Ralph Schill, a professor at the University of Stuttgart’s Institute of Biomaterials and Biomolecular Systems, previously demonstrated that anhydrobiotic (dried) tardigrades could survive without absorbing water for many years.

It was previously unknown whether they age faster or slower in a frozen state, or if they age at all. But the mystery has been solved: tardigrades that have been frozen do not age. Schill explains that tardigrades do not die, but rather enter a deep sleep.

Tardigrades can withstand extreme heat and cold without harm. They show no signs of life, raising the question of what happens to the animals’ internal clocks and whether they age in this state of dormancy.

In a Grimm Brothers’ fairytale, the princess falls asleep. She is kissed by a prince one hundred years later, and when she awakens, she retains her youthful beauty. It is the same with dried tardigrades; thus, this is also known as the “Sleeping Beauty” hypothesis.

Schill said, “During inactive periods, the internal clock stops and only resumes running once the organism is reactivated. So, tardigrades, which usually only live for a few months without rest, can live for many years or even decades.”

It must have been ambiguous if this also implemented to frozen organisms. Schill and his colleagues investigated this by freezing more than 500 tardigrades at -30 °C, thawing them out, counting them, feeding them, and then freezing them again. This was done until all of the animals died.

The control groups were all kept at the same constant room temperature. When the time spent in the frozen state was excluded, the comparison with the control groups revealed an essentially equal lifespan.

Schill said, “So even in ice, tardigrades stop their internal clocks like Sleeping Beauty.”

Even when subjected to multiple cycles of freezing and thawing, the tough little animals live normal lives.

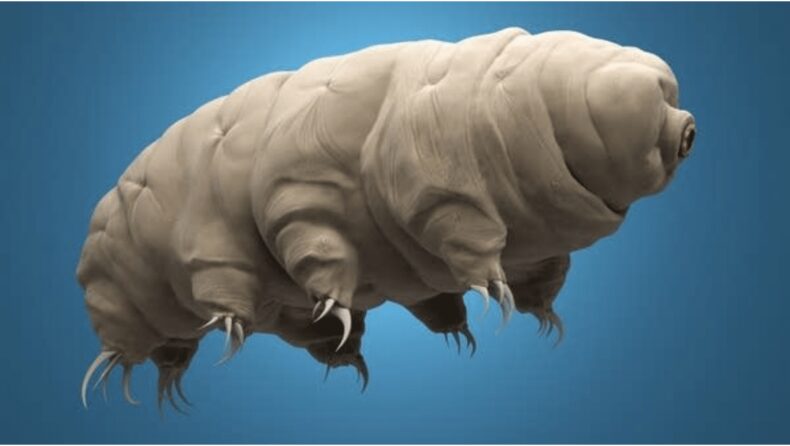

Tardigrades, also known as water bears or moss piglets, are a type of microscopic, moisture-loving animal that appears both adorable and alien. They are well-known for their ability to withstand drought and freezing temperatures by shutting down nearly all of their biological functions, achieving a state that is more extreme than mere hibernation.

Tardigrades are highly adaptable to harsh environmental conditions. Ralph Schill, a professor at the University of Stuttgart’s Institute of Biomaterials and Biomolecular Systems, demonstrated in 2019 that anhydrobiotic (dry) tardigrades can survive for many years without absorbing water.

It was previously unknown whether they age faster or slower in a frozen state, or whether ageing even stops. However, the mystery is now solved: frozen tardigrades do not age.

Tardigrades, also known as water bears, are members of the nematode family. Their gait is similar to that of a bear, but that is about it. The tardigrades, which are only one millimetre in size, have evolved to be perfectly adapted to rapidly changing environmental conditions, and can dry out in extreme heat and freeze in extreme cold.

Different types of stress are caused by freezing or drying out for a cell organism. Tardigrades, on the other hand, can withstand extreme heat and cold. They no longer exhibit any visible signs of life. This begs the question of what happens to the animals’ internal clocks and whether they age while at rest.

Ralph Schill and his colleagues addressed the issue of ageing in dried tardigrades, which spend many years in their habitat waiting for the next rain.

Schill and his colleagues investigated this by freezing more than 500 tardigrades at -30 °C, thawing them out, counting them, feeding them, and freezing them again.

This was done until all of the animals died. Simultaneously, control groups were kept at a constant room temperature. Excluding the time spent frozen, the comparison with the control groups revealed nearly identical lifetimes.