Dopamine levels alter primarily in reaction to inputs from the outside world, according to conventional scientific understanding. Pavlov was famous for training his dogs to salivate when they heard a bell rather than seeing food.

Scientists now believe that the ringing of the bell generated a release of dopamine to signal the impending reward.

Researchers questioned if mice might control their spontaneous dopamine impulses if Pavlov’s dogs could control their cue-based dopamine responses with a little training.

To test this, the researchers devised an experiment in which mice were rewarded for increasing the strength of their spontaneous dopamine impulses.

They formulated an analysis in which mice were compensated for expanding the strength of their unconstrained dopamine motivations.

The Experiment

A group of scientists recently discovered that they could train mice to voluntarily increase the amount and frequency of seemingly random dopamine impulses in their brains, casting doubt on reward theories in learning.

They could, essentially, train mice to improve the sum and recurrence of apparently arbitrary dopamine driving forces in their cerebrums, giving occasion to feel qualms about remuneration hypotheses in learning.

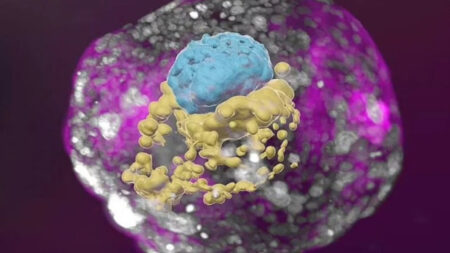

The researchers fostered another strategy for estimating dopamine in the brain of mice, in 2014. Conrad Foo found that neurons in mice’s brains discharge tremendous eruptions of dopamine, known as driving forces, for reasons unknown.

This happens at random intervals, but around once a minute on average. The research team devised an experiment in which mice were rewarded for increasing the strength of their spontaneous dopamine impulses.

The mice were able to increase not only the strength of these dopamine releases, but also the frequency with which they happened. The dopamine motivations re-established to their past levels when the capability of a prize was taken out.

The New Age Alternative to Pavolov’s Dog?

Wolfram Schultz, a neuroscientist, found during the 1990s that the brain of an animal discharges dopamine when it anticipates an award, not just when it gets one.

This showed that the neurotransmitter can be made in response to the expectation of a prize as opposed to the genuine award — what could be compared to Pavlov’s dog. Nonetheless, dopamine is made in the two conditions because of some type of outside boost.

While there is always a tiny amount of random background dopamine “noise” in the brain, most neuroscience studies have not examined the idea of large-scale random dopamine impulses that could affect brain function and memory.

These findings cast doubt on the concept that dopamine signals are deterministic – that they are created exclusively in response to a cue – and, in fact, cast doubt on several basic learning theories that currently exclude huge, random dopamine impulses.

Dopamine has long been assumed to allow animals to determine which stimuli will lead them to a reward.

A progression of prompts is habitually utilized – for instance, a creature might be attracted to the sound of surging water, which is trailed by the prize of drinking.

This observation of dopamine bursts that occur spontaneously rather than in response to a signal do not fit easily into this framework.

Huge neurotransmitter unconstrained floods could interfere with these chains of occasions, impeding a creature’s ability to associate roundabout prompts to rewards, as per recent discoveries.

The capacity to actively manipulate dopamine bursts could be a strategy for mice to mitigate this theorised learning difficulty, but further research is needed.

The Unexplored

The need to interface the current discoveries to dopamine-flagging spaces of the cerebrum is yet to be found.

The effect of spontaneous impulses on the ability to learn in terms of behaviour, for instance, navigating or forging through a laboratory maze, still remains unknown.

It’s enticing to hypothesize that unconstrained motivations could be deciphered as a deceptive expectation of remuneration. It’s possible that animals’ spontaneous impulses give them hope that a reward is “out there.”

The ideal point is to see in case there’s a connection between dopamine’s unconstrained desires and mice branching out to explore their current circumstance. At long last, regardless of whether the driving forces help or weaken mental capacity is obscure.

It is a wonder in case there is a connection between unconstrained motivations and psychological well-being on the grounds that the neurotransmitter receptors in the cortex are the very receptors that are overexpressed in schizophrenia.