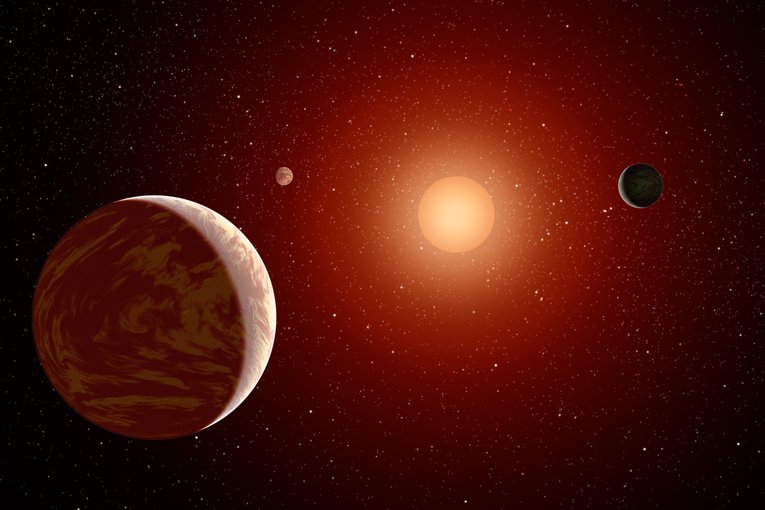

New research on M Dwarf Star proves to be disappointing for fostering potential life on other planets

Life harbouring planets facing a dramatic drop, according to scientists. The most common type of star in our universe, star M dwarf, was studied to provide a suitable environment for life sustenance for nearby planets as they are rich with carbon.

However, recent studies prove a disappointing halt to that hope: researchers in a new study of a world that orbited an M dwarf star, existing about 66 light-years away from earth Earth, found no indication that such planets could hold onto a livable atmosphere at all. Without the existence of carbon, the epicentre of all living things, a planet will not be a hospitable arena for the growth of life. These stars are also commonly known to be volatile and spit solar flares and radiation on neighbouring celestial bodies like planets.

However, large planets orbiting these M Dwarf stars were expected to survive the intensity and thrive in the “Goldilocks Environment”; where the planets are close enough to the small star to keep warm, yet large enough to attach themselves to its environment. A recent study proves otherwise, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, where its shows that the nearby M dwarf star’s presence could be too intense for a habitable environment

Earth’s environment is also privy to a similar phenomenon, where the nearest and the biggest star in our solar system, the sun, deteriorates the atmosphere our planet exists in due to regular solar flares. In spite of that, Earth remains largely unscathed due to the large levels of volcanic and other gaseous activity to replace the atmospheric loss the sun causes and makes it mostly undetectable.

These findings also do not bode particularly well for the planets that orbit the M Dwarf Star says Michelle Hill, the co-author of the study, a planetary scientist and a doctoral candidate at the University of California, Riverside. She says in a post on UC’s website: “The pressure from the star’s radiation is immense, enough to blow a planet’s atmosphere away,”

The GJ1252b M Dwarf Planet studied in the research is said to have “700 times more carbon than Earth” but is still reported not to have an atmosphere. This star orbits reportedly less than a million miles from its home star, titled GJ_1252. The planet’s existence was first discovered by NASA’s (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite mission)

The then 17-year-old Spitzer Space Telescope was ordered to be used to analyse the area back in January 2020 and was deactivated less than 10 days later. The investigation was led by Ian Crossfield, an astronomer from the University of Kansas and a collection of researchers from UC Riverside, The University of Maryland, the Carnegie Institution for Science, the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, McGill University, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech, The University of New Mexico and the University of Montreal.

The data provided by Spitzer was analysed and searched for potential emission signatures or signs that a ‘gaseous bubble could encase the planet” The telescope captured the planet passing its home star, allowing researchers to “look at the starlight as it’s passing through the atmosphere of the planet,” giving a “spectral signature of the atmosphere” — or lack thereof, Hill said.

She added that the observation of the lack of an atmosphere wasn’t shocking, yet disappointing

Hill continues to look for moons and planets categorized into ‘habitable zones’ but the results following this discovery makes planets orbiting M Dwarf Stars less interesting

With the aid of the James Webb Space Telescope, the most powerful space telescope to date, scientists anticipate learning much more specifically about these kinds of planets.

The TRAPPIST-1 system, which also contains an M Dwarf star with a number of rocky planets surrounding it will be the next target for Webb, according to Hill.

“There’s a lot of hope that it will be able to tell us whether those planets have an atmosphere around them or not,” she added.

“I guess the M dwarf enthusiasts are probably holding their breath right now to see whether we can tell whether there’s an atmosphere around those planets.”

However, there are still multiple areas of interest in the hunt for habitable worlds.

There are still around 1,000 sunlike stars that exist very close to Earth that have their own planets circling inside habitable zones, according to the UC Riverside’s post on the findings, except that planets farther away from M dwarfs may be more likely to sustain an atmosphere.