The Citizenship Amendment Act applications were considered by the Supreme Court on October 31, 2022, and it was determined to hear a particular batch of petitions on December 9, 2022, while ordering two nodal counsels to gather pertinent case-related materials.

Uday Umesh Lalit, the Chief Justice of India, presided over the bench, which also included S Ravindra Bhat and Bela M Trivedi. The All Assam Student Union (AASU) and other individuals opposed to the CAA filed the petition. The panel designated Attorney Pallavi Gupta to represent the petitioner Indian Union Muslim League and Attorney Kanu Agrawal as nodal counsel to gather the pertinent case documentation.

The Citizenship Amendment Act is what, exactly?

For the minority community who experienced religious discrimination in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan, it is a quick route to obtain citizenship. Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, Buddhists, Christians, and Parsis are six of these minorities. The Act does not include Muslims or Muslim sects like Shias and Ahmedis, who are equally persecuted in Pakistan. This is the contentious portion. The cost of migrants’ costs will be borne by the entire nation, and they are free to live anywhere in the country.

The Lok Sabha passed the Bill earlier in 2016, and it was abandoned in 2019. On December 11, 2019, Parliament approved it, and it went into force on January 10, 2020.

Citizenship status at the moment

The Citizenship Act of 1955, which established citizenship by naturalisation, will be amended by the Citizenship Amendment Act of 2019. It implies that someone who has resided in India for the last 12 months or 11 of the previous 14 years may become a citizen.

If the applicant’s parents or grandparents were Indian citizens, they could also become citizens of India. Thanks to the Amendment, people can now naturalise and obtain citizenship in 5 years.

The Act also included a provision to terminate the registration of Indian Overseas Citizens (OCI). The sixth basis, which is added, is a violation of the Citizenship Act. The other five grounds—fraudulent registration, disrespecting the constitution, siding with the enemy during hostilities, or any action that adversely affects sovereignty, security, or the public interest—are already present.

The CAA gives cardholders advantages by granting them the freedom to visit, work, and study in India. People with OCI cards are foreigners who are either of Indian descent themselves or through their wives.

In accordance with the Citizenship Act of 1955, an illegal immigrant is one who enters the nation using forged documents, lacks a passport that is now valid or stays longer than is permitted by their visa.

According to the Citizenship Amendment Act, immigrants who practise one of the six aforementioned religions will now be treated as citizens of India from the moment they enter the nation, and all legal actions taken in opposition to their illegal entry and stay will be dropped. People who entered India on or before December 31, 2014, are subject to this.

Exceptions Under Citizenship Amendment Act

Certain regions of the nation are exempt from these rules under the Act. North-Eastern States are included in this. It would not apply to the tribal regions of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Tripura, which are listed in the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

These regions include Tripura Tribal Area District, Garo Hills, Chakma District, and Karbi Anglong (Assam). The Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873 does not apply to the territories inside the Inner Permit Line. (Visitation is governed in Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, and Mizoram by the Inner Permit Line.)

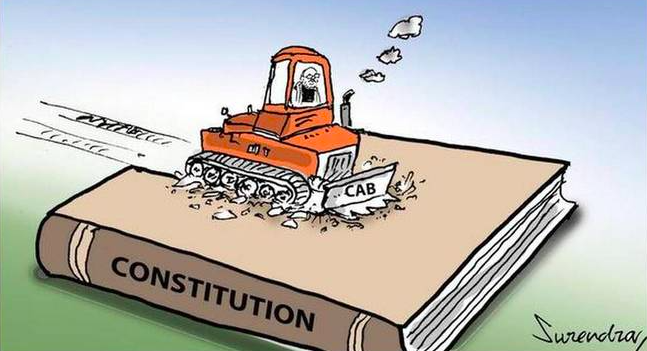

Why is the Act under fire?

The violation of Article 14 of the Indian Constitution, which grants both citizens and visitors to the nation equal status, is one of the most significant reasons why the Act has drawn criticism. And there will be exceptions to this rule based on good reason.

The CAA deviates from Article 14 by treating illegal immigrants differently based on four factors:

a. country of origin;

b. religion;

c. date of entry into the nation; and

d. place of residence.

For this reason, the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML), MP Mahua Mitra, AIMIM leader Asaduddin Owaisi, NGO Rihai Manch, Assam Advocates Association, and other organisations and individuals have filed more than 200 cases before the Supreme Court against the CAA.

Due to frequent migration from India to the three specified nations—Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh—the Act exclusively permits illegal immigrants from these three countries. Minorities face persecution in these nations because they have made their state religion official.

Nevertheless, people have relocated to Bangladesh and Pakistan. Afghanistan’s position on the list, however, is debatable because no one has relocated there.

The Act mentions religious minorities, thus it is puzzling why only these 3 nearby nations were listed. Why then not other nations like Sri Lanka, where Tamil Eelams suffer discrimination due to Buddhism being their official religion?

A Similar situation exists in Myanmar, where Buddhists predominate and the Rohingya Muslims are persecuted. These Minorities frequently seek safety in India. The exclusion of all Ahmadiyya Muslims in Pakistan—who are regarded as non-Muslims—is a religious community that also faces persecution.

The Act is also ambiguous about immigration to the North-Eastern States and those individuals who are currently residing there illegally. As a result, there were numerous protests, with Guwahati serving as their focal point.

They worry that the CAA will alter the language and culture of the states as well as their demographic makeup. Additionally, they are demonstrating against Bangladeshi illegal immigration.

Another justification for the demonstration is that citizenship in India can be obtained through birth, descent, naturalisation, or acquisition. However, the CAA is altering this dynamic by enabling citizenship based on one’s faith, which is against secularism (the idea that all religions are equal in the eyes of the State), which is a component of the Indian Constitution’s Basic Structure.

The Indian government is submitting an affidavit to the Supreme Court in which it claims that CAA is assisting individuals in need and is a kind act toward the populace and does not conflict with the nation’s democratic, secular, and sovereign nature.

All eyes are now on the Supreme Court to decide how it will rule on all of the petition batches.