Kulbhushan Upmanyu, a Himachali agriculturist and a critical figure in the Chipko movement, has called for another mass movement in the state.

Table of Contents

“Himalaya Niti”

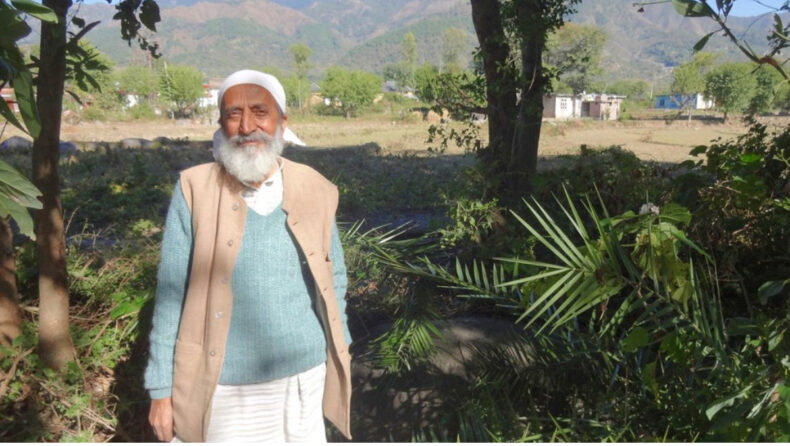

Way before his name would become gospel in Indian environmentalists circles, somewhere in the 1980s, Sunderlal Bahuguna was on a journey—the Kashmir-Kohima Chipko padayatra—to advocate for the protection of the Himalayan region. While history books and feature articles might have largely focused on Bahuguna, there was a man in his late thirties marching right beside him. Kulbushan Upmanyu, now 74, has voiced his desire to carry on his comrade’s work and advocate for the protection of his homeland, Himachal Pradesh, from nature’s wrath.

The wrath in question were the recent flash floods that smothered the state between July and September. Torrential downpour caused significant damage to human lives and property, with rivers swelling up and disrupting transport, communication and electrical lines. More than 400 people died in the span of those three months, with the government losing upwards of Rs. 12000 crore.

In a phone interview with the Indian Express, Upmanyu, who resides in the Chamba district of Himachal Pradesh as an agriculturist, expressed his devastation over all the innocent lives lost, adding that the impact wasn’t solely limited to Himachal. Not one to sit idle, he called for like-minded people to unite under a mass movement advocating for a development model that centred around the needs of the environment and delicate ecology of Himachal, i.e. “Himalaya Niti”.

What Upmanyu & Co. have been up to

Upmanyu had already established a platform in the form of Himalaya Niti Abhiyan in 2004, an organisation with a sole dedication to protect Himachal’s diversity and ecology. The recent developments had only strengthened his resolve in trying to convince the authorities of adopting “Himalaya Niti”, with his organisation seeing an uptick in activity.

He clarified, however, that the organisation didn’t completely shun development of any kind, but disapproved of the “unplanned, unscientific development” that caused great upheaval in the state in the past three months.

While they lack the status of a registered organisation, that hasn’t deterred support from thousands pouring in from Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and the North-east. Upmanyu has hailed the HNA as an open-platform where people itching to do something “for the mountains” can gather and translate that into action.

The organisation has been strongly demanding for the setting up of a task force with environmentalists and technical experts at the helm, along with a geological and tectonic study of Himachal Pradesh. It also demands for an inquiry commission, headed by a high court judge currently in office, that will attempt to figure out the causes of the recent disasters that have been widely attributed to negligence from the state. The HNA has also urged for a stricter enforcement of the recommendations given by the 2009 Avay Shukla Committee which advised against the construction of dams on mountains taller than 7000 metres from sea level.

Guman Singh, a trusted associate of Upmanyu and coordinator of the HNA, explained how the organisation also opposed the upgradation of the Kalka-Shimla highway and Manali-Kiratpur highway to four lanes, along with the construction of mega- and micro-hydro projects over the Satluj, Beas and Ravi rivers. He echoed Upmanyu’s philosophy by delineating that they wanted development with conservation, not one that brings destruction with itself.

He didn’t mince his words when he ominously declared that Himachal is “sitting on a disaster”, pointing to the long list of hydroelectric projects in the pipeline, planned to be built on volatile landscapes where strong winds are enough to cause acute erosion. To counter these worrying scenarios, Singh said that the organisation was switching to the methodology used by Sunderlal Bahuguna, who was present when the HNA was born.

Upmanyu expressed the same but with more romanticism, proclaiming that the time has arrived to “take forward the torch of Sunderlal Bahuguna”, and while he couldn’t be physically present after succumbing to COVID two years ago, his spirit would be more than happy to see Himachal Pradesh thrive despite being handicapped by natural disasters.

A flashback to the Chipko movement

Upmanyu recalled his times with Bahuguna, when he joined him on a protest march to push for the protection of Himachal Pradesh, the erstwhile state of Jammu & Kashmir, along with some areas of the Northeast in 1981. Then the agenda was to pressure the state government to stop the plantation of pine and eucalyptus trees on pasture and forest lands, with the government eventually giving in. Some 37 years down the line, the two would combine forces again, this time to protest against a ski village being built in Manali in 2018.

Upmanyu was struck by the white headscarf, or patka, that Bahuguna wore, and has adopted it in his own attire ever since. The white colour symbolised a peaceful resistance to Upmanyu, one that would also yield success.

Similar scenes of destruction wrought by floods in the 1970s beckoned Bahuguna and his wife, Vimla, to campaign three years later against corporate felling of trees which was leaving the hills of Uttarakhand vulnerable to massive soil erosion, and thus devastating landslides. Several hill people took a blood vow to protect the trees, displaying their intent by hugging them in order to deter lumberjacks. While the movement is generally regarded as a high point in Indian environmentalism, it has also been attributed as an “ecofeminist” event, considering that deforestation affected rural women the worst, who were tasked with collecting water, firewood and fodder.