Art is a medium through which one expresses their agency, their experiences, emotions or imagined narratives. In its most simple form, art can give us an insight into the image of oneself and of society.

While art does project a subjective understanding of a situation, that personal narrative in the larger scheme contributes to the identity of this artist by bridging the gap between imaginative expression and action.

Expressing one’s experience through visual language can illuminate ideas differently than one can with words. (Muhr, 2020)

Costumbrismo is a historical Latin American and Spanish form of art that represents the local customs, behaviours, and scenes of everyday life in the 18th and 19th centuries.

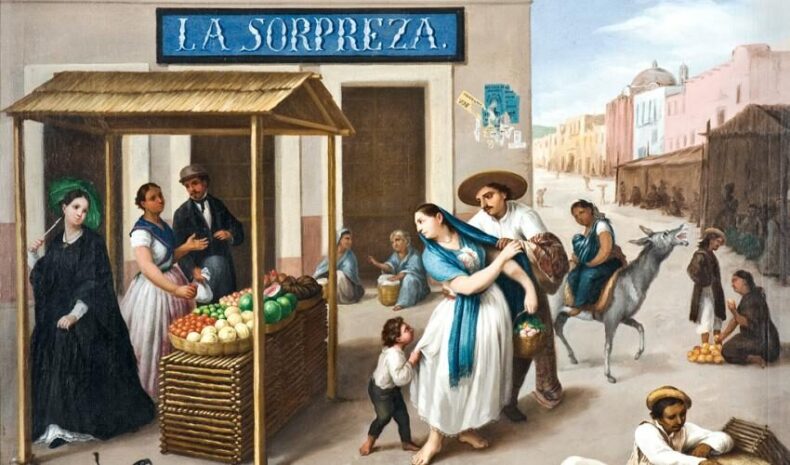

While meant to deliver a sense of local reality, this form of art captured a fictitious image of persons like street vendors, Mexican women like Las Poblanas (the women from Puebla) and imaginative market scenarios. Pictured in print, watercolours, writings and other forms of visual art, Costumbrismo articles were shared widely to influence the vision of Latin America outside and the formation of a feeling of national identity at home.

Costumbrismo, derived from the Spanish word for customs, explores everyday life in forms of art.

Sometimes, the portrayal of traditions exists not in an accurate representation but in an idealistic view of their communities. For example, Carl Nebel, a German artist who travelled to Mexico in the 19th century released a publication called ‘Picturesque and Archeological Voyage in the Most Interesting Part of Mexico’.

In this publication, his portrayal of the locals based on their clothing and the lack of architectural detailing assists us in interpreting the importance given to garments as an emblem of community identity. Unlike the present, clothing was not a statement of style but an expression of occupation, gender, age, marital/racial/social status as well as nationality. One can also develop the reflection of the locals and their image shared by potential travellers and tourists across the globe.

Identities through Costumbrismo

According to the identity development theory in psychology, identity is formed by a process of evaluating alternatives and selecting one depending on the results of their evaluation, thus forming the agency of an individual in their choices.

Further, Dewey in his book “Art as experience” defines art as that which cannot be separated from experiences in daily life and simply be seen as a pleasing mechanism. He states “Because experience is the fulfilment of an organism in its struggles and achievements in a world of things, it is art in germ. Even in its rudimentary forms, it contains the promise of that delightful perception which is esthetic experience.” (Dewey, 1934)

Since art is created from and reflects everyday experience, it also serves as a reflection of the artist’s community. This allows the artist to express himself via his work. With this understanding of art, both the identity of the independent artist and the community may be created and preserved at the same time.

As far as one considers identity formation to be a result of the interactions between daily experiences and those experiences to be expressed via art, a direct correlation is established between identities and art.

Costumbrismo came to be known not just as a form but as a movement in visual and literary art that sought to represent late eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century Mexico. Post-independent Mexican Costumbrista Artists used this movement to celebrate an elitist view of Mexican culture and art, to project an image to other nations as well as imbibe that image nationally.

The literary works and visual art of the Mexican Costumbristas were part of a wider, worldwide debate on nationalism and national identity.

A dichotomy between the norm and the difference is at the heart of Costumbrista‘s creative expression. Costumbrista artists and writers attempted to formulate a national identity based on notions of similarity to, and difference from, European nations.

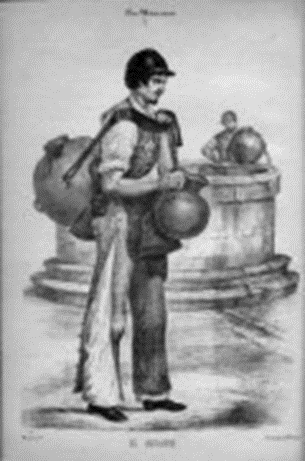

These rejections of the European culture as well as of traditional values that acted as a constraint to growth are expressed in Costumbrista art. I will take the example of ‘El aguador’ as represented in two albums, Los Mexicanos (Mexican) and Los españoles pintados por sí mismos (Spanish).

Although the two characters represent the same profession, their outfits and attitudes set them apart. I chose this example because the text accompanying the sketches reflects the difference in the emphasis on a Mexican character of lower birth.

The text by Abenamar in the Spanish album focuses on the hardships and poverty of the water carrier. In the Mexican version, Hilarión Fras y Soto, on the other hand, recalls various talks between him and the aguador who is bringing water to his house.

“Come here Trinidad,” the author yells as the aguador approaches softly. “Take a seat in this chair and describe your way of life to me.” The aguador blatantly queries why someone of the author’s standing and social class would be interested in learning about his life. “Imagine son, nowadays we Mexicans are painting ourselves, do you understand?” the author replies.

In writing about their own people, the Mexican authors assume a sense of pride and ownership, which is explicitly expressed in this discourse. The idea of being characterised by wandering artists and writers was no longer acceptable. In this light, Mexican Costumbrista artists were critical of the ‘exotic and sensual’ depiction of Mexican women by foreign artists like Carl Nebel.

| |

As stated by Benedict Anderson, nations were imagined to exist via the portal of print capitalism.

Costumbrista artists were deciding what was significant to Mexican identity and the country as a whole in their depictions of their environment and their citizens, and it was through Costumbrista magazines and newspapers that ideas and images of what made up being a Mexican were constructed and disseminated.

“It was through Costumbrista albums like Los Mexicanos pintados por sí mismos that racial and social popular types were conceived and disseminated, and notions of modern Mexican identity were formulated.” (Moriuchi, 2013)

Costumbrismo as an expression of experiences and of local customs brings together both arguments in order for us to comprehend how this particular art form, when analyzed, gives us an insight into the being of both – the subjects and the artists.

Read more: art and culture.

- Muhr, M.,(2020) Beyond words – the potential of arts-based research on human-nature connectedness. M. Ecosystems & People., (16)1, 249-257

- Mernick, A. (2021). Critical arts pedagogy: Nurturing critical consciousness and self-actualization through art education. Art Education, 74(5), 19-24.

- Dewey, John.(1934) Art as Experience (New York: Capricorn books, 1934)

- El Aguador. Lithograph. From Los Mexicanos pintados pos si mismos : tipos y costumbres nacionales, pos varios autores (Mexico City: Manuel Porrua, S.A. 1974)