A recent attack on a LGBTQ+ bar in Lebanon has led to activists question whether the hateful rhetoric serves as a distraction from the nation’s “real problems”.

Table of Contents

Lebanon not a LGBTQ+ safe haven anymore?

Compared to several Middle Eastern and northern African nations, Lebanon has been viewed relatively positively in terms of the safety provided to it’s queer citizens, with a landmark 2018 verdict ruling homosexuality as not an “unnatural offence”. While conservatism has been deeply embedded in Lebanon’s social fabric, bars, clubs, and civil society organisations have been tending to queer people in certain regions of the capital, Beirut.

However, queer activists from the country, along with several human rights groups have flagged an alarming uptick in the spread of anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment evident in the increasing assaults on safe spaces for the Lebanese queer population. The shift in intensity of the rhetoric and subsequent violence against queer people in Lebanon has been associated by many towards the general public being convinced by religious leaders and institutions that queer people are responsible for the nation’s recent hardships.

“It’s not us, it’s them”

Tarek Zeiden, the executive director of queer rights group Helem, derided politicians’ recent attacks on his community, instead pointing at economic policies to take the blame for causing “complete dissolution of the Lebanese family”, with financial hardships forcing many to look for better wages and livelihood abroad. In a Guardian article, Zeiden condemned the politicians over their “manufacturing of a moral panic” which allows them to mete out injustice without resistance and divert attention away from their unpopular policies.

Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of the Hezbollah movement, has been identified as a chief disseminator of anti-queer rhetoric, with recent speeches advocating for lethal violence against gay people “by all means necessary, without any limits”. He has accused NGOs and educational institutions of “spreading homosexuality to children”, castigating the community as a “real” and “imminent danger” in a televised speech on July 29th. A rise in online threats against queer people was observed by Human Rights Watch, with dating app Grindr having to step in to protect their queer users.

Mohammad Mortada, Lebanon’s acting culture minister, instead took aim at the blockbuster movie Barbie, calling for it’s ban on grounds of “promoting homosexuality and sexual transformation” along with offending “religious values and morality”.

On 23rd August, Christian extremists part of the ‘Soldiers of God’ group attacked a drag event happening at a Lebanon bar, with “at least two” attackers possessing guns, according to the performers. A video has surfaced on social media, where the assailants are shown pushing patrons around, accusing them of promoting “homosexuality in the land of God”, and warning them that “this is only the beginning.” According to those patrons, the authorities who arrived during the attack did nothing to intervene, but instead quizzed the bar owner and the attendees about the nature of the performance.

Co-founder of Helem and veteran activist Georges Azzi, forced to live in exile after facing harassment over his activism, saw Nasrallah’s comments as a strategy to manufacture an alleged attack on Lebanese society, one that can divert public attention away from the calamitous blast that rocked Beirut three years ago, killing more than 220 people, injuring thousands and causing great material and financial destruction. “Any subject that can distract people from this, they’ll take it,” he added.

Along with accusing gay people for “destruction of societies”, Nasrallah has also took aim at opponents of child marriage, claiming their activities are “unknowingly serving the devil”. Organisations and leaders belonging to different faiths have also echoed Nasrallah’s rhetoric, claiming to defend traditional family values.

The Maronite Christian patriarch recently organised a ministerial gathering, with caretaker prime minister Najib Mikati in attendance, concluding by claiming the queer community to be out of line with regards to religious and ethical principles, while laying down a warning against a “narrative cloaked in modernity, liberty and human rights rhetoric.”

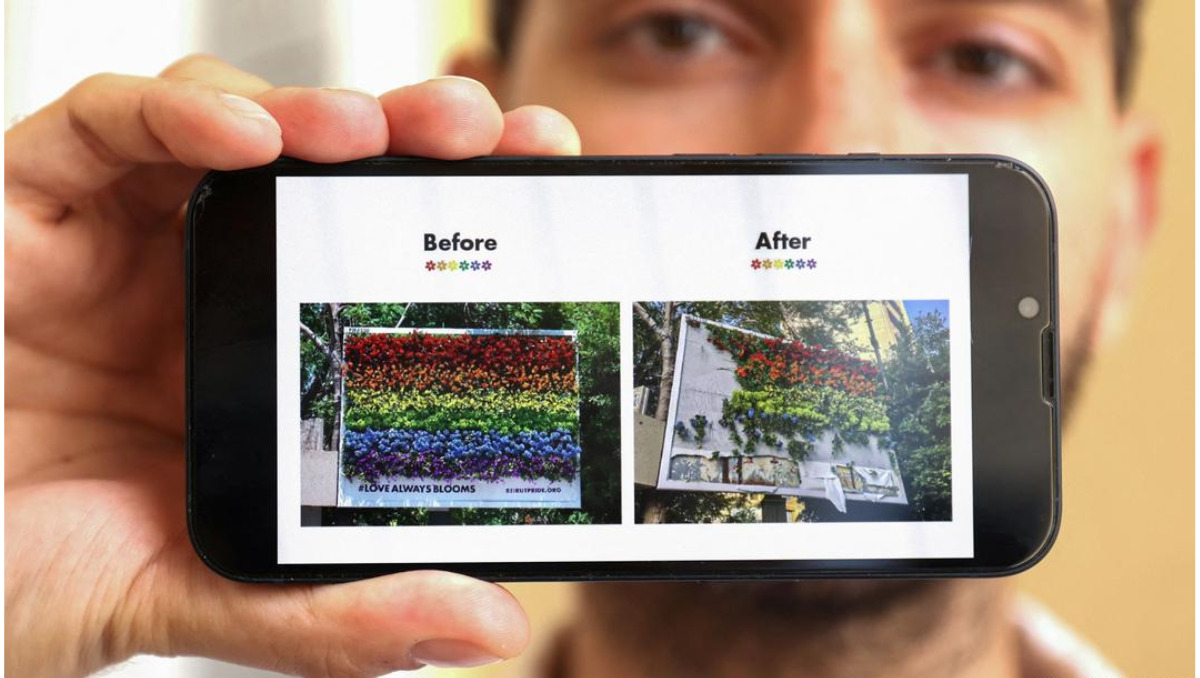

The burgeoning wave of anti-LGBTQ sentiment has been echoed in the legal sphere as well, with a directive issued in June last year by Interior Minister Bassam al-Mawlawi effectively prohibiting any pro-LGBT events. Despite a November ruling rendering that directive as unlawful and ordered it’s suspension, al-Mawlawi responded by issuing a second directive which banned any “conference, activity, or demonstration related to or addressing homosexuality.” Human Rights Watch has seen such steps as furthering the undermining of queer rights in Lebanon, with the community left powerless and defenceless against violence from fellow citizens and security forces, who have been accused of regularly interfering with human rights events since 2017.

The “real problems”

Advocates for queer rights in Lebanon have called for focus on, what they say, the real problems. Since 2019, a crippling banking and financial crisis has left citizens bereft of their savings. A complicated political situation and the absence of an actual president for over an year has fueled widespread animosity towards the government. Ramzi Keiss of HRW observed how the government has distracted the public from the urgent need for judiciary and economic reforms by using scapegoats. While refugees were the target during spring, now, he believed, the fingers have been pointed towards the LGBTQ+ community. “Lebanon is drowning”, he added.