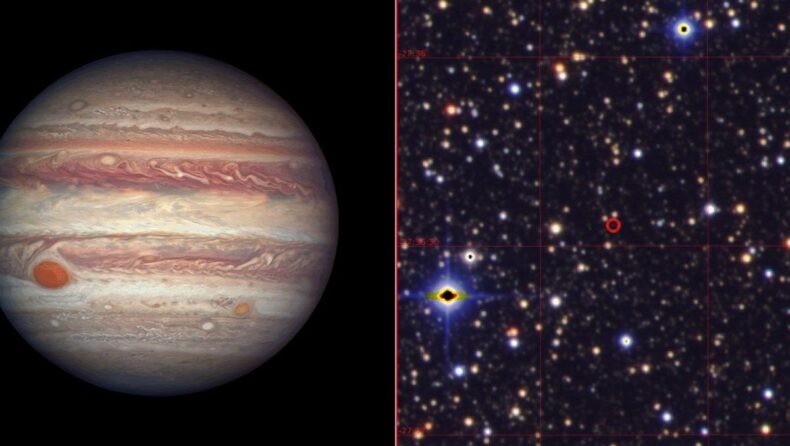

Jupiter is a distinctive planet in our Solar System, notable for its brilliant color schemes and overshadowed by a huge swirl of storms. Scientists have discovered that it is not unique and has a near-identical twin that is placed at a comparable orbit from its sun as Jupiter is from our Sun.

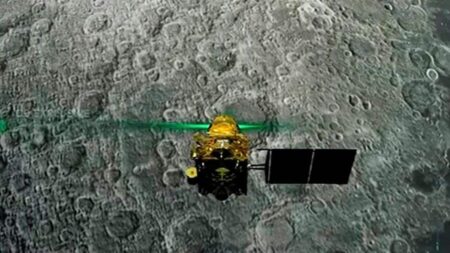

The exoplanet, known as K2-2016-BLG-0005Lb, was discovered by a multinational crew of cosmologists using data gathered by NASA’s Kepler satellite observatory in 2016. The telescope has discovered almost 2700 exoplanets in the Milky Way galaxy, but this Jupiter-like planet is twice as far as any previously discovered.

Lying 17,000 light-years from Earth, scientists utilized Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and a technique termed gravitational microlensing to detect this unusual world as it momentarily distorted and amplified light from a background star.

“To perceive the impact at all, the foreground planetary system and a background star must be almost perfectly aligned,” stated Dr. Eamonn Kerins, chief scientist with the Science and Technology Facilities Council.

“The odds of a planet affecting a background star in this way are tens to hundreds of millions to one.” However, hundreds of millions of stars may be found towards the center of our Galaxy. So, Kepler just stayed there for three months and observed them.”

Numerous teams had already scanned the same section of sky as Kepler. However, the space-based observatory was faster in detecting the anomaly due to its proximity to Earth, approximately 135 million kilometers.

The Kepler telescope, which operates regardless of weather or daylight, correctly estimates the mass of an exoplanet and its orbital distance from its home star.

It is essentially Jupiter’s identical twin in terms of mass and distance from its Sun, which is around 60% of the mass of our Sun, the scientists stated, adding that this was the first time a planet was detected using Einstein’s microlensing by the Kepler observatory.

This telescope was made to look at a part of the Milky Way galaxy. It was built to look for hundreds of Earth-sized and relatively smaller planets in or relatively close to the habitable zone, as well as to figure out how many of the hundreds of billions of stars in our galaxy could have these planets.

Before he retired, Kepler ended up spending nine years in interstellar space. Throughout that time, it found planets that are not in our planetary system. They could become habitable at some point in the future, but many of these planets are not yet ready.

Apart from the exhilaration of identifying an exoplanet with decommissioned equipment, the team’s discovery is notable since Kepler was not designed to detect exoplanets via this phenomenon. Keep in mind that the Kepler mission was extended in 2016, which is critical to keep in mind.

Kepler was initially planned to be utilized for the K2 “second light” mission but was abandoned following the failure of two reaction wheels. The mission would have involved the discovery of potentially habitable exoplanets by the spacecraft.

Since the mission’s certification in 2014, it has been extended significantly past the mission’s scheduled end date, until it ran out of fuel on October 30, 2018. In many ways, Kepler’s discovery of planets via microlensing is remarkable since the equipment was never meant to do so, Kerins said.

He continued by stating that future instruments, such as NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and the European Space Agency’s Euclid mission, may also be capable of exploiting microlensing to investigate exoplanets and therefore advance the field.

“On the other hand, these two characters were created particularly for this sort of work. As a consequence, they would be able to finish Kepler’s planet count “Kerins expressed her viewpoints. “In the following part, we’ll learn how common it is to design our solar system.

Additionally, the data will allow us to test our beliefs about how planets grow. This is an exciting new phase in our search for an alien civilization.”

As per the investigators, their discovery was detailed in a manuscript that was uploaded to ArXiv.org’s preprint site on March 31 and has been accepted for publication in the Royal Astronomical Society’s Monthly Notices.

Edited By : Khushi Thakur

Published By : Shubham Ghulaxe