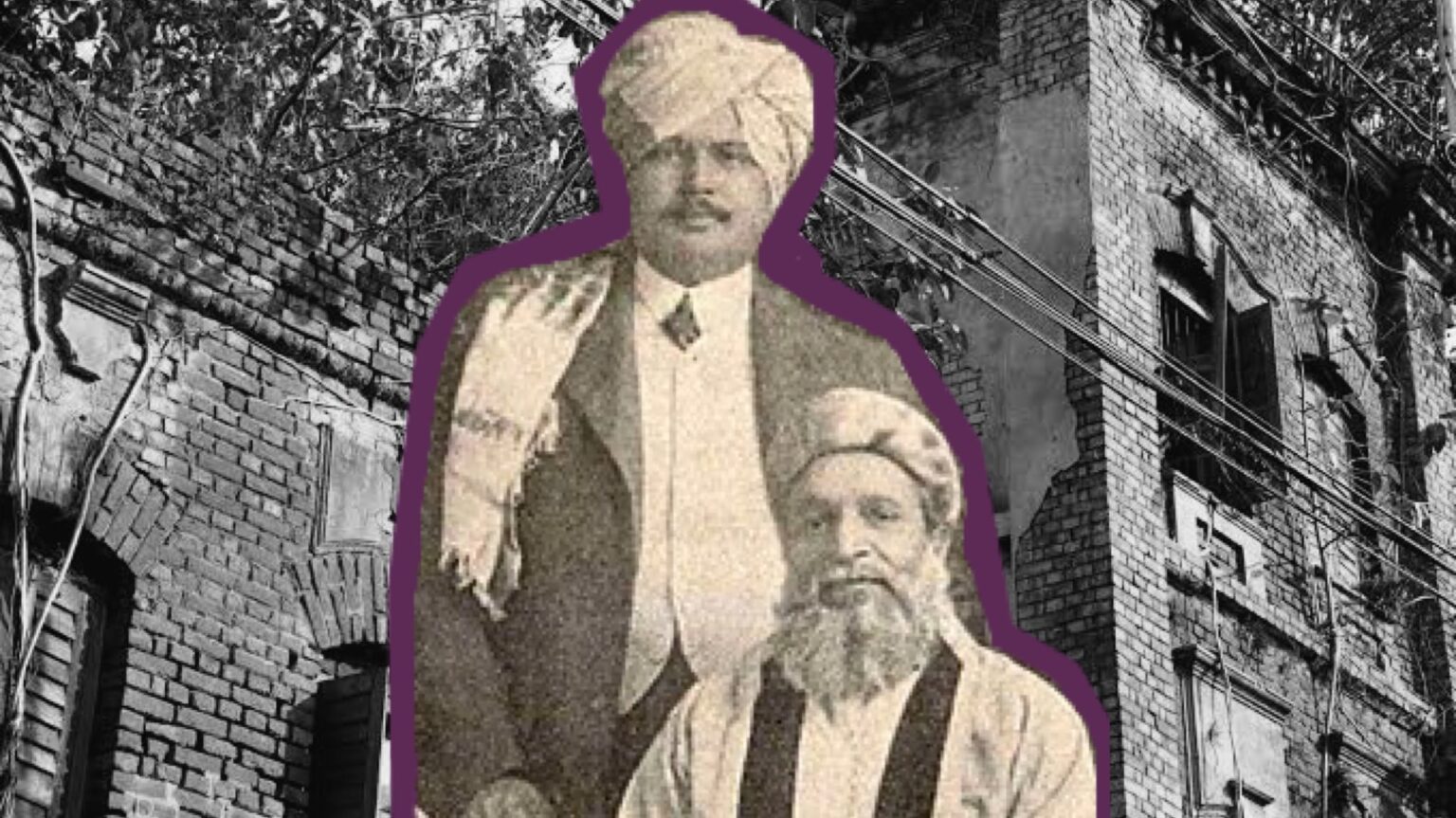

At 12 Wellington Square stands the relics of a palatial residence of one of Calcutta’s ( Kolkata’s)most influential historical figures.

It was the epicenter of the most prominent intellectual and political movements the city ever saw.

Bipin Chandra Pal, CR Das, Ganesh Sakharam Deuskar, and Bal Gangadhar Tilak were frequent visitors to this house.

Sri Aurobindo stayed at the house during his time in Kolkata in 1906.

The National Council of Education was set up on its grounds and Rabindranath Tagore would meet with Sri Aurobindo here to discuss policy and philosophy.

Raja Subhodh Mullick’s late 1800s mansion today is just a hollow ghost of what it once was – an empty shell, its grandeur is gone and its glory diminished practically to nothingness.

The house was declared a heritage building in 1998 and is now owned by the University of Calcutta. According to reports, a long-dragging court case has prevented its maintenance for several decades.

Such has been the fate of many of Kolkata’s grand ancestral homes. The city’s unique architecture used to be an artistic marvel.

As these mansions decay due to neglect and ill-treatment and new buildings crop up in their place as homeowners sell to contractors out of desperation and lack of government aid, a precious cultural treasure is lost.

Utilitarian architecture is taking over, but at what cost?

Changes in a city’s dominant architectural style reflect the historical and cultural transformations its people undergo.

It reflects the shifting values of the city residents and the emergence of new needs that need to be accommodated.

City architecture evolves over time and is a natural process. Yet, for Kolkata, formerly Calcutta, the change is not entirely positive.

The dilapidation of the city’s architectural wealth has been accompanied by the rise of utilitarian architecture – buildings several stories high, designed merely to accommodate its growing population.

Read Also: AIIMS RUNNING ON MANUAL MODE FOR 5 DAYS NOW

The lack of effective urban planning on the government’s part lets developers and contractors have a lot of liberty.

The new properties are developed to serve only the utilitarian function to accommodate and cheap and unimaginative design is, therefore, the most profitable.

Calcutta used to boast ancestral homes, each unique in their design with their red oxide floors, ornate Venetian glass windows, corinthian pillars, and intricate relief sculptures adorned with familial motifs.

The disappearance of these buildings is a horrifying testament to Calcutta’s cultural decadence and stagnation and its fall as the intellectual and artistic capital of India.

The silence is deafening while the shouts are drowned

What is perhaps the most astounding is the absolute inaction on part of the authorities and the government.

There is hardly any aid provided to preserve privately owned heritage buildings.

Furthermore, government-owned buildings only see slow and minor repairs between the gap of years when they need urgent restoration.

Dalhousie Square, named after British Governor-General Lord Dalhousie is the site of several prominent heritage buildings including the Grand Post Office, Stephen House, the Currency Building, St. Andrew’s Kirk, and the Writers’ Building designed as the offices of the junior clerks or “writers” of the East India Company.

The Writers’ Building was the administrative office of The Government of West Bengal until a renovation project was announced in 2013.

The Public Works Department has progressed at a snail’s pace as the chaotic expansion of Kolkata Metro threatens the other buildings around Dalhousie and other parts of central Kolkata, like Bowbazar.

Residents of the city have raised alarm but it seems their concerns are falling on deaf ears. Restoration projects, backed by individual citizens and private institutions have been protecting some of the heritage buildings but without large-scale intervention from those in power, the future is bleak.