The Solar Orbiter of the European Space Agency (ESA) may have made progress in the eighty-year-old puzzle of why the Sun’s outer atmosphere is so heated. One long known solution discovered by scientists was nanoflares, which are tiny heating bursts.

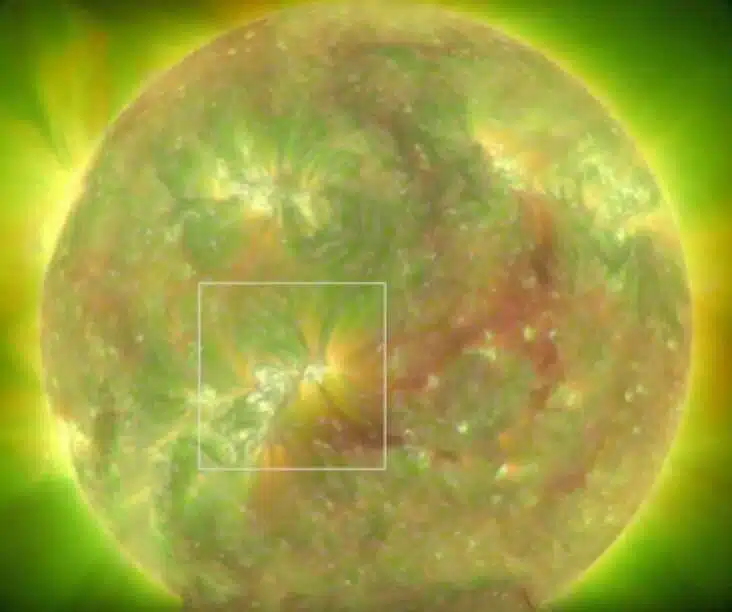

Several months into Solar Orbiter’s official mission, on March 3, 2022, the spacecraft’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) sent back data revealing for the first time that a magnetic process known as reconnection was occurring consistently on minuscule scales.

The spaceship was approximately halfway between the Earth and the Sun at that moment. This made it possible to synchronize observations with NASA’s Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) and Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) missions. The analysis then pooled the data from the three missions.

When a magnetic field transforms into a more stable configuration, magnetic reconnection happens. It is a key mechanism for energy release in superheated gases called plasmas and is thought to be the main source of energy for large-scale solar eruptions. This makes it the primary factor in the inexplicable heating of the Sun’s outer atmosphere and the primary cause of space weather.

The corona, the outer atmosphere of the Sun, is significantly hotter than the sun’s surface, as has been known since the 1940s. The corona is a rarefied gas at a temperature of around 2 million °C, while the surface burns at about 5 500 °C. Since then, it has remained a big mystery as to how the Sun generates energy to heat its environment to such a high temperature.

Magnetic reconnection has typically been observed in the past during massive, explosive occurrences. The current finding, however, offers incredibly fine-grained evidence of a persistent, 390 km across, small-scale reconnection in the corona. These are shown to be a long-lasting “gentle” sequence as opposed to the rapid explosive energy discharges that reconnection is typically known for.

The incident on March 3, 2022, lasted for a full hour. The null point, also known as the region where the magnetic field intensity is zero, sustained temperatures of about 10 million degrees Celsius and produced an outflow of material in the form of discrete ‘blobs’ that moved away from the null point at a speed of about 80 kilometers per second.

In addition to this ongoing outflow, a four-minute long explosive outburst also occurred right around this null point.

The findings of Solar Orbiter point to a continuous process of both mild and violent magnetic reconnection at scales that were previously too small to be determined. This is significant because it implies that reconnection can continuously transmit mass and energy to the corona above, warming it in the process.

These findings imply that smaller and more frequent magnetic reconnections may still be present. The objective now is to examine these in the future, around Solar Orbiter’s closest approaches, with EUI at even better spatio-temporal resolution in order to determine what portion of the corona’s heat may be transmitted in this manner.

The Solar Orbiter’s most recent near encounter with the Sun occurred on April 10, 2024. The spacecraft was only 29% of the distance from the Sun at that moment.International partners ESA and NASA are working together on the Solar Orbiter space mission, which is being run by ESA.

Read more on: https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Videos/2023/04/Tiny_magnetic_episodes_may_have_large_consequences_on_the_Sun