Water is the one resource that all life on Earth requires, and the cycle of rain, rivers, and oceans is crucial to maintaining a stable and pleasant environment. Planets with water are always mentioned first when discussing where to look for indications of life throughout the galaxy.

Scientists are discovering evidence of an increasing number of planets in faraway solar systems as a result of improved telescope instruments. Similar to how examining a town’s population as a whole might show tendencies that are difficult to observe at an individual level, a bigger sample size aids scientists in identifying demographic patterns.

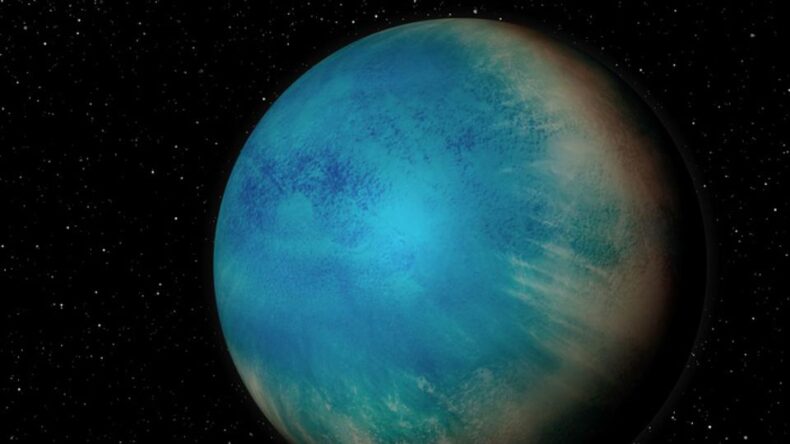

Rafael Luque, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago and the paper’s first author, stated that it was unexpected to find evidence for so many water worlds orbiting the most prevalent form of a star in the galaxy. It has significant ramifications for the search for terraforming planets.

Luque and co-author Enric Pallé of the University of La Laguna and the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands made the decision to examine a population-level look at a collection of planets that are detected orbiting an M-dwarf star. Numerous planets have been discovered so far around these stars, which are among the most frequent stars in our galaxy.

However, we are unable to see the planets themselves because stars are so much brighter than their planets. The shadow cast as a planet passes in front of its star or the slight tug on a star’s velocity as a planet orbits is the only faint effect that is observed by scientists. That means there are still a lot of unanswered concerns regarding the appearance of these planets.

According to Palle, “the two different methods of discovering planets each provide you different information.” Scientists can measure a planet’s diameter by observing the shadow that is cast as it passes in front of its star. Its mass can be determined by measuring the minuscule gravitational attraction that a planet has on a star.

In search of water worlds

It’s tempting to picture these planets as if they’re from Kevin Costner’s Waterworld: absolutely covered in deep waters. However, because these planets are so close to their suns, any water on their surfaces would be in a supercritical gaseous phase, causing their radius to expand. “However, we don’t see that in the samples,” Luque clarified. “This implies that the water is not in the form of a surface ocean.”

Water could instead be found mixed into the rock or in pockets beneath the surface. These conditions are similar to those found on Jupiter’s moon Europa, which is thought to have liquid water underground.

“I was shocked when I saw this analysis — I and a lot of people in the field assumed these were all dry, rocky planets,” said UChicago exoplanet scientist Jacob Bean, whose group Luque has joined to conduct additional research.

Despite the compelling evidence, Bean and the other scientists would like to see “smoking gun proof” that either of these planets is a water world. That is what scientists hope to accomplish with JWST, NASA’s recently launched Hubble successor space telescope.

Read More: Expedition of ISRO’s SSLV until now