irrelevance of declassification in the case against Trump, as he faces charges under the Espionage Act. This Act, which predates classification procedures, criminalizes the unauthorized possession of “national defence information.” The term encompasses a broad range of secrets that could potentially aid the nation’s adversaries.

Document No. 19, identified as “FRD” or Formerly Restricted Data, bears the classification assigned to confidential information pertaining to the military application of nuclear weapons. The indictment characterizes the document as undated and specifically related to the nuclear weaponry of the United States.

RULES FOR NUCLEAR DATA

Despite pleading not guilty on Tuesday, Trump claimed that he had declassified over 100 secret documents while still in office, which he took to his residence at Mar-a-Lago in Florida. This assertion has been echoed by Republican lawmakers and other supporters. However, experts like Steven Aftergood have emphasized that the Atomic Energy Act (AEA) of 1954, which falls under the oversight of the Department of Energy for the U.S. nuclear arsenal, outlines a specific process for declassifying nuclear weapons data, which constitutes some of the government’s most tightly guarded secrets.

An anonymous former U.S. national security official familiar with the classification system affirmed that the statute is unambiguous and does not grant the president the authority to make declassification decisions. The most sensitive nuclear weapons information is classified as “RD” or Restricted Data, encompassing warhead designs, uranium and plutonium production, and more, according to the Department of Energy’s guide on classification.

While the Department of Energy may downgrade certain nuclear weapons data from RD to FRD (Formerly Restricted Data) for sharing with the Department of Defense, such materials remain classified. FRD materials include information on the size of the U.S. arsenal, storage and safety of warheads, their locations, and power. The declassification of FRD information is only possible through a process governed by the AEA, requiring the secretaries of energy and defense to determine the removal of the designation, as stated in a Justice Department FAQ sheet.

Divergent opinions exist regarding the president’s power to declassify nuclear data. David Jonas, who served as general counsel for the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration, argued that Trump possessed the constitutional authority to declassify all classified documents under the “unitary executive theory,” which asserts that Congress cannot limit the president’s control over the executive branch. However, Elizabeth Goitein, a national security law expert at the Brennan Center for Justice, maintained that Congress has the constitutional authority to restrict presidential power in most national security matters.

Although the president can request the declassification of FRD materials, the process involves the Department of Energy and the Department of Defense and can be lengthy, as pointed out by Thomas Blanton, director of the National Security Archive. According to Aftergood, FRD materials must be stored in a securely designated space, and the indictment’s allegation that Trump stored classified documents in a Mar-a-Lago bathroom would not meet the required standards.