After Vanuatu won a historic U.N. vote after a four-year campaign, the world’s top court, the ICJ, can now specify obligations and consequences countries must follow to reduce global warming.

Table of Contents

Vanuatu, a nation of Pacific Islands, won a historic vote at the U.N. General Assembly on Wednesday, asking the world’s highest court to define the duties countries have to address the climate crisis and the repercussions if they don’t.

The campaign, led by the Republic of Vanuatu and inspired by Pacific Island law students, lasted four years. Finally, the historic motion asking the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion was approved unanimously.

There was no request for a vote from any of the 193 member states approving the proposal by consensus. Moreover, applause broke out in the General Assembly Hall when the resolution passed. The legal obligation of ICJ could also inspire nations to take more decisive action and define international law.

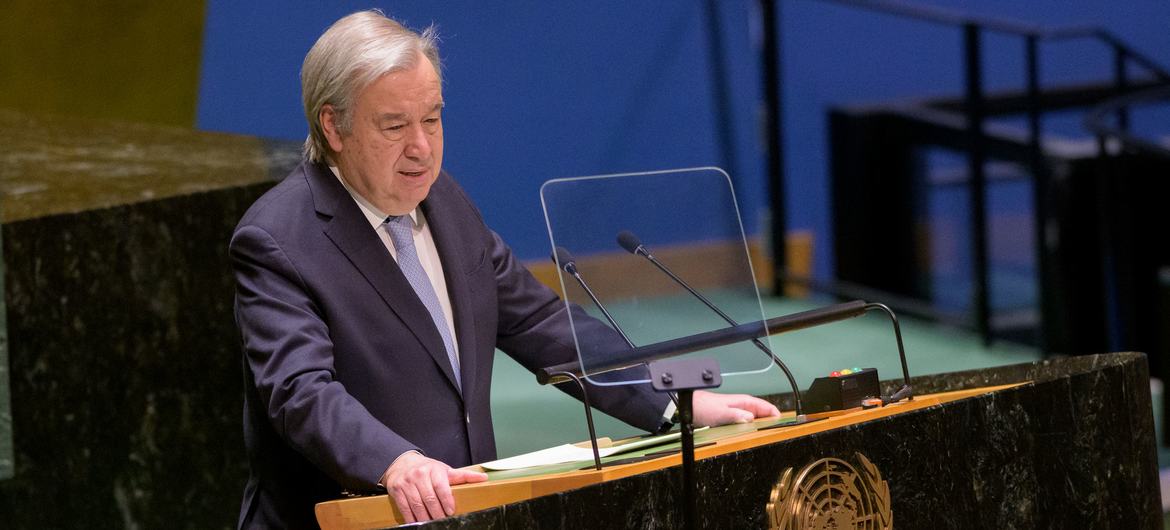

The action “would allow the General Assembly, the U.N. and member states to take a stronger approach towards climate action that our world so desperately needs,” said António Guterres, the U.N. secretary-general.

An incredible feat achieved by the Republic of Vanuatu

A small country in the Pacific Islands finally achieved an incredible diplomatic victory. With a population of 300,000, Vanuatu brought together nations to petition the world’s top court for advice on a crucial issue: Can countries be held liable under international law for failing to halt or reduce climate change?

It began calling for the ICJ to issue an “advisory opinion” on the legal obligation of governments to address the climate catastrophe in 2021, claiming that Pacific Islanders’ human rights have been violated by climate change.

Ishmael Kalsakau, the prime minister of Vanuatu, declared shortly after the resolution’s passage that “today we have witnessed a win for climate justice of epic proportions.” He added that Vanuatu, a tiny Pacific island nation, successfully led such a transformative outcome, which “speaks to the incredible support from around the globe,” he added.

Challenging yet necessary resolution for Pacific Islands

Vanuatu and other vulnerable nations are already dealing with significant effects of climate change. For example, climate-related hurricanes have wreaked havoc on the nation of islands in the south Pacific, including two category-four storms this month that forced 10% of its citizens to remain in shelters.

The movement to request an advisory opinion from the supreme court of the globe started in a Fijian environmental law class in 2019. The International Court of Justice was the solution chosen to use to address the climate crisis head-on through different international legal channels, according to Cynthia Houniuhi, president of Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change.

Cynthia Houniuhi said they are overwhelmed that the world has finally decided to act on the idea that “started in a classroom four years ago.” Four years after they proposed an ICJ resolution to Vanuatu officials, these students’ efforts brought success on Wednesday, and they celebrated the vote.

What does the new U.N. resolution mean?

The nations are consulting the International Court of Justice concerning whether or not governments have “legal obligations” to protect citizens from climate hazards and, more importantly, whether or not failing to comply with those obligations could have “legal consequences.”

The opinion of the ICJ would not be binding on nations. Still, depending on what it says, it could transform the voluntary commitments that every country has made under the Paris climate agreement into legal obligations under various existing international statutes. For example, it will include those on the rights of children or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which could then lay the groundwork for new legal claims.

It could take the court up to 18 months to issue an advisory opinion, which could help countries clarify their financial obligations related to climate change, improve the national climate plans they submitted to the Paris Agreement, and strengthen domestic policies and legislation.