January 27 is observed as International Holocaust Remembrance Day to commemorate the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi German extermination camp where millions of Jews were killed. On this day of immense significance for public memory, the author shares what instances diplomacy has to remind itself of and what lessons it has to imbibe.

Table of Contents

What is the Commemorative Event?

The purpose of this day is to pay tribute to the memory of the victims of the Holocaust, and for the world to reiterate and reaffirm their standing unity to fight the evils of anti-semitism, racism and other forms of intolerance that can lead to violence that is targeted to certain groups or factions.

As UNESCO writes in a report, the Holocaust profoundly affected countries in which Nazi crimes were perpetrated, and which precipitated implications and consequences of an universal nature – spilling over to other parts of the world. The international community currently share a collective responsibility to address residues of trauma, create and maintain policies of remembrance, research and documentation of the Holocaust – and to remember perhaps the greatest and most impactful epilogue note the second world war left us with – ‘Never Again’.

In that order, Diplomacy and Foreign Policy has to imbibe some key lessons and insights, especially as the world faces the issue of a resurgence in far-right politics, a political and economic crisis, and a rise in hate-crimes, racism and Anti-Semitism.

Lessons for Diplomatic bureaucracy & Immigration Policy

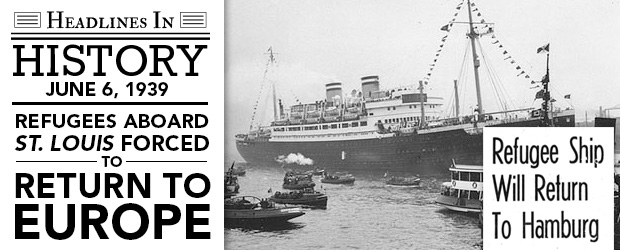

In May 1939, the German ship St. Louis sailed from Hamburg to Cuba – with 937 German Jews on board in hope of finding refuge. Cuba turned them away, and so did the US & Canada due to them not having proper immigration visas.

The ship was sent back to Europe, and the Jewish refugees were taken in by Western European nations. When Nazi Germany invaded much of Western Europe – many of these Jewish refugees were murdered in the Holocaust.

The St. Louis’ incident was termed a diplomatic disaster – it showed how governments all around the world set up strict and racist immigration quotas in the inter-war period – not understanding the humanitarian crisis that was going on in Germany.

As some experts believe, more than not understanding – they refused to do so, preferring a stance of inaction as long the Holocaust remained ‘domestic’.

Breckinridge Long, an assistant secretary at the State Department of the US, was one such diplomat, who refused to see the Holocaust as an atrocity of the gravest number – for him, it was all about maintaining immigration quotas.

He used his role in the immigration and refugee policy office to make it harder for Jews to be granted refuge in the US, as the Nazis continued exterminating them with machine precision.

Long established security checks, forged numbers and blocked crucial communication of the ongoing atrocities, in-order to keep Holocaust-fleeing Jew refugees to a minimum in the US.

Long had the official agency to help more and more of the ones who were being persecuted, but instead he and many other officials in the State Department went an extra mile to prevent the rescue of the Jews.

Finally the President of the US took action against this – but 4 million Jews had already perished by then. The report that brought the issue to President Roosevelt’s notice ended with the following warning,

“This government will have to share all time responsibility for this extermination.”

Often inaction is the loudest form of action. Diplomats all around the world indulged in similar instances of misuse of bureaucracy to create roadblocks for the European Jews who were fleeing persecution.

The rule-based order formed in the post-war world admitted these shortfalls, but work still has to be done in ridding the foreign policy bureaucracy of individuals such as Long, who can tilt the very ethical compass of the institution they represent, by simply restructuring diplomatic tools of dialogue, regulations and legal frameworks into justifications of inaction.

In such cases, personal bias – including elements of racism and anti-semitism, can poison the entire tank. As the world’s borders keep getting stricter, and the list of people fleeing persecution keeps increasing – governments need to root out such discriminatory elements.

On the contrary, there are many tales of diplomatic success from these periods as well – stories of diplomats stationed in Europe during the second world war to rescue vulnerable people from Nazi annihilation, often at great risks to their career and life. Diplomats should read about these brave accounts, alongside the deplorable acts of the likes of Long – to develop their own ethical compass for situations that might require unprecedented humanitarian action.

Such are the lessons that the horrors of the Holocaust provides current foreign policy practitioners – and their decisions, especially those pertaining to immigration and grant of refugees to those fleeing persecution, should be informed by these.

Dialogue should be used to facilitate humanitarian aid, not to evade it, legal frameworks should be used to protect, not restrict and regulation mechanisms should be to avert security threats, not to turn back those who have no home to go to.

Lessons to counter ‘Holocaust distortion’

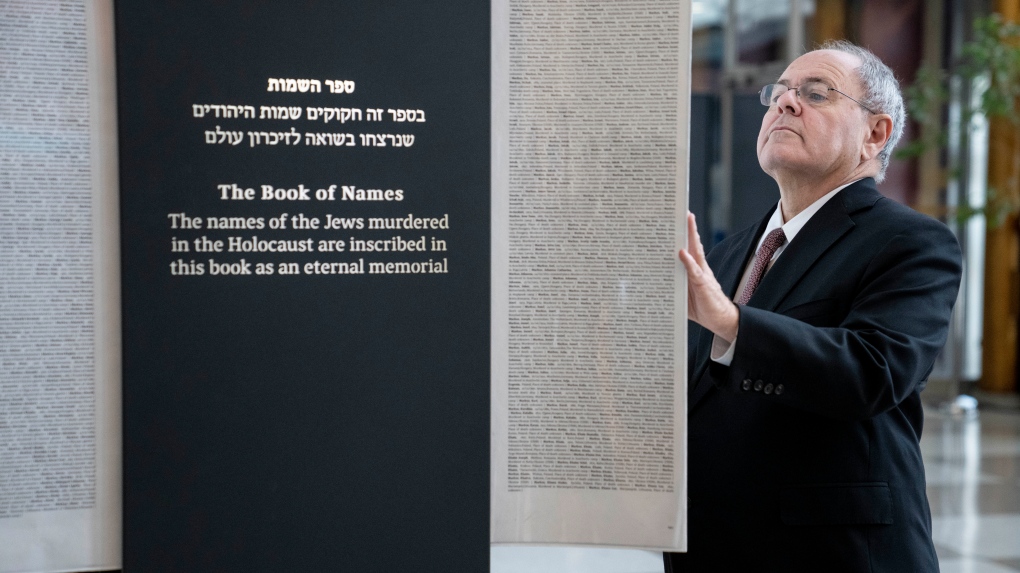

On Holocaust Remembrance Day, we have to also keep in mind -that we remember the Holocaust correctly. While the denial of the Holocaust has been observed for a long time, the threat of Holocaust distortion looms much larger.

According to the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance,

“Holocaust distortion acknowledges aspects of the Holocaust as factual. It nevertheless excuses, minimizes, or misrepresents the Holocaust in a variety of ways and through various media.”

When enough facts exist to prove the occurrence of the Holocaust, many actors choose to misrepresent these facts to create a distorted version of history. That creates a diplomatic challenge, as many regimes are relying on distortions of the Holocaust to make a history that is more usable for them.

The situation in Ukraine shows such an instance of Holocaust distortion. President Putin justified the invasion of Ukraine as a ‘Denazification’ move, while a top official in Moscow compared the Western support to Ukraine as a ‘final solution to the Russian question’, just like Hitler’s final solution to the Jewish question.

Countries like Austria have tried to defer their blame in the Holocaust by creating their own victim narrative.

Meanwhile, public protests have taken up signs from the Holocaust, most notably when anti-COVID vaccine protestors wore yellow stars of David on their clothes – by putting up the identification signs that Jews were made to wear, the protestors aimed to compare the inconvenience of not being allowed to enter a restaurant with being forced into a Ghetto and being deported and killed eventually.

These misinformed, and often purposely misdirected comparisons distort the horrors of the Holocaust, what it truly meant and the people who lost their lives in it.

In such a situation, diplomacy should be conducted mindfully. While dealing with a Holocaust denying, or distorting regime – a special emphasis on physical and human evidence should be used as tools of deliberation.

Diplomats also have to do their own part in preventing distorting Holocaust on their own. Drawing casual comparisons to the Holocaust, the Nazi war-machine or the Jewish experience can only further the distortion rhetoric, putting public memory of the Holocaust further at risk.

Countering Holocaust denial and distortion, especially through policy at the local and international level is important – because such distortion will only further perpetuate racism and anti-semitism, signal for violent extremism, and destabilize our current capability to draw actionable insights and lessons from the Holocaust.

The UN General Assembly passed a resolution to combat Holocaust denial and distortion last month, with this realization in mind.

Lessons to Identify & Avert Future Risks of Atrocities

We observe the Holocaust Remembrance Day with the haunting reminder, ‘Never Again’.

Humanity however, has been far from applying this lesson, as the post-war and contemporary period saw mass atrocities throughout the world, such as in Rwanda ( Tutsi Genocide). Kosovo (Serb Genocide), Sudan (Darfur Crisis), Myanmar (Rohingya Crisis) & China (Xinjiang Uyghur Crisis).

Genocide and other atrocious crimes against humanity, affect us all. Diplomats need to act on their capacity to remedy and counter the very possibility of such atrocities.

Generally, the international community believes that the only way to prevent genocide is by putting boots on the ground – either unilaterally, or through a multilateral forum, such as the UN. Interventions should be considered to be the final step, when all forms of diplomacy fail.

Interventions in the real world are very difficult to carry out, especially due the existing international system which views it as a risk and keeps it under strict compliance mechanisms – such as the requirement of a no-veto Security Council resolution. Interventions are also more legally complex to defend.

That is why, foreign policy usually follows the by-stander approach, standing aside with the hope that atrocities stop – and if it goes beyond a point, having to go in with a delayed, restricted and debated intervention.

To really stop such atrocities, a preventive approach should be adopted, especially since mass atrocities usually are carried out in a systematic manner, and those are the very links that need to be linked to predict a future risk.

Diplomats need to develop an ‘early-warning-system’ for identification of risks of possible mass atrocities and genocides, and lessons from inter-war Nazi Germany can present much of the basis for such a model.

A constant monitoring of states that are experiencing political, social and economic upheaval needs to be done – as far-right regimes tend to come to power in such ‘hospitable’ conditions. The analysis has to be then drawn to metrics such as the human rights index, press-freedom index, rule of law index, etc to identify whether the regime will walk the footsteps of a genocidal one.

While setting the Holocaust as a central point, experts suggest that the ‘industrial’ scale of the operation should not be the only comparing factor – that can lead to misidentification of a risky potential atrocity as a ‘no-risk’ one, just because it lacks systematic organization and precision of the Nazi extermination camps.

Tracking intent and ideology of a possible atrocity is far more important than its scale and factory-like organization, writes Pierre-Richard Prosper, Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues.

A situation such as the Uyghur crisis, when compared at face-value with the Holocaust, does not hold up. However when looked through the lens of a ‘permanent security’ angle, the risks flash up.

As Professor Anthony Dirk Moses, an authority on genocide, explains – The Jews were exterminated not only because they were scapegoated, The Nazis genuinely saw them and their numbers a threat for their future. The Nazis wished to build a 1000 year Reich, and therefore required permanent security.

In the case of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region in China, the Uyghur situation is one of permanent security. A large population of the Uyghur population is being incarcerated and put through a permanent re-education program, while by means of birth control – the birth rate of the community is controlled with the intention to diminish their numbers, and augment the Han population – so that the Uyghurs can never pose to be a security problem.

Tracing these breadcrumbs are far more important than trying to align the Uyghur crisis in direct line with the legal definition of a genocide.

Once adequate identification and evidence gathered, engagement is required through diplomatic and humanitarian action. States that pose risks of conducting atrocities should be subjected to bilateral appeal at first, and if that fails – should be put up for international condemnation through sanctions and embargoes.

A diplomatic course of action should be firm and clear about the consequences if compliance is not shown – in order to not be perceived as flaccid inaction.

Lessons For Soft-Power & Public-Diplomacy

On this important event, the world witnesses each year the collective power that something as abstract as memory can hold. This itself is a signal for foreign policy and its practitioners to gain soft-power insights, and integrate it greater into public-diplomacy initiatives.

The key lesson would be transparency. This article wrote an account on Long – the US diplomat who indirectly contributed to the Holocaust – from the archives of the US museum of Holocaust memory. That is because the US has embraced its fair share of blame in the horrific event, and decided to do everything in its capacity to never allow it to happen again.

Contribution to the Holocaust memory initiative, and admitting accountability in the Holocaust and issuing public apologies from Holocaust survivors are all instances of soft-power restructuring that many countries have undertaken in the recent past.

Public polls show that the approval rating of these governments, alongside the international perception towards them – both take a hike after such restructuring.

International arbitration initiatives, which help Holocaust survivors and victim families get remittances and compensations , also augment a state’s international perception. A country’s diaspora in a foreign country relies on their host country more, if that country has managed to secure and champion compensations for Holocaust survivors.

Finally, investing in Holocaust education – will act as a dual boon tide. Not only will a country’s public diplomacy wing get a significant boost – it would also ensure a new generation of global citizens, who will always remember to never forget.