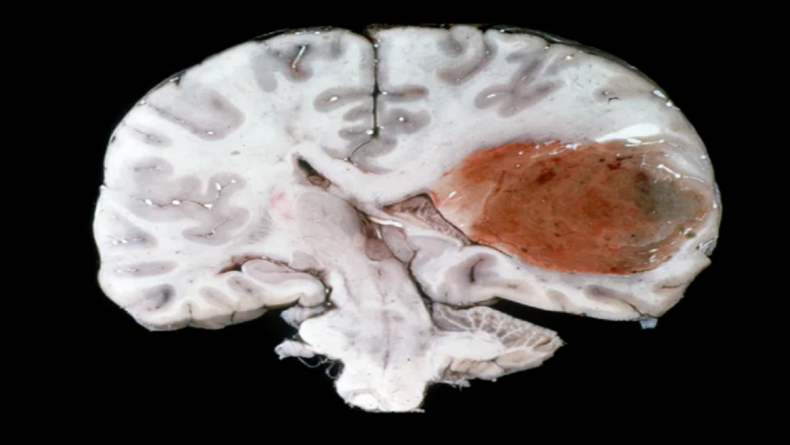

Researchers worldwide are looking for ways to curb invasive malignant brain tumours. Glioblastoma, an aggressive type of brain or spinal cord cancer that is the most difficult to resist because of its invasive nature, has been keeping scientists on their toes for years.

Recently, researchers from UT Southwest have discovered new properties of an existing medicine that has previously shown effectiveness in slowing tumour growth in certain animals. They have also found a biochemical pathway that might halt the spread of glioblastoma to adjacent brain tissues.

Why is glioblastoma so challenging to treat?

Glioblastoma patients have a survival time of just 15-18 months post-diagnosis. Tentacle-like projections from the central tumour reach the good brain tissues making it impossible to treat with either chemotherapy or surgery.

Scientists have been looking for ways to reduce the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EFGR), a protein that is the primary cause of glioblastoma. The EFGR protein is amplified in glioblastoma patients, which promotes the growth of cancer cells by sending unpredictable molecular signals. Several clinical trials have been conducted to reduce the EFGR in glioblastoma patients, but none have succeeded.

The new research

“We have identified a pathway that can suppress this cellular invasion, which could offer a new way to increase survival,” said Amyn Habib, M.D., Associate professor of Neurology, member of both the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center and Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute at UTSW and a staff physician at the Dallas VA Medical Center. Amyn and his associates conducted a study to demonstrate that when ligands are used to stimulate the cells with amplified EFGR, the receptor works as a tumour suppressor and limits the invasion of the cancer cells into healthy tissues. They gave some laboratory animals with glioblastoma tumours an FDA-approved arthritis drug called tofacitinib that increased the amount of EFGR ligands. They found that the tumours remained smaller and were less likely to invade the healthy brain tissues. These animals also survived longer than the animals which didn’t receive the drug.

The team of researchers will launch a human clinical trial in September to further elucidate the impact of tofacitinib. This new experiment could provide new methods to fight glioblastoma and renewed hope for patients living with this disease.