Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022 leaving a bloody trail behind them since then. However, the Russian war has not only impacted the lives and livelihood of the people of Ukraine but also caused massive damage to the entire Ukrainian cultural sector.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (guided by the principles of the Geneva Convention 1949) in 2017 stated that “attacking a country’s culture is to attack its humanity. Historic monuments, works of art, and archaeological sites- known as cultural property protected by the rules of war”

The Cultural War on Ukraine:

A month after the invasion, the effects could be seen, as workers desperately attempted to rescue the culture. In Lviv, at Andrey Sheptsky National Museum, the country’s largest art museum, staff struggled to move heavy elaborate pieces, and a giant piece of religious art, the 18th-century Bohorodchany iconostasis, to safety. The one-filled Museum of the History of Religion now saw empty cabinets, and sculptures were wrapped in foam and plastic to protect them from the threat of shrapnel at the Latin Cathedral.

Vladimir Putin implemented martial law in four Ukrainian areas that Russia had illegitimately acquired in October 2022.He also, explicitly legalized the looting of the country’s cultural heritage in the name of ‘preservation’ stated The Art Newspaper.

Unesco warns that war damages not only physical structures but also a nation’s intangible heritage and cultural industries. In 2022, the Ukrainian government stated that 37% of the country’s creative sectors lost their employment and 90% of creative businesses suffered significant turnover losses, according to Krista Pikkat, head of culture and emergency situations at Unesco.

Ukraine’s historical sites have sustained significant damage, according to Unesco (the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization). According to the Red List of Cultural Objects at Risk, around 259 cultural sites have experienced confirmed damage since the start of the war (excluding harm from the demolition of the Nova Kakhovka Dam, where a thorough assessment has not yet been done).

The terrible and lasting repercussions of this war on individuals like Yulia Danylevska, a young artist from Kherson in Ukraine, are not even remotely captured by cold statistics.

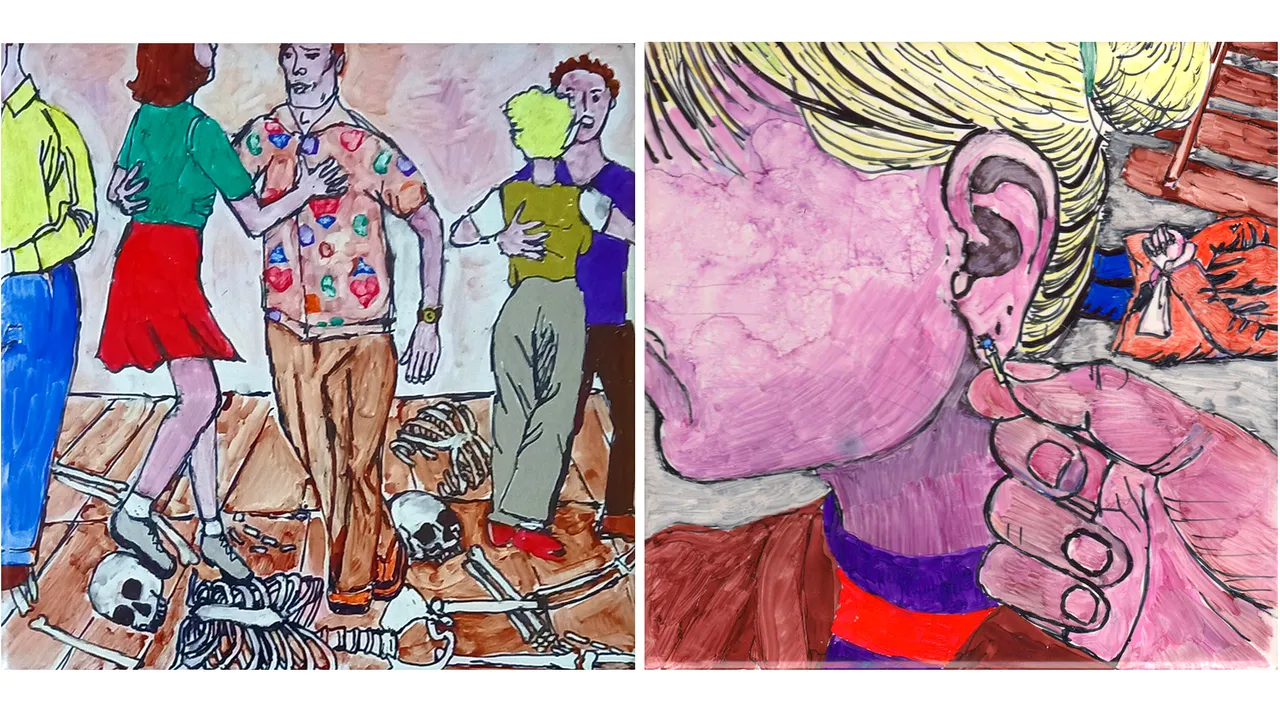

On white tiles, she has created drawings that reflect city life during the occupation using permanent marker pens. She depicts her viewpoints in rich, dramatic detail in her “stories” on tiles, which also include images of Mariupol, looters, a burning house, and other symbols of conflict. She wrote on Facebook, “I decided to show subtle moments that could remain unnoticed compared to the other crimes of the Russian army because I didn’t want to paint piles of corpses.” “The occupier’s hand removes a gold earring from the ear of a Ukrainian woman,” reads one of her pieces.

Another great artistic loss Ukraine suffered was the terms of loss of life’s work of the late artist Polina Rayko. She began painting at the age of 69 as a form to channelizing her grief on losing her husband, and her only daughter in a car crash. She decorated her entire home in Oleshky, in southern Ukraine, in the manner of fantasy folk art. It was a popular tourist destination and a national treasure.

However, in June, the enormous Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Station, which was situated in a Kherson area under Russian control, was demolished. It is believed that adjacent cities and villages, as well as Rayko’s home museum, were also flooded during the subsequent storm. The power plant itself was the only structure of its kind to be finished in the distinctly European-influenced Soviet monumental classicism style in 1954.

The Fight to Preserve:

Support for the fight to preserve Ukraine’s priceless culture is pouring in from all sides. London-based A nonprofit organization called Save the Spot hosts fundraisers. It has so far worked with 15 cultural organizations in Ukraine, including the Pokrovsk Historic Museum, the XII Months Zoo, and the Borodyanka Children’s Music School in the Donetsk region. Donors can assist the selected venue by contributing by buying “entrance tickets” to aid in their survival and eventual reconstruction.

At the Museum Crisis Center (MCC), a non-profit organization in Lviv, Bogdana Brylynska is a part of the monitoring team. It has been preserving cultural works ever since the crisis began, giving priority to small, regional museums in Eastern and Southern Ukraine, where fighting is most intense. Her statement is that “without help, the smaller institutions and their special collections risk damage or even total destruction.” How many cultural institutions are situated in occupied territory, according to her, is unknown. Even if they are far from the activity, museums are only trying to survive.

MCC offers financial and psychological support to cultural workers. “People feel that talking about their experiences in group therapy is really useful. It’s important to realize that you’re not alone, according to Brylynska. She also serves as the city’s literary festival’s director. She said, “Though last year we were without money, as all the funds went for the war.”

War on Culture; An Old Tactic

The destruction of a country’s cultural heritage in order to weaken its inhabitants has long been a tactic used in warfare. Examples from the present include the demolition of historical and religious sites in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan in 2001, and The Great Mosque of Aleppo in Syria in 2016.

In military law, cultural property protection (CPP) has a lengthy history. The Durham Ordinances of 1385, which were created for Richard II’s invasion of Scotland and contained a clause prohibiting harm to places of worship or other cultural institutions, are the first known code of discipline for an English army. Through the 1863 Lieber Code, which was created for Federal forces fighting in the American Civil War, the US is acknowledged as being the first nation to incorporate CPP into its military strategy.

The purposeful attack on cultural and religious sites that are not military targets or support military action is prohibited by international humanitarian law, the 1954 Hague Convention on the protection of cultural property in the event of armed conflict, and its second protocol drafted in 1999.