In the city of his birth, Kolkata, a famous Indian blind artist’s 44-foot-long Japanese-style handscroll has surfaced and is now being displayed in public for the first time.

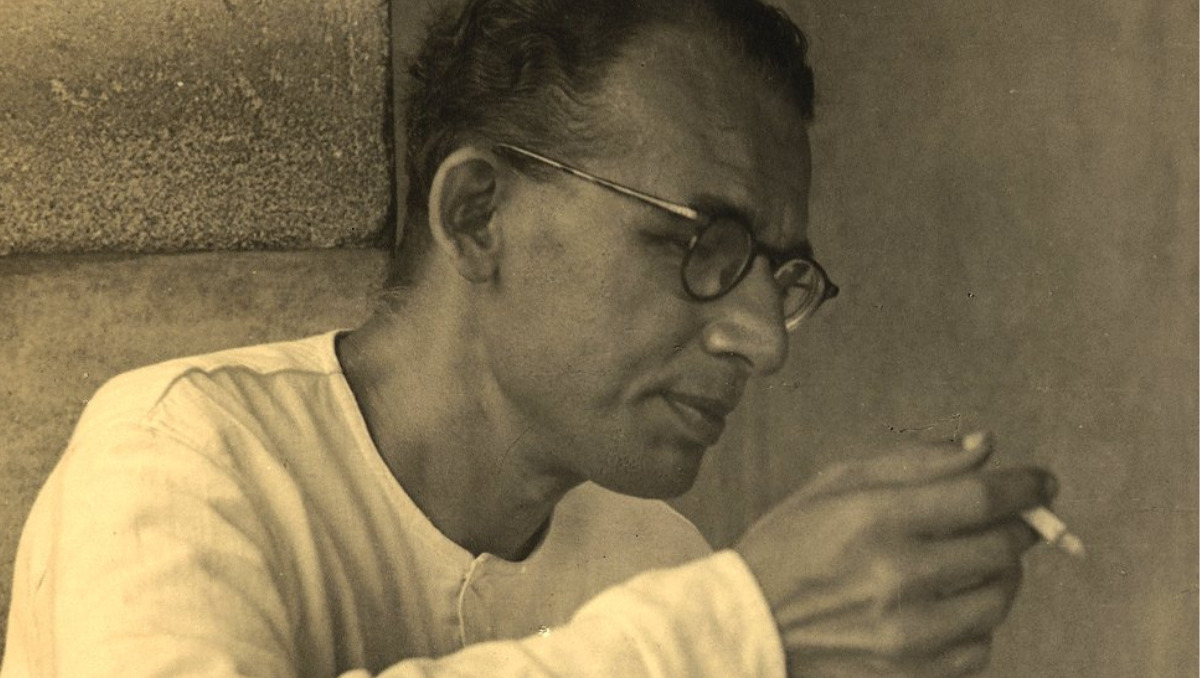

Benodebehari Mukherjee, who was born in 1904, was extremely myopic in one eye and blind in the other. At the age of 53, he was completely blind. Mukherjee, a landscape and fresco painter who passed away in 1980, produced ground-breaking works. He became known for defining modern art in 20th-century India. He was also a sculptor and muralist.

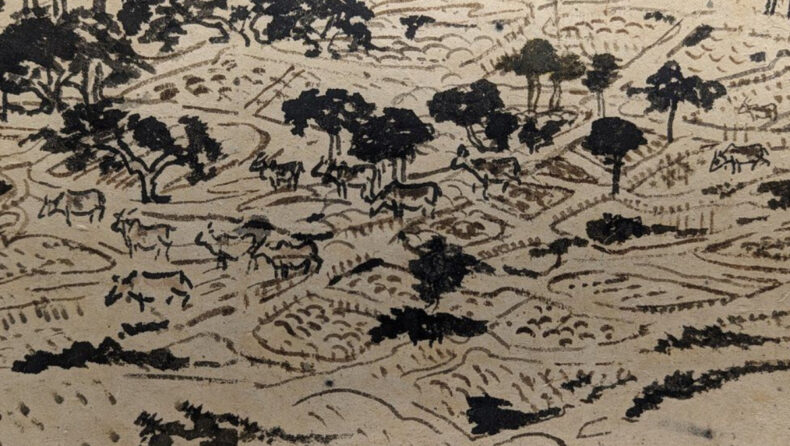

The scroll, which is only six inches broad, will be delivered in July to Santiniketan, the West Bengal university town established over a century ago by Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore, where Mukherjee studied and later taught. Scenes from Santiniketan is the title of the artist’s longest scroll.

The representation of the khoai, which was painted in the middle of the 1930s and is slightly over 10 feet long, was Mukherjee’s longest piece until it was discovered.

Before arriving at its final location in Kolkata, where it is currently on display, the scroll was transferred into two different hands.

It appears that in 1929, Mukherjee either gave the scroll to Sudhir Khastagir, a Santiniketan art school graduate, or sold it to him. Khastagir eventually relocated to Dehra Dun to work as an art teacher at a prestigious institution. He gave the scroll to another artist, who later sold it for an undisclosed sum to Rakesh Saini, an archivist and proprietor of an art gallery in Kolkata, six years ago.

Mukherjee created this intriguing scroll at the age of 20 using ink and watercolors on painstakingly arranged pieces of paper. The artist who leads the visitor on a tour of Santiniketan in the first frame is depicted as a figure sitting beneath a tree. This is a common pattern in Chinese and Japanese scrolls where carefully positioned figures direct our gaze.

There are 22 human figures, 22 cattle, 3 poultry, 1 dog, and 1 bird on the scroll. Mukherjee employs expanses of emptiness to represent the earth and the sky.

About Benodebehari Mukherjee

Known for what he brought to the realm of modern Indian art, Benodebehari Mukherjee (1904–1980) was a well-known Indian artist. In Behala, Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), West Bengal, India, on February 7, 1904, he was born.

At the Government College of Art and Craft in Kolkata, Mukherjee received a formal education in art. Abanindranath Tagore, a prominent artist and the founder of the Bengal School of Art, was his instructor and had a significant impact on him. Mukherjee’s early paintings were influenced by Bengal School aesthetics as well as indigenous Indian miniature painting techniques.

Later, Mukherjee experimented with many artistic genres and media, such as oil painting, watercolor paintings, and ink drawings. Additionally, he experimented with murals and sculptures. Mukherjee was renowned for his talent to express the essence of both the human form and nature in his artwork. His paintings frequently featured rural settings, village life, and legendary subjects.

Mukherjee‘s artistic career was put on hold when he was put in prison for his participation in the campaign for Indian independence from British domination. He continued to pursue his artistic endeavors after being freed, eventually enrolling in the Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, West Bengal, where he spent several years as an art instructor.

Mukherjee got the chance to collaborate closely with prominent artists like Nandalal Bose and Ramkinkar Baij during his time at Visva-Bharati University. Additionally, he got to talk to foreign scholars and artists that came to the university. His artistic horizons were expanded by these encounters, which also improved his creative process.

Extensive exhibitions of Mukherjee’s artwork were held both in India and overseas. He staged solo exhibitions in a number of places, such as Kolkata, Delhi, Mumbai, and London, and took part in a number of group shows. His work was praised by critics for its distinctive fusion of conventional Indian aesthetics with contemporary sensibilities.

Mukherjee was not only a recognised artist but also a recognised art teacher. He was a key contributor to the development of India’s art education curriculum and pedagogy. He encouraged his students to use art as a means of self-discovery by emphasizing the value of connecting it to nature and spirituality.

On December 11, 1980, Benodebehari Mukherjee passed away, leaving behind a lasting legacy in the field of Indian art. His works are conserved in numerous museums and private collections, and his efforts continue to motivate and influence future generations of artists. Mukherjee has become a significant character in the history of Indian culture thanks to his aesthetic vision and commitment to promote Indian art.

Students, scrolls and legacy

Mukherjee’s Kala Bhavan students were almost as well-known as his teachers. Artists like KG Subramanyan, Somnath Hore, and Oscar-winning

director Satyajit Ray was among them. The Inner Eye, a film by Ray about Mukherjee, was produced in 1972. The heartfelt tribute thrust the solitary artist and his creations onto the world scene.

Prints of handscrolls that Tagore and Bose had brought back from their trip to Japan may have served as an inspiration for Mukherjee.

Reproductions of Mukherjee’s other scrolls, such as The Khoai, Village Scenes, and Scenes in Jungle, are also on display during the Kolkata exhibition. The Victoria & Albert Museum in London is the owner of the final piece, which is painted on the semicircular pith of a banana tree.

The frescoes on the walls and ceilings of the structures in and around Kala Bhavan are among Mukherjee’s other well-known creations at Santiniketan. The Lives of Mediaeval Saints on the walls of Cheena Bhavan, a Sino-Indian cultural studies institution, are among the most well-known and stand at about eight feet tall and an impressive 80 feet in length. Before the artist lost his vision, he completed the frescos and scrolls.

Mukherjee continued to produce murals, collages, and sculpture to the end with the same artistic skill as the works he had produced when he could still see with that one eye, even after surgery removed his functional myopic eye.