For their work on quantum information science, a “completely insane” field with enormous implications, notably in the realm of encryption, three scientists shared this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics on Tuesday.

The “completely wacky” discipline of quantum information science, which has important applications notably in the realm of encryption, was jointly awarded this year’s Nobel Prize in physics on Tuesday by three scientists.

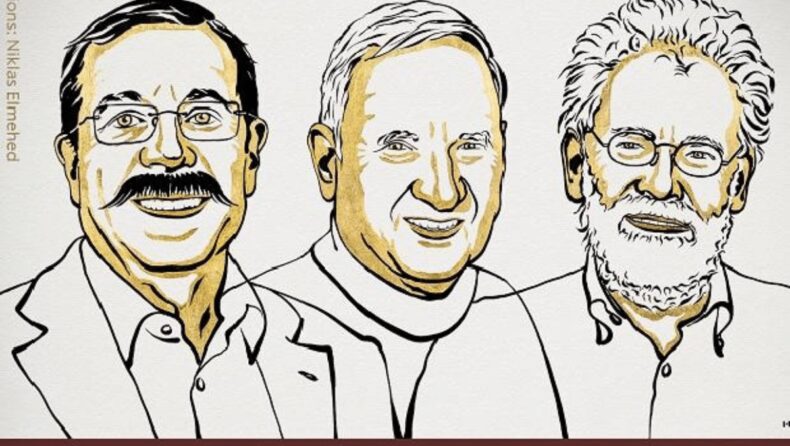

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences recognized Frenchman Alain Aspect, American John F. Clauser, and Austrian Anton Zeilinger for their work in understanding how invisible particles, such as photons, can be linked or “entangled” with one another despite being separated by great distances, a field that even alarmed Albert Einstein, who once described it in a letter as “spooky action at a distance.”

Two objects cannot occupy the same space at the same time, according to classical physics. This was thought to be a fundamental physics law that everything of nature obeyed until the early 20th century.

But as time went on, researchers started looking at subatomic particles like atoms, electrons, and light waves, which didn’t seem to follow these rules. In an effort to better understand the “quirky” laws that did connect these particles, Max Planck, Neils Bohr, and Albert Einstein founded the subject of quantum mechanics.

Everything stems from an aspect of the world that even Albert Einstein found puzzling and connects matter and light in a convoluted, chaotic manner.

There is a connection or relationship between pieces of matter or information that were once close by but are now apart; this relationship or connection may be exploited to teleport or encrypt data.

This is recently demonstrated by a Chinese satellite, and quantum computers, which are still in their infancy and are not yet very practical, might operate at lightening speeds. Some people even want to incorporate it into superconducting material.

Aspect described his involvement in a phone conference with the Nobel committee as “very strange.” “I am embracing in my mind something that is completely insane.” However, the trio’s experiments revealed it occurs in reality.

Several hours after receiving the formal call from the Swedish Academy informing him of his honor, Clauser told The Associated Press during a Zoom interview, “Why this happens I haven’t the foggiest.” “Entanglement appears to be extremely real, but I have no idea how it works.”

His other winners concurred that they are unable to explain the how or why of this phenomenon. However, they conducted increasingly complex experiments to support their claims.

Clauser, 79, received his medal for an experiment he conducted in 1972 using salvaged materials that assisted in resolving a historic argument between Albert Einstein and eminent physicist Niels Bohr over quantum mechanics. According to Einstein, there is “a spooky action at a distance” that will someday be proven false.

Clauser admitted, “I was betting on Einstein. However, I was mistaken, Einstein was mistaken, and Bohr was correct.

Although technically incorrect, Einstein, according to this aspect, deserves enormous credit for posing the pertinent query that resulted in tests demonstrating quantum entanglement.

Most people believe that nature is composed of materials dispersed throughout space and time, according to Clauser, who created a video game on a vacuum tube computer in the 1950s while still a high school student. And it doesn’t seem to be the case.

According to Johns Hopkins physicist N. Peter Armitage, the research demonstrates that “pieces of the universe — even those at tremendous distances from one another — are related.” This is so counterintuitive and goes against everything we believe the world “should” be.

Beginning Monday, a series of Nobel Prize announcements saw Swedish scientist Svante Paabo get the prize in medicine for discovering Neanderthal DNA’s hidden information that was crucial to understanding our immune system.

Wednesday is chemistry, and Thursday is literature. The Nobel Prize in Economics will be awarded on October 10 and the Nobel Prize in Peace on Friday.

The cash awards for the prizes total 10 million Swedish kronor, or roughly $900,000. They will be distributed on December 10. The funds come from a bequest made by Alfred Nobel, a Swedish inventor of dynamite who established the award in 1895.

The reports came from Berlin-based Jordans, Kensington, Maryland-based Borenstein, and New York-based Burakoff. Contributors were David Keyton in Stockholm and Masha Macpherson in Palaiseau, France.