Syrian Prisoners have come forward to share their experience of ‘Salt Rooms’, operational during the period of President Bashar al-dictatorship. The rooms were built as a substitute for refrigerators to store dead bodies. Bodies were kept in the rooms until they were filled for a truck load. The great irony here is the ultimate desire of salt in common lives and the overarching use for purposes of storing bodies.

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a monitoring organisation based in Britain, up to 100,000 people have perished in Syrian regime jails since 2011, constituting a fifth of all combat fatalities.

The Story of Amin

The prisoner Amin (changed name)was startled to find himself standing ankle-deep in what seemed to be salt when a Syrian guard threw him into a poorly lighted chamber. The terrified young man had spent the previous two years incarcerated in Sednaya, Syria’s largest and most infamous jail,currently it was the winter of 2017.

After spending all that time largely devoid of salt in his meagre prison diet, he eagerly brought a handful of the coarse, white crystals to his tongue The second, more gruesome surprise arrived shortly after that: as barefooted Amin cautiously made his way across the chamber, he stumbled upon an emaciated corpse that was partially buried in the salt.

Amin quickly discovered two more remains that had been partially dried off by the mineral. He had been placed in what Syrian prisoners refer to as “salt rooms,” which are crude morgues built to preserve corpses in the lack of refrigerators.

Salt Rooms

To keep up with the widespread prison massacres carried out by President Bashar al-dictatorship, Assad’s these corpses were being handled in a manner already known to the embalmers of ancient Egypt.

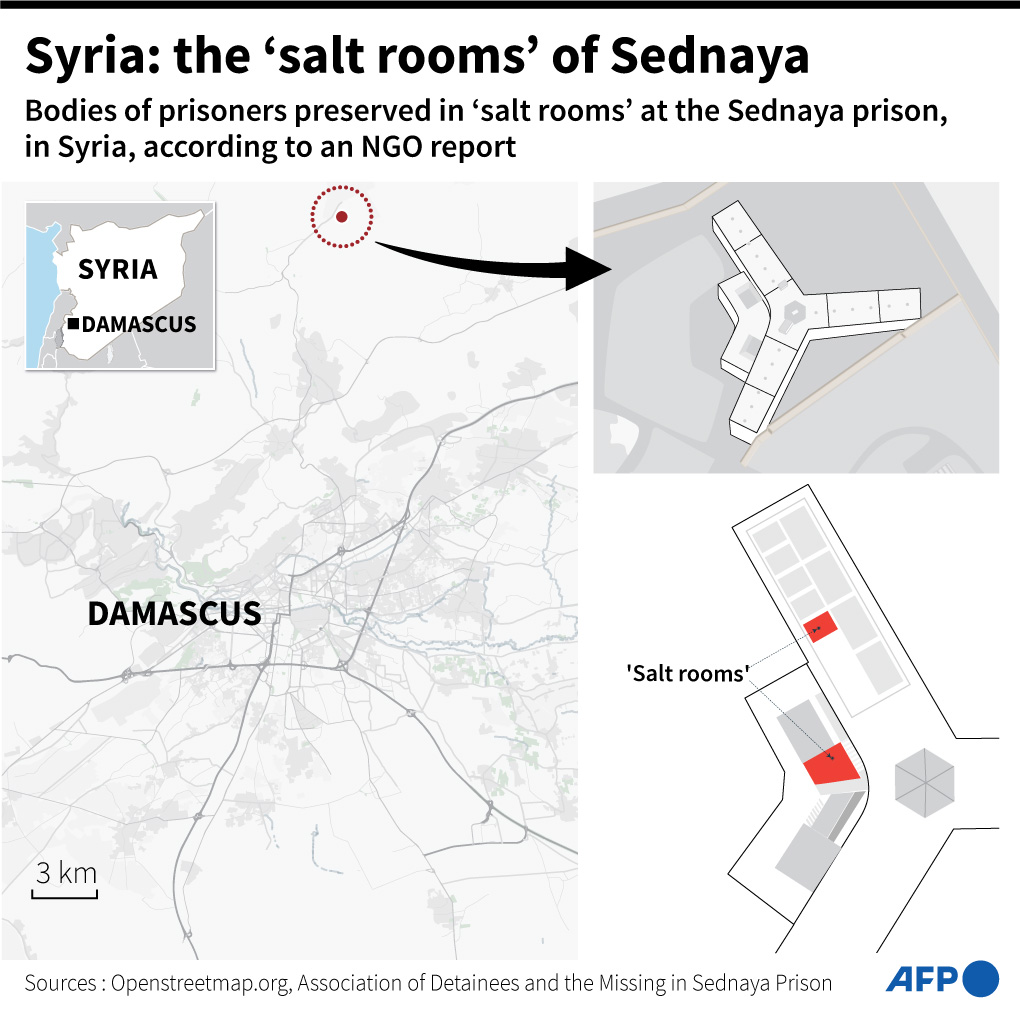

In a forthcoming report by the Association of Detainees and the Missing in Sednaya Prison, or ADMSP, the salt rooms are described in full for the first time. AFP discovered that at least two such salt chambers were constructed inside Sednaya through further investigation and interviews with former prisoners.

Abdo, a 30-year-old resident of eastern Lebanon who is originally from Homs, requested that his true name not be used because he fears retaliation against him and his family. He recalled the day he was tossed into the salt room, which acted as his holding cell before a military court trial, while living in his little rented apartment in an incomplete building.

He remarked, “At first, I pleaded that God would not have mercy on them. “They have so much salt, yet they never use any of it on our food!

“I stepped on something cold after that. It was someone’s”

His heart stopped.

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a monitoring organisation based in Britain, up to 100,000 people have perished in Syrian regime jails since 2011, constituting a fifth of all combat fatalities.

The salt room on the first floor of the red building was described by Amin, who was fortunate to have survived, as a rectangle around six by eight metres (20 by 26 feet) in size with a crude toilet in a corner.

He recalled how he cried and recited verses from the Koran while curled up in a corner and believed that his fate would be death and execution. Amin survived to tell the tale, and the guard ultimately came back to lead him to the court.

He had observed a group of body bags close to the door as he was leaving the room.

Based on blanket terrorism allegations, he had been imprisoned alongside tens of thousands of others. He was released in 2020, but he claims the ordeal left him permanently traumatised.

He declared, “This was the hardest thing I’ve ever gone through.”He remarked that in Sednaya, his heart stopped. He wouldn’t feel anything if my brother’s passing were revealed right now.

Since the start of the crisis, Sednaya alone is said to have housed almost 30,000 individuals. Only 6,000 had the fortune to leave that hell.

In what has grown into a significant racket, death certificates rarely reach the families unless they make a hefty bribe. As a result, the majority of the others are officially listed as missing.

Moatassem Abdel Sater, another former prisoner who was questioned by AFP, described a similar incident that occurred in 2014 in a different first-floor cell measuring roughly four by five metres and lacking a toilet.

The 42-year-old recalled finding himself standing on a thick layer of the type of salt used to de-ice roads in the winter while speaking at his new home in the Turkish town of Reyhanli.

“To my right, there were four or five dead,” he remarked.

Moatassem remarked that their skeleton limbs and scabies-covered skin resembled his own malnourished frame, saying, “They looked a bit like me.” They appeared to have been mummified.

On the day of his release, May 27, 2014, he was led to the makeshift morgue. He stated he still has no idea why, but speculated that “it might have been just to intimidate us.”

The Dark World of Salt

Image Source- Al Jazeera

The ADMSP dates the first salt room’s establishment to 2013, one of the war’s worst years, after conducting thorough research on the infamous prison.

Diab Serriya, a co-founder of the organization, stated in an interview in the Turkish city of Gaziantep, “We learned that there were at least two salt rooms used for the bodies of individuals who died under torture, through sickness, or from hunger.”

The existence of both rooms at the same time and if they are still in use now were also unknown.

According to Serriya, when a prisoner passed away, his body was normally kept in the cell with the other prisoners for two to five days before being moved to a salt room.The bodies stayed there until a truckload’s worth could be hauled away.

The next destination was a military hospital, where death certificates were prepared before mass burials, frequently listing “heart attack” as the cause of death. According to Serriya, the purpose of the salt chambers was to “preserve the remains, control the stink, and protect the guards and prison staff from diseases and viruses.”

Joy Balta, an anatomy professor located in the US who has published widely on methods for preserving human bodies, described how salt could be used as a quick and inexpensive substitute for cold rooms. He told AFP that because salt can dehydrate any living tissue, it can be utilised to dramatically slow down the process of disintegration.

According to Balta, who developed the Anatomy Learning Institute at Point Loma Nazarene University in San Diego, a person can be preserved in salt for longer than it can be kept in a specially constructed refrigeration chamber without disintegrating, “but it will affect the superficial anatomy.”

It is known that the ancient Egyptians practised mummification, which involves submerging the body in a salt solution called natron.

The greatest salt flats in Syria, Sabkhat al-Jabul, are located in the Aleppo area and are supposed to have provided the tonnes of rock salt used in Sednaya.

The ADMSP research is the most in-depth analysis to date of Sednaya’s organisational structure, which has produced horrific amounts of mortality for years. It offers thorough schematics of the and of the division of responsibilities between various army units and wardens. No one is permitted to know anything about Sednaya, the dictatorship wants it to be a “black hole,” Serriya stated. “Our report disputes that for them.”

Salt, a Treasure

Over the past three years, the combat in Syria’s deadly civil war has subsided, but Assad and the prison that has become a memorial to his bloody rule are still in place.

As overseas survivors continue to share their memories and investigations into regime crimes by international courts fuel a push for accountability, more facets of the horror of the conflict continue to be revealed.

Serriya stated, “If there is ever a political transition in Syria, we want Sednaya to be made into a museum, like Auschwitz.”

In addition to suffering from disease and abuse, prisoners recall that hunger was their greatest hardship.

The fact that the salt they so desperately desired was a component of the horrifying death machine that was destroying them also strikes the ex-inmates as a horrible irony. They occasionally consumed wheat, rice, and potatoes, all of which were prepared without salt or sodium chloride, a mineral that is essential for human health.

Low blood sodium levels can result in nausea, lightheadedness, and cramping as well as, if left untreated, coma and death.

Detainees once added salt to their water by soaking olive pits in it, and some even spent hours sorting through laundry detergent to get the small crystals they would later enjoy as a delicacy.

Former prisoner Qais Murad recalled being sent out of his cell to visit his folks on a summer day in 2013, but being pushed into a room as he was making his way there.

He walked inside and felt what felt like dirt on the ground. He saw guards throwing about ten bodies behind him while on his knees, his head bowed against the wall.

Murad recognised the substance when his cellmate’s socks and pockets were filled with salt when he returned from a visit later that day.

Murad told AFP, also in Gaziantep, “From that day on, we always made sure to wear socks, and trousers with pockets, for visits in case we found salt.”

The thrilled cellmates had eaten boiling potatoes that day with their first pinch of salt in years, unaware of its source, he recalled.

Murad remarked that The salt was all we cared about. Salt was priceless.