Displaced citizens and activists have questioned whether demolition of Delhi slums in recent months was a part of “beautification” in the run-up to the G20 summit.

Table of Contents

Removing poverty, or the poor?

India has claimed the presidency for the G20 summit this year, taking place on the 9th and 10th of September in the capital city of Delhi. Widespread preparations have been taking place in full swing as Public Works Department (PWD) workers attempt to give Delhi a makeover in time, from installation of lamp posts, fountains, statues and CCTVs, to maintenance of pumps across the city to prevent waterlogging.

However, another prominent component of the municipal government’s activities have been mass demolition drives over slum areas in various parts of the capital since the opening months of this year, with hundreds of thousands left displaced and without a roof over their heads.

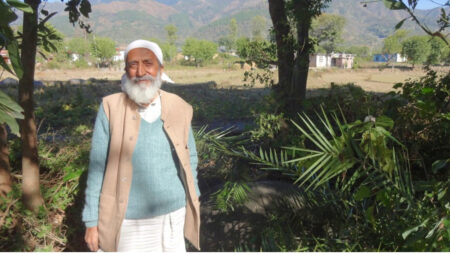

Jayanti Devi, 56, expressed her fright when the bulldozers and officials arrived to raze the shanties near Pragati Maidan, the summit’s main venue, before she hurried to collect whatever was left of her belongings in the rubble, what was once her home for nearly 30 years. “They destroyed everything. We have nothing left”, said Devi while talking to CNN.

Citing the “illegal” nature of such dwellings as a justification, the government deemed such the removal of such structures as “a continuous activity”. But residents of now-demolished slum localities, along with activists have suggested that the drives were instead a part of the “beautification” work for the summit in an attempt to impress foreign officials. The government has since denied such allegations with a written response to the parliament in July.

Feeble roofs above majority of heads in Delhi

Amongst the 16 million people that reside in Delhi (according to the Census of 2011), only 23.7% live in housing that can be deemed as “planned” or “approved”, with the rest having no choice but to turn towards slums and shanties as an alternative, says a report from Delhi-based think tank Centre for Policy Research.

Most houses in slum areas take shape in a patchwork like manner from years of cumulative efforts. Majority of residents find their livelihoods not far from their localities, which they have been calling home for decades.

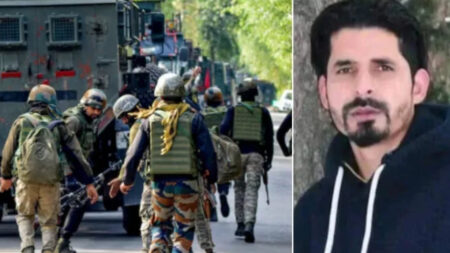

Hardeep Singh Puri, the minister for housing and urban affairs, stated that “unauthorised colonies” house some 13.5 million Delhiites in a parliament session in 2021. This year in July, the junior minister of the same ministry, Kaushal Kishore, claimed that at least 49 demolition drives have taken place in the capital within the timeframe of April 1 and July 27, resulting in reclamation of around 230 acres of government land. Additionally, he also denied that demolition of such “illegal” dwellings was in any way done to “beautify the city for the G20 summit”.

Sunil Kumar Aledia, executive director and founder of Centre for Holistic Development, doubted Kishore’s statements, accusing the government of showing neglect towards the vulnerable classes. He added that residents should’ve received a warning prior to the demolitions so they can look to options elsewhere, if removal was necessary. This fell in line with a Supreme Court ruling made last month, which stated that squatters are not entitled to occupy public land, and can only request for more time to vacate their “illegal” dwellings and apply for rehabilitation at best.

Residents of the Janta Camp shanties adjacent to an open drain near Pragati Maidan, however, were shocked when bulldozers arrived four months ago, with footage showing residents in an unconsolable state as they haplessly watched their houses made of tin sheets get torn apart and levelled into the ground. Mohammed Shameem, a resident, was hopeful that the upcoming G20 summit would bring about hope, as the “big people” attending the summit could provide “something to the poor”. Disillusioned, he remarked that the opposite is happening, with “big people” sitting on their graves and eating.

Harsh Mander, a social activist whose work centres around homeless families and street children, commented how the Indian State feels shameful of “ostensible poverty”, seeking to cloud it from the people who come to visit the country.

Dharmender Kumar, a resident at Janta Camp and a clerk working at an office in Pragati Maidan, was distressed over the larger ramifications of his house getting razed, which included a negative impact on his children’s education who attend a government school nearby. His family, including wife Khushboo Devi and her father, were asked to leave their dwellings on the pretext that “the area had to be cleaned”. Talking to Reuters, Devi was disapproving of the government’s actions, instead suggesting that if the poor looked so bad, they could shroud them behind a curtain or a sheet.

A history of destruction on the path to G20

Before the May demolitions was the April demolition drive conducted around the Tughlaqabad Fort area, carried out by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), who justified their actions by accusing residents of encroaching illegally on the land and creating settlements. Savita, a resident, was distraught when the bulldozers came, depicting scenes of people crying, screaming and begging the officials to stop. “People have been living here for over 40 years. Why didn’t authorities demolish these homes earlier? Why now?”, she added.

Even before those demolitions, were the efforts undertaken as a part of the preparations for the 2010 Commonwealth Games, taking place in Delhi. The Indian National Congress, the then-ruling party, employed similar measures, wherein beggars were taken away from the streets while slums were, again, destroyed, leading to major disruptions in lives of thousands of marginalized people.

Muffling the voiceless?

In the buildup to the much-anticipated summit on the 9th and 10th, PM Modi has been observed to create an image of India as the leader of the global south and emerging economies. Modi, in several speeches, depicted India as a modern superpower, a voice to the poor, while expressing the intent to touch upon and shine a light on the global south’s major concerns. Activists however, have looked to emphasise on the irony of the situation. “People are dying on the streets in the cold winter and we are demolishing homes”, said Mander.